Add your feed to SetSticker.com! Promote your sites and attract more customers. It costs only 100 EUROS per YEAR.

Pleasant surprises on every page! Discover new articles, displayed randomly throughout the site. Interesting content, always a click away

Dovetail Cultural Resource Group, A Mead & Hunt COmpany

Knowing the Past -- Building the FutureUncovering African American Lives in Civil War Records 1 Apr 2025, 5:26 pm

Figure 1: A U.S. Army impressment labor roll for enslaved workers at Camp Nelson, a military base in central Kentucky (NARA 1864).

By Cameron Boutin

The Civil War is an extensively documented conflict, with a wide range of reports, letters, diaries, and other records chronicling the big and small events. But the vast majority of these materials were written by white Americans—the voices of African Americans are much more limited, and those of people who were enslaved are even rarer. In U.S. history in general, generations of enslaved African Americans lived, worked, and died throughout the country with hardly any written record of their existence other than a bill of sale or note in a plantation account ledger. As a result, those wishing to learn more about the lives of enslaved people need to utilize various sources to try to piece together their stories. This is especially true during the Civil War years. In particular, one aspect of the enslaved experience during the wartime period that has received little attention is the military impressment of enslaved laborers.

Impressment was the policy of the U.S. and Confederate armies to seize food, animals, and other resources, including enslaved people, to support their operations in the field during the conflict. Enslaved people were forced to perform labor for the military, including building fortifications around key Confederate cities like Richmond and Petersburg in Virginia, and constructing roads to help move U.S. troops and supplies in Kentucky. Even after the U.S. government issued the Emancipation Proclamation—freeing enslaved individuals in Confederate territory—and began recruiting African Americans as soldiers, many enslaved people in Border States like Kentucky continued to be exploited by Federal forces. Both the U.S. and Confederate militaries paid for the impressed labor, but they provided the wages to the white slaveholders rather than the Black workers, who were also not given freedom for their service to the respective war efforts.

Few, if any, impressed African Americans left written accounts of their experiences as impressed laborers, but the documentation produced by the military to keep track of these individuals and the money owed to their slaveholders offer a wealth of information to present-day researchers. These impressment labor rolls recorded enslaved people’s names, perhaps for the first time in their lives. The records also generally listed their periods of service and the area of the country where they worked, along with the amount of compensation awarded to each enslaver (Figure 1). The impressment rolls provide a glimpse into enslaved peoples’ wartime experiences but taking that information and examining other types of governmental records can reveal more about their lives before, during, and after the Civil War.

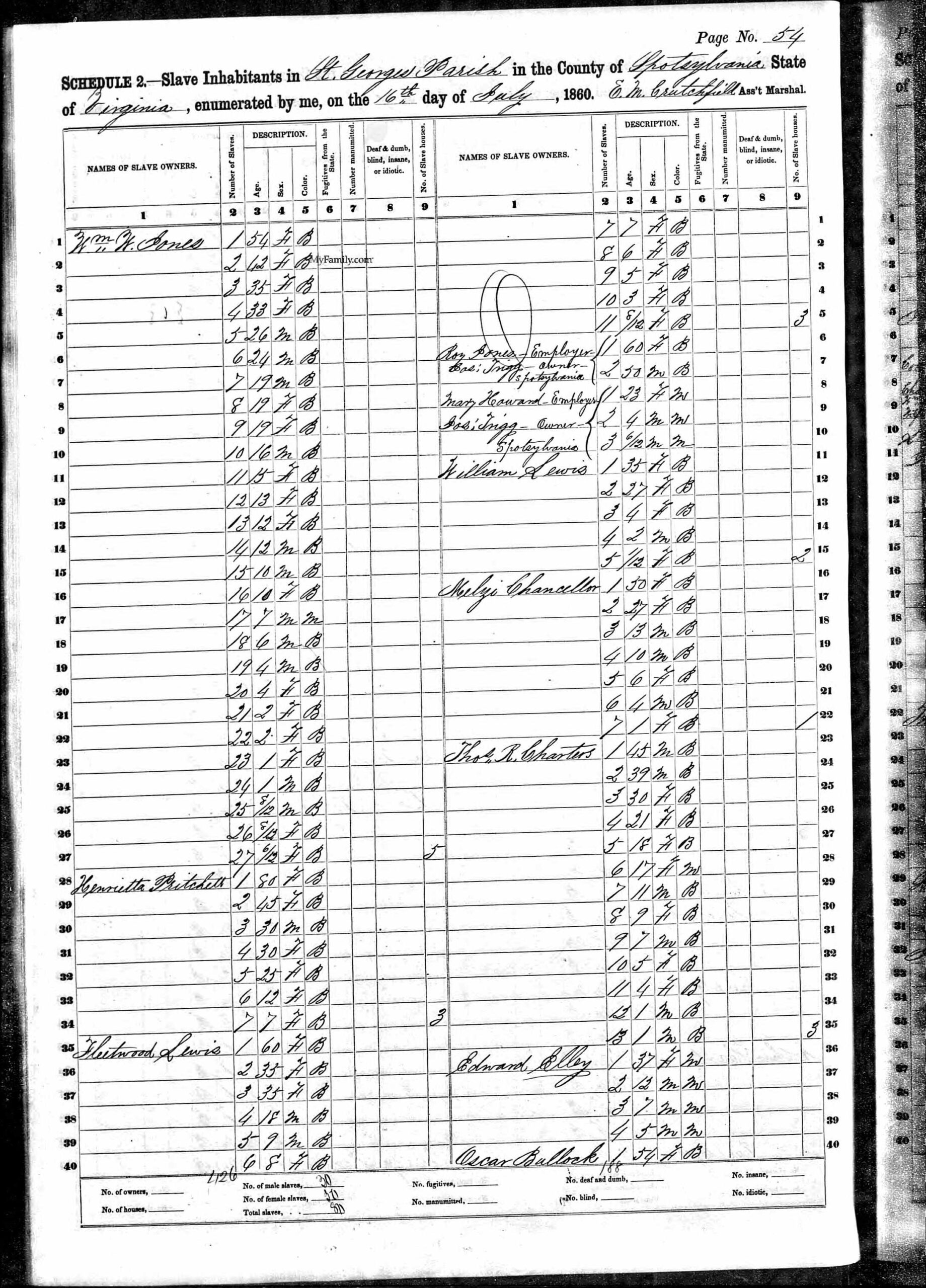

Figure 2: A page from the 1860 U.S. Census Slave Schedule for Spotsylvania County in Virginia (U.S. Slave Schedules 1860).

With the names of slaveholders and the likely county where they lived, researchers can use the 1860 U.S. Federal Population Census Slave Schedule (U.S. Slave Schedules) to determine the number of people they enslaved, along with their ages and genders. Was the impressed laborer part of a small, enslaved household of four to six people, or a large plantation with dozens? (Figure 2) An additional research avenue is taking the impressed laborers’ names and searching through the Compiled Military Service Records (CMSR) of the U.S. Army. Tens of thousands of formerly enslaved African Americans enlisted in the Federal military as U.S. Colored Troops (USCT) in the second half of the war, and their service records often included the names of their enslavers. Matching the names of the slaveholders from the impressment rolls can aid in confirming the identities of impressed laborers who eventually became USCT. One difficulty in locating impressed workers-turned-USCT is that the militaries’ labor rolls typically listed enslaved people with their enslavers’ last name. Many Black men retained their enslaver’s surname when they enlisted, while others chose to change it, making it difficult or even impossible to confirm the identities of these former impressed laborers.

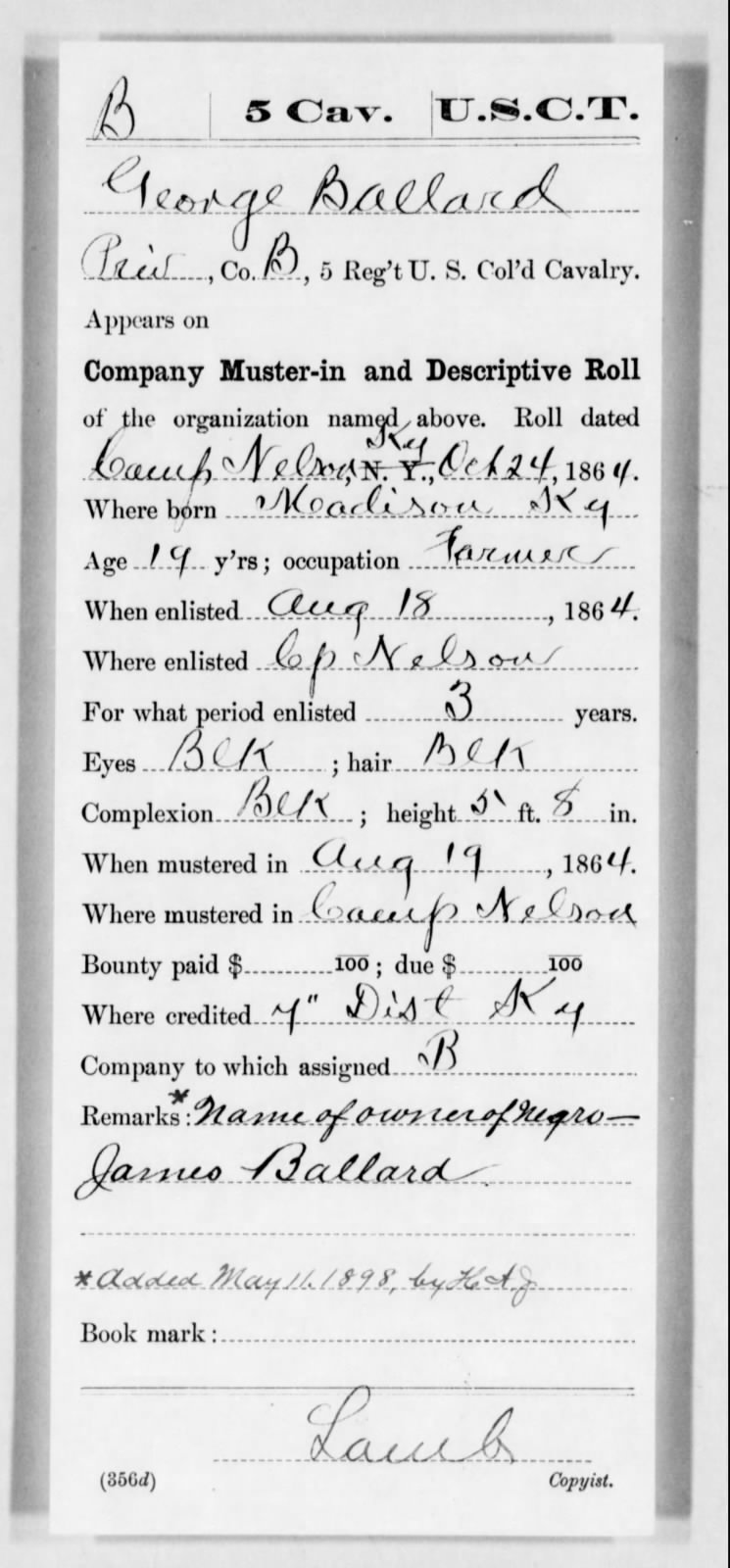

Figure 3: An enlistment page from the Compiled Military Service Record of George Ballard, a formerly impressed enslaved laborer who became a U.S. Colored Troop in Kentucky in 1864 (CMSR n.d.).

Military service records are filled with data related to individual soldiers, from basic background information like age and birthplace to bimonthly status reports tracking rank, duties, and involvement with the unit’s operations (Figure 3). A contemporary researcher looking through a service record can learn if a soldier was determined to be unfit for duty due to illness, was ever punished for a disciplinary problem, and the time and place of their discharge from the army, or alternatively, if they died during their service from combat or sickness. A formerly enslaved Black soldier may not have described his time in the military in a letter, diary, or memoir, but his service records tell their own story of his wartime experiences. Certainly, it is a limited and one-sided story, unable to reflect the personal reality of his life as a soldier, but it preserves crucial details that might have otherwise been lost to time.

Chronicling the experiences of enslaved people who were exploited as impressed laborers and/or enrolled in the military as USCT does not have to end with the close of the Civil War in 1865. Searching their names in the 1870 U.S. Census records can offer information on their postwar lives. Did they have a family? What part of the country were they living? What was their occupation? Did they own property? It can be possible to continue tracking these individuals through subsequent censuses, providing broad snapshots of their lives. Moreover, other types of military records remain invaluable sources of information, as the U.S. government awarded pensions to veterans and their widows throughout the late nineteenth century. Pension applications typically included details explaining the need for financial support, documenting the veteran’s service history, injuries, illnesses, and postwar hardships. These records offer insights into the long-term effects of military service on formerly enslaved soldiers and their families—struggles that may never have been written down elsewhere by the individuals themselves.

All of these diverse records—impressment labor rolls, census data, military service records, and pension applications—are preserved by the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). They are publicly accessible, and many have been digitized for online access. Impressment rolls can be found in the National Archives digital catalog, while military service and pension records are available on the Fold3.com database, and census materials can be accessed through Ancestry.com (references to the different records are listed below). Learning about formerly enslaved people and their experiences during the Civil War era can be challenging, but examining these records and piecing together information helps bring their stories to light. Researchers can uncover the lives of individuals who may have left little to no written accounts of their own. Though incomplete, these documents offer crucial insights into their experiences and contribute to a deeper understanding of the Civil War as a whole.

References

Compiled Military Service Records (CMSR)

n.d. U.S. Civil War. Washington, D.C. National Archives and Records Administration. Electronic document, https://www.fold3.com/, accessed March 2025.

National Records and Archives Administration (NARA)

1864 Impressment Labor Rolls of the U.S. Army Quartermaster at Camp Nelson. Record Group 92: Records of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. Washington, D.C. National Records and Archives Administration.

2020 Confederate Slave Payrolls Shed Light on Lives of 19th-Century African American Families. Washington, D.C. National Archives and Records Administration. Electronic document, https://www.archives.gov/news/articles/confederate-slave-payrolls-digitized, accessed March 2025.

U.S. Civil War Pensions Applications, 1861–1900

n.d. Pension Files of Veterans Who Seved Between 1861 and 1900. National Archives and Records Administration. Electronic document, https://www.fold3.com/, accessed March 2025.

United States Federal Population Census (U.S. Census)

1870 Ninth Census of the United States, 1870. Washington, D.C. National Archives and Records Administration. Electronic document, www.ancestry.com, accessed March 2025.

United States Federal Population Census – Slave Schedules (U.S. Slave Schedules)

1860 1860 U.S. Federal Census – Slave Schedules. Washington, D.C. National Archives and Records Administration. Electronic document, www.ancestry.com, accessed March 2025.

The post Uncovering African American Lives in Civil War Records appeared first on Dovetail Cultural Resource Group, A Mead & Hunt COmpany.

More than Scratching the Surface: Scratch-Blue Stoneware in Delaware 24 Feb 2025, 3:55 pm

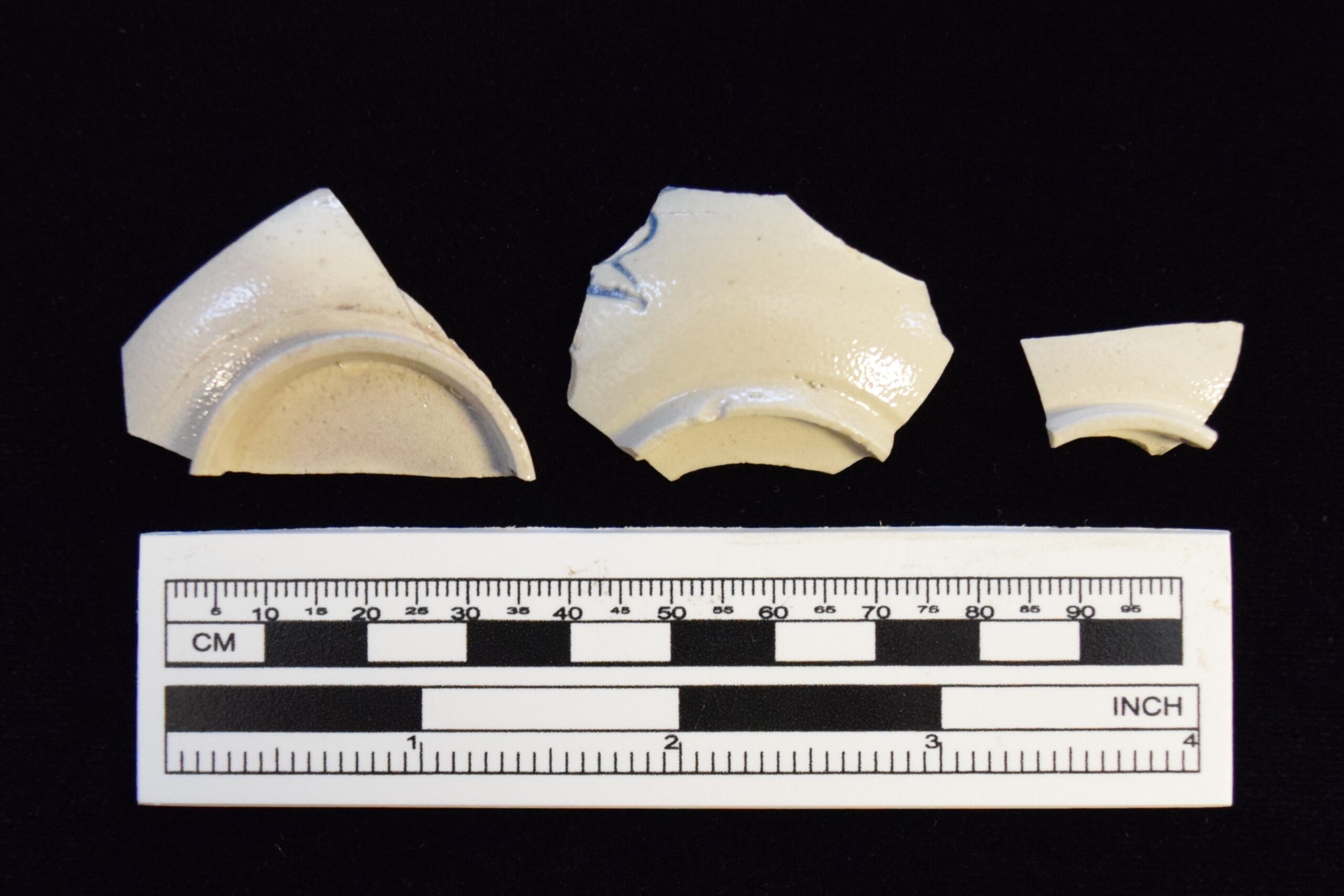

Photo 1: Scratch Blue Teaware Fragments Recovered from the Top of a Well.

By Colleen Betti

Over the past month, archaeologists from Dovetail Cultural Resource Group (Dovetail), a Mead & Hunt company, have been working on a data recovery project in Sussex County, Delaware. Data recovery excavations occur ahead of site impacts to recover the artifacts from a site as well as document and excavate features—the nonportable evidence of past lives such as foundations, wells, and hearths. The site appears to have been a domestic site occupied in the second and third quarters of the eighteenth century. Remains of a well and pits with domestic refuse were found. Although we are still in the early stages of site analysis, it appears that the occupants of the site were of a lower socio-economic status, possibly enslaved or poor tenant farmers. Ceramics were the most common artifacts found at the site, after clam and oyster shell. While redwares, especially cheaper domestically produced redwares, dominated the ceramic assemblage, there were also approximately 30 scratch blue ceramic sherds representing multiple vessels. White salt-glazed stoneware, and the scratch blue variant in particular, were the only stoneware found during the data recovery excavations. There were almost double the number of scratch blue sherds compared to tin-glazed earthenware sherds and only three Chinese porcelain fragments. No other imported stonewares like Westerwald or Fulham were found. Despite their low socioeconomic status, why would the residents of Walden have scratch blue vessels in larger numbers than tin enamel wares or other imported stonewares like Westerwald?

Photo 2: Interior of the Scratch Blue Teacup Rims from the Well. Note the three lines on the left three pieces and two on the fragment on the right, indicating they belong to different vessels. Additionally, one of the pieces with three lines has a band on the exterior (see Photo 1) indicating it also belongs to a different cup.

Scratch blue is a variation of the popular white salt-glazed stoneware. White salt-glazed stoneware, which began being manufactured in England in the late seventeenth century, was most popular between 1720 and 1770. It was the most widely used tableware and teaware in England from 1720 until creamware was introduced in the 1760s, and that tradition carried over to the Americas. Scratch blue, made by incising lines in the surface of the vessel before it was fired and infilling them with cobalt blue oxide, began being produced in 1742 and was made until 1778. It dominated the white salt-glazed stoneware market between 1742 and 1750. A “debased” version where the cobalt blue oxide was less carefully applied and spread outside of the incised lines, began being produced in 1760 to compete with another style/form called Westerwald and was made through the 1790s. Scratch blue vessel forms included teaware, especially cups and saucers, chamber pots, pitchers, mugs, and punch bowls (Maryland Archaeological Conservation Lab 2015; Noel Hume 1969). Teacups and saucers are the most common scratch blue vessel forms found in what is now the United States (Skerry and Hood 2009). All the scratch blue from the data recovery site appears to be teaware, and it is all the original neat version, not debased. Sherds from at least three separate teacups were found in the well along with at least two saucers. An undecorated white salt-glazed stoneware lid was also found in the plow zone, suggesting that the site occupants may have only purchased fancier scratch blue vessels as cups and saucers, not the entire tea set.

Photo 3: Scratch Blue Saucer Bases from the Well.

Photo 4: White Salt-Glazed Stoneware Lid, Possibly from a Teapot.

So, what made scratch blue so popular? And why was it the most common ware type at the data recovery site, outside of redware? In the mid-eighteenth century, white salt-glazed stoneware filled a gap in the market. It was more affordable than imported Chinese porcelain, sturdier than the soft-pasted tin enameled wares, and more aesthetically pleasing for display than plain white salt-glazed stoneware or coarse earthenwares (McMahon 1984). While slipwares, which are coarse earthenwares decorated with slip, a thin colored clay, often in linear patterns, were affordable and common in the eighteenth century (and many were found at the data recovery site), they were thicker, clunkier, and decorated in muted earthtones and often served more utilitarian functions. Scratch blue imitated the designs, colorways, and delicate nature of Chinese porcelain without the hefty price tag. It replaced tin-enameled wares, which had served a similar function, but were more fragile, since tin-enamel glazes are more prone to flaking off the vessel body (McMahon 1984). Despite their lower socio-economic status, the residents of the data recovery site wanted to participate in the growing culture of the tea ceremony. Throughout the eighteenth century in England, and in the English colonies like Delaware, tea drinking became a crucial part of social life and manners with a set ceremony, and the material goods linked with tea drinking, were a way to show status (Roth 1961). An entire Chinese porcelain set was likely outside of their budget, so individual scratch blue pieces served to elevate a more affordable, white salt-glazed stoneware tea set. No matter what time period, people of all socioeconomic statuses participate in changes in styles and the latest trends. The purchasing of scratch blue teawares rather than Chinese porcelain is not so unlike modern Americans buying the recently released $80 Walmart Wirkin Bag, an imitation of the much more expensive Hermes Birkin Bag, for those that cannot spend $30,000 or more for a handbag.

References

Maryland Archaeological Conservation Lab

2015 Diagnostic Artifacts in Maryland. Electronic document, https://apps.jefpat.maryland.gov/diagnostic/, accessed February 2025.

McMahon, Dawn Fallon

1984 Requa Site Scratch Blue White Saltglaze Stoneware. The Bulletin and Journal of Archaeology for New York State 89:30–43.

Noël Hume, Ivor

1969 A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

Roth, Rodris

1961 Tea Drinking in 18th-Century America: Its Etiquette and Equipage. United States National Museum Bulletin 225. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Skerry, Janine E., and Suzanne Findlen Hood

2010 Salt-Glazed Stoneware in Early America. Colonial Williamsburg, Williamsburg, Virginia.

The post More than Scratching the Surface: Scratch-Blue Stoneware in Delaware appeared first on Dovetail Cultural Resource Group, A Mead & Hunt COmpany.

A Day in The Life of an Artifact 23 Jan 2025, 5:47 pm

Figure 1: Artifacts from the field are brought to the lab and placed in a crate to be checked in.

By Sammy Lovette and Kat Baganski

Have you ever thought about the journey artifacts take after they have been discovered by archaeologists in the field? Once they get to the archaeological lab, a whole new adventure begins. The process is meticulously coordinated to keep artifacts organized and gather data for archaeologists to make site interpretations. This blog shares how our archaeological lab staff process an artifact.

Once archaeological fieldwork is completed, artifacts are brought to the lab and placed inside a crate to be sorted and checked in by lab staff (Figure 1). They also review field-based documentation prepared on site, including site notes, temporary artifact tags, and artifact logs, each describing what was found and first impressions of what the findings mean for the interpretation of the archaeological site.

Figure 2: Lab staff check in artifacts using a catalog prepared in the field and sort them by material type.

Working with one archaeological site collection at a time, lab staff complete a preliminary review of the artifacts using a log prepared by field staff to ensure that all artifacts are accounted for (Figure 2). During check in, artifacts are placed on a tray and are sorted by material type to prepare for washing. Since the artifacts are typically too dirty to accurately analyze at this stage, check in logs describe the collection in general terms and highlight objects that may turn out to have valuable research potential (Figure 3). At this time, inadvertently collected materials, such as modern garbage, plant roots, natural rocks, and excess amounts of soil, are removed and discarded.

Figure 3: Before washing, many artifacts are too dirty to accurately identify, such as the metal objects at the left.

Most artifacts are cleaned using plain tap water and a soft bristled toothbrush (Figure 4). Other tools, such as dental picks and pipe cleaners, can also be useful. Fragile materials, objects that may dissolve in or be damaged by water, and artifacts with residues valuable for analysis are treated on a case-by-case basis and may be dry-brushed or even left dirty for future processing and analysis.

Figure 4: Most artifacts are washed using plain tap water and a soft bristled toothbrush.

After all the dirt has been removed, the artifact is rinsed in a bowl of clean tap water to ensure no residue is left behind to cloud the surface (Figure 5).

Figure 5: After washing, artifacts are rinsed in plain tap water to remove lingering residue.

Each artifact is placed in a mesh tray atop a newspaper-lined rack to dry (Figure 6). Newspaper helps wick away moisture while the mesh tray keeps the artifact from coming in direct contact with the wet paper. Corresponding paper tags are kept with each artifact to ensure that the artifact is not separated from its key recovery information. All artifacts are left to dry for a minimum of 24 hours before being rehoused in clean polyethylene archaeological storage bags that are archivally stable and meet specific curation requirements.

Figure 6: Artifacts are allowed to dry for a minimum of 24 hours on a lined tray. Newspaper helps wick away extra moisture.

Once the artifacts are clean and dry, a detailed list of each object is created (Figure 7). This artifact cataloging process is completed by lab staff in consultation with our expert project archaeologists. Catalog entries for each artifact include as much relevant information as possible, from basic facts such as what the artifact is made of and general date ranges to things like unusual use ware patterns and identifiable maker’s marks. Sometimes, historic artifacts with patent numbers or unique lettering can be identified to the exact model, as with the cosmetic bottles pictured in Figure 7. Throughout the cataloging process, artifacts are assessed to determine the potential for a process called “cross-mending,” where pieces are pieced back together like a puzzle to try to recreate whole or partial vessels. If cross-mending is possible, this is documented within the catalog and completed during the final stages of artifact processing.

Figure 7: Occasionally, artifacts with patent numbers or unique maker’s marks can be identified to the exact product, such as this makeup set.

When an artifact is cataloged, it will usually be assigned a catalog number in accordance with state curation guidelines (Figure 8). Catalog numbers are unique to each artifact and encode information such as the site number, the year the fieldwork took place, and where the artifact was found. A standard way to affix an artifact catalog number to the surface of each object is by using B-72 in acetone as a base and then carefully writing the catalog number on each artifact using archival ink. The goal is to make sure that each artifact is labeled to understand details about its recovery while also being reversable and preservation friendly.

Figure 8: Catalog numbers are directly applied to stable artifacts using B-72 and archival ink.

After all analysis is completed for a project, the artifacts are delivered to a final repository for long-term storage. Depending on the nature of a project, that repository might be a state curation facility, the federal government, a municipality, or the personal collection of the private landowner who owns the site. Collections owned by the state and other public institutions are frequently used for public outreach, academic research, or incorporation into museum exhibitions.

This laboratory process ensures that our archaeologists and future researchers have access to the maximum amount of valuable information about each archaeological find, while also prioritizing the respectful and conscientious handling of cultural materials in our care. By sharing the carefully planned journey that each artifact takes through our lab, we hope to demonstrate the value we place in preserving our shared past and encourage you to do the same.

The post A Day in The Life of an Artifact appeared first on Dovetail Cultural Resource Group, A Mead & Hunt COmpany.

Sleigh Bells Ring, Are You Listening? 9 Dec 2024, 4:19 pm

Figure 1: Horse-Drawn Sleigh Showing a Strap of Bells (Nowell 1906).

By Sammy Lovette

The prominent mention of bells, particularly sleigh bells, in popular Christmas movies and music is astounding. Due to their close association with Christmas and winter, the horse bells began to be known as “sleigh bells” in the 1800s. This eventually led to the rise of the appearance of sleigh bells in popular culture (Classic Bells Ltd 2024a). Sleigh bells are referenced in “Winter Wonderland,” “Here Comes Santa Claus,” and, of course, “Jingle Bells.” Horse bells date back to the Roman era and were used to alert pedestrians of an approaching horse, sleigh, carriage, or wagon, especially when roads were narrow, dark, or had limited visibility due to snow or other factors (Liebeknecht 2021). Horses were equipped with bells attached to straps or harnesses that could be placed in various locations, including the neck, hips, and saddle (Figure 1). Wealthier families had a distinctive jingle to announce their approach.

During an archaeological survey at John Dickinson Plantation in Kent County, Delaware, Dovetail Cultural Resource Group, a Mead and Hunt Company, recovered a brass horse bell (Figure 2). The Dickinson Plantation bell is classified as a cast-petal bell due to the six-petaled, daisy-like flowers that adorn the opening of the bell (Liebeknecht 2021). The most[?] well-known bell-makers in North America in the 1800s and 1900s were the Wells family, Robert Wells and his two sons, Robert II and James Wells. The Wells family was known for their sleighs and bells, also known as “rumblers,” stamped with an RW makers mark (Classic Bells Ltd 2024a). Unfortunately, there are no makers marks on the Dickinson Plantation bell, and the manufacturing location is unknown.

The petal cast bell has been produced in America and Britain for at least 400 years and ranges from ¾ inch in diameter to 4 inches. The number of petals on the bell ranges from four to eight petals. This number depends on the bell’s size and the bell manufacturer. Petal cast bells always include a ridge around the middle and a shank base (Classic Bells Ltd 2024b). The shank of the bell is a piece of metal with a hole in it that protrudes from the bottom, allowing the bell to be attached to a strap via a metal pin. To affix a shank-style bell onto the strap, the shank is inserted into a slot in the strap, and a figure-eight-shaped metal pin is placed through the hole in the shank and twisted securely, fastening the bell to the leather strap (Classic Bells Ltd 2024c).

Figure 2: Brass Horse Bell Recovered from Site 7K-D-41 at the John Dickinson Plantation.

The start of the sleigh bell industry in America is credited to William Barton, who founded his bell factory in the early 1800s in East Hampton, Connecticut. Barton’s willingness to share his knowledge of the bell manufacturing process is the reason East Hampton is known as “Belltown” or “Jingletown” throughout the world (Classic Bells Ltd 2024a). The nature of Barton’s generosity truly embraces the spirit of Christmas and is to be admired, especially during this time of year. Whether an angel gets their wings every time a bell rings or believing in the magic of Christmas allows you to hear the ringing bells, one thing is sure: sleigh bells ring. Are you listening?

References

Classic Bells, Ltd

2024a History of Horse and Sleigh Bells. https://classicbells.com/info/History.asp, accessed December 2024.

2024b Petal Bells. https://classicbells.com/info/Petal.asp, accessed December 2024.

2024c Shank & Rivet Bells. https://classicbells.com/info/ShankRivet.asp, accessed December 2024.

Liebeknecht, Bill

2021 Delaware Discovery: A Metal Arrowhead and a Horse Bell from the John Dickinson Plantation. Bulletin of the Archaeological Society of Delaware 58:55–57.

Nowell, F. H.

1906 Mayor John S Copley and his wife in a horse-drawn sleigh. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mayor_John_S_Coply_and_his_wife_in_a_horse-drawn_sleigh,_April_5,_1906_(AL%2BCA_7507).jpg, accessed December 2024.

The post Sleigh Bells Ring, Are You Listening? appeared first on Dovetail Cultural Resource Group, A Mead & Hunt COmpany.

Worth a Pretty (Half) Penny 25 Sep 2024, 3:40 pm

By Kat Baganski

In 2006, in advance of construction of a new Marriott hotel in downtown Fredericksburg, Virginia, Dovetail Cultural Resource Group completed cultural resources investigations prior to construction and uncovered traces of a much earlier hotel, the Indian Queen. Before archaeological excavations began, documentary research suggested that beneath the extant parking lot chosen as the location for the new hotel, traces of an eighteenth-to nineteenth-century establishment with ties to the American Revolution might still be present. Archaeologists confirmed the location of the Indian Queen when excavations revealed the back wall of the hotel and a rear work yard.

View of the Indian Queen’s Foundation (Above) and the Tavern’s Rear Work Area (Below) During Archaeological Investigations.

The historic inn was established in 1771 as a hostelry by Jacob Whitely. Two years later, William Herndon purchased the business and renamed it the Indian Queen Tavern. For a time, the Indian Queen held the distinction of being Fredericksburg’s largest tavern and it remained in operation (later under the name the Indian Queen Hotel) until it burned to the ground in 1832 (Barile et al. 2008; Virginia Herald 1832). Due to its size and favorable location along the Philadelphia-Williamsburg postal route, the hotel existed as a popular meeting place and was patronized by many prominent families during its nearly 50 years in operation. Frequent visitors to the Indian Queen included the Washingtons, the Lees, and the Monroes (Barile et al. 2008). Other Revolutionary figures, including Thomas Jefferson and George Mason, were also known to frequent the hotel and even wrote the statute of religious liberty, a precursor to the Declaration of Independence, while staying at the Indian Queen (WPA 1937).

One of the more notable artifacts found was a 1773 copper half penny in excellent condition. The penny was found in the southeast corner of the proposed Marriott hotel site within a foot-thick layer of soil identified as part of the Indian Queen’s yard. Other artifacts found in the same context included ceramics and glassware associated with food preparation and dining, as well as personal items like tobacco pipes. The penny stands out within this assemblage because it was the first coin type minted that referred to Virginia as a state and the only coin with legal tender status minted for the American colonies. All other coins created for the American colonies prior to the Revolution are classified only as unofficial token money (Newman 1956). The dated coin also provides a terminus post quem, or date after which, that helps define the age of the soil deposits and archaeological materials.

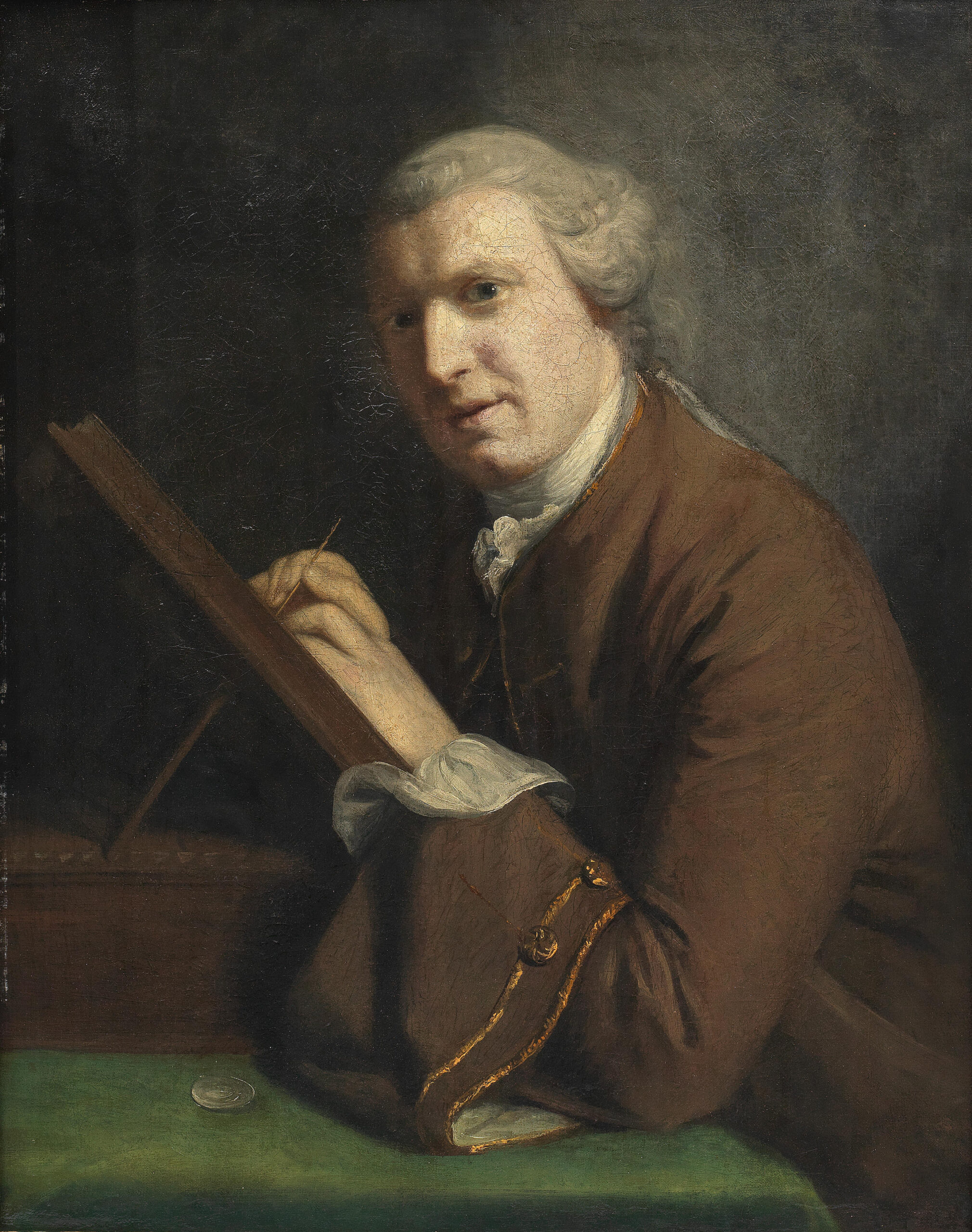

This half penny was created in 1773 by Richard Yeo (circa 1720 to December 3, 1779), engraver at the Royal Mint and founding member of the Royal Academy (National Portrait Gallery 2024; Royal Academy 2024). Although little is known about Yeo’s early life, he gained recognition in the later 1730s when he was tasked with the creation of silver season tickets to the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens. Yeo’s prominence grew in 1746 when he accepted a commission to create a commemorative medal celebrating the Duke of Cumberland’s victory over the Jacobites at the Battle of Culloden, with other notable medals to follow. In 1749, Yeo began his career as engraver (later, chief engraver) at the Royal Mint where he continued to work until his death (Royal Academy 2024).

Top Left: Coin Front; Top Right: Coin Reverse; Bottom: Sketch of Coin Stamp (Barile et al. 2008).

Recognizing a need for official coinage in the colonies, the Virginia Assembly authorized Yeo to strike a series of coins for circulation in Virginia including a half penny and prototypes of a penny and shilling (American Precious Metals Exchange [APMEX] 2022). A total of five long tons of half pennies, or about 672,000 coins, were purchased and delivered to the mouth of the York River in February 1774 (Bowers 1997:30). Several versions of the half penny exist with minor differences between them (APMEX 2022; Bowers 1997:31). The example from the Indian Queen Tavern features a left-facing laureate bust of King George III with the inscription “GEORGIVS · III · REX” on the front, while the reverse depicts the king’s heraldic shield surrounded by the inscription “1773 · VIRGINIA ·”. Although the coins had arrived in Virginia by early 1774, efforts to distribute the coins did not begin in earnest until late 1775 (Bowers 1997:30). By that time, existing wartime scarcities and increasing anxiety led to widespread hoarding of the new coins. Today, there are only 30 known examples of Yeo’s 1773 penny and a mere six of his shillings, but numerous half pennies exist in private collections, museums, and archaeological deposits yet to be unearthed (APMEX 2022). Thankfully, an early patron of the Indian Queen may have paid his bill with one of these unique coins, giving the archaeological team a “date” with destiny.

References

American Precious Metals Exchange (APMEX)

2022 Virginia Halfpennies – 1773-1774. Electronic document, https://learn.apmex.com/coin-guide/guide-to-colonial-values/virginia-halfpennies-1773-1774/, accessed September 2024.

Barile, Kerri S., Kerry Schamel-González, and Sean P. Maroney.

2008 “Inferior to None in the State”: The History, Archaeology, and Architecture of the Marriott Hotel Site in Fredericksburg, Virginia.” Dovetail Cultural Resource Group, Fredericksburg, Virginia.

Bowers, Q. David

1997 American Coin Treasures and Hoards and Caches of Other American Numismatic Items. Bowers and Merena, Wolfboro, New Hampshire.

National Portrait Gallery

2024 Richard Yeo. Electronic document, https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp04968/richard-yeo, accessed September 2024.

Newman, Eric P.

1956 Coinage for Colonial Virginia. Numismatic Notes and Monographs, No. 135. American Numismatic Society, New York.

Reynolds, Sir Joshua

1723-1792 Portrait of Richard Yeo, half-length, in a brown coat, seated at work with a medal on the table, oil on canvas, 77.8 x 62.3cm (30 5/8 x 24 1/2in), Bonhams, Old Master Paintings, Lot 11, https://www.bonhams.com/auction/28250/lot/11/sir-joshua-reynolds-plympton-1723-1792-richmond-portrait-of-richard-yeo-half-length-in-a-brown-coat-seated-at-work-with-a-medal-on-the-table/, accessed September 2024.

Royal Academy

2024 Richard Yeo RA (ca. 1720 – 1779). Electronic document, https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/name/richard-yeo-ra, accessed September 2024.

Virginia Herald

1832 Fire! April 28, 1832. Page 3, column 1.

Works Progress Administration Inventory (WPA)

1937 Cassiday’s Drug Store, formerly known as Indian Queen Tavern. Volume I, pp. 206–210. On file, Central Rappahannock Regional Library, Fredericksburg.

The post Worth a Pretty (Half) Penny appeared first on Dovetail Cultural Resource Group, A Mead & Hunt COmpany.

Are Horseshoes Truly a Symbol of Good Luck? Analysis of Horseshoes on Battlefields from Virginia 17 Jul 2024, 6:56 pm

Civil War battlefields are quite common across Central Virginia. With population growth and associated developments in the region, local groups are striving to protect former battlefield grounds for future generations. Dovetail Cultural Resource Group (Dovetail), a Mead & Hunt company, is very proud to assist these groups with their preservation goals to help research the history of these important areas and perform archaeological studies to learn about the artifacts that soldiers may have left behind.

Historical interpretations of battlefields often describe the regiments were involved, the location of earthworks and battle lines, and the outcome of the engagement. More recently, scholars are assuring that the narratives go beyond the battle to include the experiences of the soldiers who fought in the war and the citizens who were deeply impacted by war-related occupation. Archaeological research brings in another dimension to the story as we study what was physically discarded or left behind. Not only do artifacts such as musket balls and bullets tell us crucial information about Civil War weaponry and combat, but the items scattered across battlefields and camps reveal information about soldiers’ daily activities and lives. For this blog, I wanted to talk about an artifact type that many would consider commonplace but which tells a key side of battlefield logistics and daily life in the 1860s—the horseshoe.

Horses and mules were critical for the operations of Civil War armies. Horses supplied necessary mobility for men and artillery, while mules were utilized as draft animals, pulling the wagons and carrying the supplies that supported thousands of soldiers on the move. A sobering statistic is that deaths were higher for horses and mules than men; it is estimated that of the 3 million horses and mules that served during the Civil War, more than 1.2 million died compared to around 620,000 soldiers (Bainbridge 2021; Reichard and Grabowski 2017).

Horseshoes were vital to the health of horses. They served a number of functions: added traction, improved balance, and strengthened and protected hooves for medical reasons. Horses and mules in the Civil War-period would have encountered varied terrains, heavy workloads, and long-distance traveling. Good shoes were essential and with heavy use, these animals needed to be reshod often (Bainbridge 2021; Horse and Country TV 2024).

Horseshoes are artifacts that have not changed greatly since the seventeenth century. Their size and shape are dependent on the animal and the style or skill of the blacksmith or farrier. Figure 1 shows the parts of the horseshoe. Nineteenth-century horseshoes typically have calkins (a type of metal cleat), heels that are slightly curved outward, and toe clips or reinforcing bars (Bainbridge 2021; Chappell 1973:102, 105, 106, and 109).

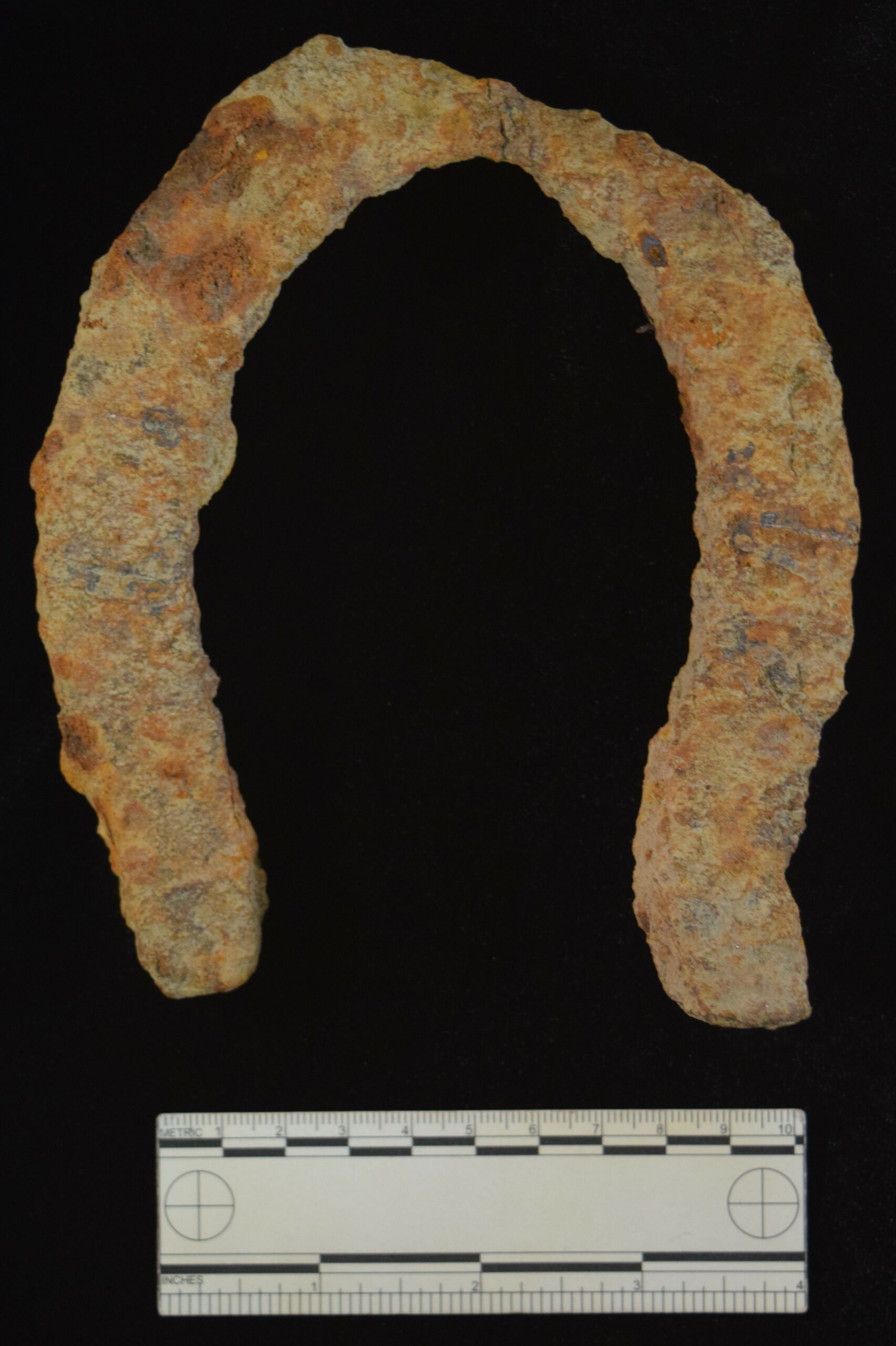

Photo 1: Examples of Mule Shoes. Photo by Dovetail.

Horseshoes were hand-made until Henry Burden’s first patent in 1835 that included the use of three separate machines for manufacturing. In 1857, he had perfected the ability of one machine to cut, bend, and forge a shoe. At its peak, Henry Burden and Sons could produce approximately 2,600 horseshoes per hour of various sizes for riding horses, mules, and draft horses. With his factories located in Troy, New York, the United States (U.S.) Army benefited greatly from his factories. These horseshoes were so important that the Confederacy unsuccessfully sent spies to learn how to replicate his horseshoe-making machines and sent raiding parties to block or capture their shipments from railroads or wagon trains (Bainbridge 2021).

When conducting archaeological surveys at battlefields in Central Virginia, horseshoes are one of the most prevalent types of artifacts that are discovered. On one such site recently surveyed by Dovetail, 29 shoes were recovered. In-depth analysis and further research on these horseshoes are revealing the types of horses and draft animals that were present and how they were treated in the battlefield environment.

While the vast majority of horseshoes appear to have been specifically for horses, the grouping from the recent Dovetail survey contained four shoes that were different. Three complete mule shoes and one mule/pony shoe fragment were recovered. Mule shoes have a more-rounded toe shape with straighter sides than those specifically for horses. These examples were also of a narrower width of only 4.0 to 4.5 inches and a length of 4.5, 5.75, and 6.0 inches. The other fragmented shoe still maintained its reinforcing bar, but its calkin/heel was fragmented or worn off. It was also about 4.0 inches wide and approximately 4.5 inches long. No oxen shoes were identified (Blumenstein 1968).

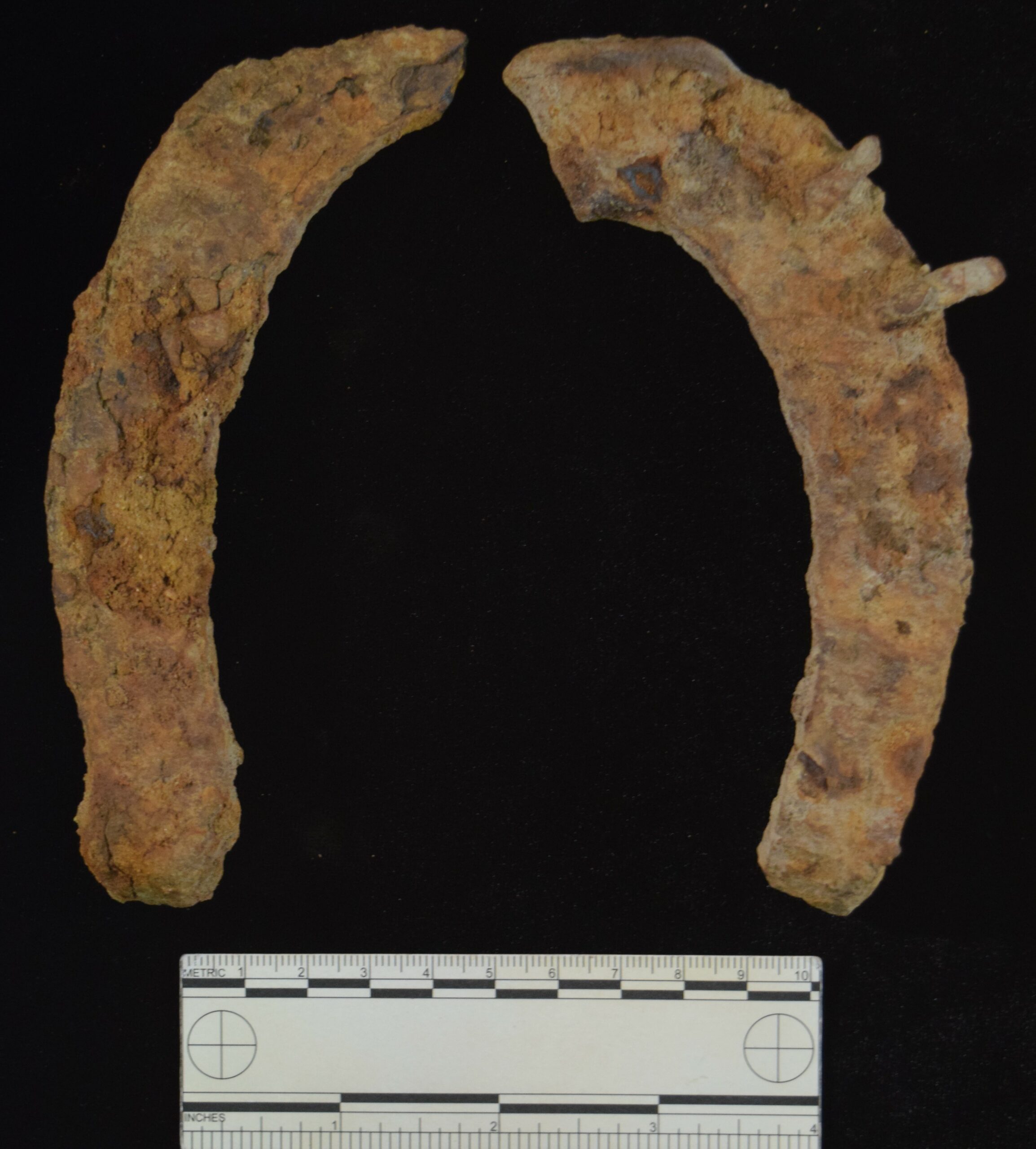

Photo 2: Complete Horseshoe. Photo by Dovetail.

Of the horseshoes found, only two were complete. Neither exhibited a reinforcing bar, and they both measured 5.75 inches in length. One example exhibited a large diagonal wear pattern across the toe while the other was twisted. These shoes were quite sizeable in length and probably were utilized on some of the bigger horses. The remaining horseshoes were fragmentary in nature. Most appear to be horseshoe fragments, but several might be mule shoe fragments. Interestingly, 23 shoe fragments were broken at almost the exact same spot—at the top approximately halfway across the toe. Only a few shoes still had the corresponding nails still in the horseshoe. Interestingly, many shoe fragments could be defined as to which side of the hoof they belonged; eight shoes were from the left side, eight sides were from the right side, and seven fragments could not be determined. The majority of the horseshoe fragments measured between approximately 4.0 and 6.0 inches in length, corresponding to the wide variety of sizes in horses and draft animals used by both the Confederate and U.S. armies.

Photo 3: Horseshoe Fragments. Photo by Dovetail.

Overall, all shoes showed extreme wear use. Even with their rusted surfaces, every shoe exhibited extremely worn surfaces, particularly in the heel/calkin and toe areas. The number of broken shoes also suggests that many horses might have worn shoes much longer than recommended. In fact, I would not be surprised if many horses had their shoe actually fragmented on their hooves while still being worn.

The archaeological evidence suggests that while Civil War soldiers heavily utilized horses, they often did not (or could not) care properly for their animals when it came to horseshoes. Horses and mules were vital to the logistics and movements of both the Confederate and U.S. armies, but the issues with the repair of their shoes was detrimental. Veterinary medicine did not truly exist during the Civil War period, and soldiers did the best that they could under the circumstances to take care of the animals. In fact, Confederate cavalrymen were responsible to provide their own mount, care for it, and find a replacement if it died. Even the U.S. Army’s Quartermaster Department was upset at the unnecessary animal casualties due to neglect (Reichard and Grabowski 2017).

Would I say that a horseshoe was good luck if I was a horse during the Civil War? I think not!

References

Bainbridge, David A.

2021 How Horseshoes Helped Win the Civil War. American Farriers Journal. Electronic document, https://www.americanfarriers.com/articles/12850-how-horseshoes-helped-win-the-civil-war, accessed July 2024.

Blumenstein, Lynn

1968 Wishbook 1865: Relic Identification for the Civil War Era. Old Time Bottle Publishing Company. Salem, Oregon.

Chappell, Edward

1973 A Study of Horseshoes in the Department of Archaeology, Colonial Williamsburg. In Five Artifact Studies, edited by Audrey Noel Hume, Merry W. Abbitt, Robert H. McNulty, Isabel Davies, and Edward Chapell, pp. 100-116. Colonial Williamsburg Occasional Papers in Archaeology. Volume I, Williamsburg, Virginia.

Horse and Country TV

2024 Do Horses Need Shoes? The Pros and Cons of Shoeing. Electronic document, https://horseandcountry.tv/en-us/why-do-horses-need-shoes-horse-shoeing-guide/#why-do-horses-wear-shoes, accessed July 2024.

Reichard, Katie, and Amelia Grabowski

2017 “Every Man His Own Horse Doctor”. National Museum of Civil War Medicine. Electronic document, https://www.civilwarmed.org/animal/, accessed July 2024.

The post Are Horseshoes Truly a Symbol of Good Luck? Analysis of Horseshoes on Battlefields from Virginia appeared first on Dovetail Cultural Resource Group, A Mead & Hunt COmpany.

Enduring Wet Weather in the Civil War 5 Jun 2024, 6:14 pm

By Cameron Boutin

This blog is by Dovetail Historian Cameron Boutin, who is sharing just some of his fascinating dissertation research on soldiers during the Civil War.

United States (U.S.) and Confederate soldiers in the Civil War experienced the pressures of weather in a variety of ways over the course of their military service. The weather was not simply a passive backdrop to their time in the army; it was a central preoccupation. While this could be said about most people in mid-nineteenth-century America, wartime service necessitated much longer lasting exposure to the elements then life at home. One of the things that sets the soldier’s encounters with the weather apart from others was that they essentially had no reprieve. They lived outside for years at a time. Who else in nineteenth-century American society lived outside continuously for years? The weather intersected with some of the most central experiences of soldiering, from tent camping and marching to performing sentry duty and fighting on the battlefield. Most men understood that enduring the vagaries of the weather was a necessary part of war, but most nevertheless believed that bad weather made life in the military much more difficult and disagreeable.

One of the most frequent sources of hardships for soldiers was wet and stormy weather. Men spent the majority of their service in encampments, living in different types of tents, ranging from large and fully enclosed models to smaller and lightweight ones such as the commonly used open-ended shelter tents (Figure 1). No matter the type of tent, inclement conditions usually exceeded their capacity to shield against the elements, particularly heavy rain. Water leaked through canvas roofs or flowed across the ground into tents, flooding the shelters with inches or even feet of water. Soldiers’ bodies and possessions became drenched, interfering with their ability to sleep and forcing them to live in a persistent state of wetness until the rain subsided. In December 1862, Pennsylvania Corporal Calvin S. Heller penned in his diary in Virginia: “It is not a very pleasant [sic] affair, to be roused from one’s slumber by a flood underneath and the pouring down of the wartery [sic] elements from above” (Heller 1862). The strong winds that could accompany storms caused still more problems. Tents were commonly blown down and collapsed onto the occupants, who had to extricate themselves from the wet canvas and were left exposed to the falling rain.

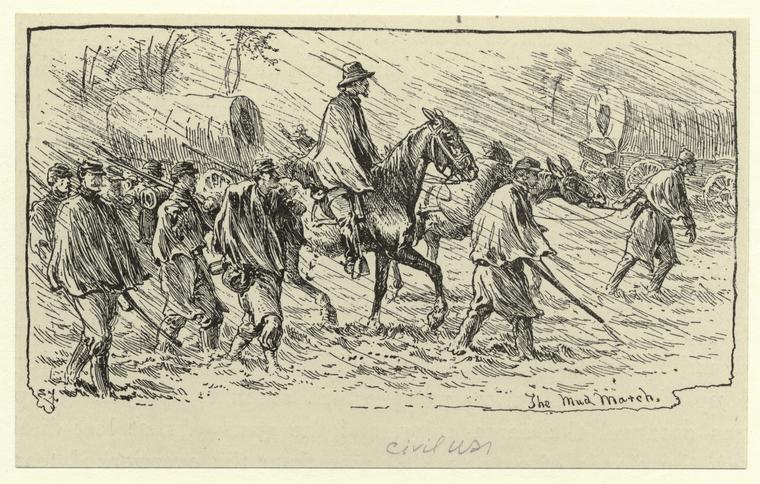

Men found themselves soaked when they had to march, occupy field fortifications, or fight in rainstorms, but a much greater problem was the wet weather’s impact on the terrain, turning the soil into gooey mud. The remarkably deep mud encountered by soldiers stemmed from the clayey soil composition of large portions of the South. Reflecting the thoughts of countless troops, Maine Private John Haley complained in June 1863 during the Gettysburg Campaign, “It commenced to rain in fine old Virginia style, and in less than an hour the road was a mass of liquid mud up to, even over, our ankles in many places” (Silliker 1985). With most of the roads in the South composed of dirt, marching men had to trudge through various depths of mud whenever it rained. Marching through mud was exhausting, and men struggled to maintain their footing, regularly slipping, sliding, and stumbling and even becoming stuck (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Federal troops moving through the rain and mud in Virginia during the infamous Mud March of January 1863 (Forbes 1863).

On the battlefield, muddy terrain made it challenging for troops to maneuver and engage the enemy, with the side on the offensive usually at the disadvantage because the nature of their operations required greater mobility than the side fighting on the defensive, which could remain more stationary. For example, at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House in May 1864, a Mississippi private recalled: “Soon the Yanks made a determined charge with fixed bayonets, but the mud fought for us. Many of them were shot dead and sank down on the breastworks without pulling their feet out of the mud” (Cockrell and Ballard 1995). Besides the mud, wet weather could have a devastating effect on firearms, rendering them faulty or even inoperable in various military actions. In some engagements, pervasive wetness caused troops’ weapons to misfire, preventing them from offering serious resistance to their opponents. At Spotsylvania for instance, an attacking Federal force was able to overrun a salient in the enemy defensive line because many of the Confederates could not blunt the U.S. assault due to their rain-impaired muskets (Figure 3).

Figure 3: U.S. and Confederate soldiers fought for almost 24 hours amid stormy weather at Spotsylvania Court House, Virginia, on May 12, 1864 (Thulstrup 1887).

Facing such a wide range of problems, troops devised methods to combat wet weather, improvising and using any means available alleviate its difficulties. Some of these adaptions were simple. Men living in tents learned to dig small ditches around the perimeter of their shelters to prevent flooding, to securely stake their tents to withstand wind gusts, and to build makeshift beds using hay, brush, or other available materials to stay off the saturated ground. To make slogging through rain and mud easier, they learned to carry only the equipment that they considered the most essential for their survival. Others employed coping mechanisms to help mentally endure, such as swearing as an emotional release or distracting themselves through humor. Marching troops, for instance, made jokes and laughed in amusement as they watched comrades fall or get stuck in muddy roadways.

The material items typically issued to soldiers had a critical role in shaping their experiences with the weather. To these men, tents, uniforms, blankets, and other pieces of equipment were much more than just stuff. No matter the facet of wartime service, troops who possessed or had access to sufficient equipment often fared better when it came to adverse weather than those men who did not. In rainy conditions, soldiers hoped to possess the different types of waterproof blankets. Soldiers would lay on, cover their bodies with, or wrap the blankets around themselves while trying to sleep in camp, standing on guard duty, or marching through the rain (Gaede 2022). They were a versatile item that men never wanted to be without when the weather was bad. At a Mississippi camp in January 1863, Missouri (U.S.) Lieutenant Henry Kircher noted, “I wrapped myself in my rubber blanket and let it rain to its heart’s content without getting wet” (Hess 1983). Against the mud, there was no more important weapon than soldiers’ footwear. The standard shoe for infantrymen was ill-suited for rainy weather, allowing men’s feet to become soaked. Consequently, when storms raged and the ground became viscous mud, soldiers preferred to have high leather boots, which were much more water resistant. Infantrymen were not issued high boots and had to procure them on their own, with many writing home requesting that their families send them. No matter how they obtained boots, soldiers were appreciative for the protection and comfort they provided. After a muddy march in early 1863 in Virginia, New York Corporal John Hartwell contended, “I never had anything that did me more good or that I was more thankful for than those boots” (Britton and Reed 1997).

Through their struggles against rain as well as the heat and cold, Civil War soldiers generally became more successful at adjusting to the rigors of weather over the course of their service as they accumulated knowledge and experience across the varying terrain of the war. Adapting to the difficulties of weather helped men survive the conflict and turned out to be a critical element in how common soldiers became hardened veterans.

Figures

Figure 1: Rows of tents at a U.S. Army encampment in Virginia in May 1862 during the Peninsula Campaign (Library of Congress 1862).

Figure 2: Federal troops moving through the rain and mud in Virginia during the infamous Mud March of January 1863 (Forbes 1863).

Figure 3: U.S. and Confederate soldiers fought for almost 24 hours amid stormy weather at Spotsylvania Court House, Virginia, on May 12, 1864 (Thulstrup 1887).

References

Britton, Ann Hartwell, and Thomas J. Reed, editors.

1997 To My Beloved Wife and Boy at Home: The Letters and Diaries of Orderly Sergeant John F.L. Hartwell. Associated University Presses, London.

Cockrell, Thomas D., and Michael B. Ballard, editors.

1995 A Mississippi Rebel in the Army of Northern Virginia: The Civil War Memoirs of Private David Holt. Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge.

Forbes, Edwin

1863 The Mud March. New York Public Library, Wallach Division Picture Collection, New York. Electronic document, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e0-e7e4-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99, accessed May 2024.

Gaege, Frederick C.

2022 Ponchos and Waterproof Blankets During the Civil War. Military Images 40, no. 2. Pp. 70–74.

Heller, Calvin S.

1862 Calvin S. Heller Diary. Civil War Document Collection, U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Hess, Earl J., editor.

1983 A German in the Yankee Fatherland: The Civil War Letters of Henry A. Kircher. Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio.

Library of Congress

1862 Cumberland Landing, Va. Federal encampment; view from tree. Library of Congress, Geography and Maps Division, Washington, D.C. Electronic document, https://www.loc.gov/item/2018666158/, accessed May 2024.

Silliker, Ruth L., editor.

1985 The Rebel Yell & the Yankee Hurrah: The Civil War Journal of a Maine Volunteer. Down East Books, Lanham, Maryland.

Thulstrup, Thure De

1887 Battle of Spottsylvania [sic]. Library of Congress, Geography and Maps Division, Washington, D.C. Electronic document, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/90712278/, accessed May 2024.

The post Enduring Wet Weather in the Civil War appeared first on Dovetail Cultural Resource Group, A Mead & Hunt COmpany.

Milk, Medicines, and Mammoth Cave? Let’s Talk About 20th Century Glass Bottles 15 May 2024, 7:45 pm

Photo 1: Sprite Bottle Base Featuring Mammoth Cave National Park Embossing.

By Cameron Boutin

This blog is by Dovetail Historian Cameron Boutin, who is sharing just some of his fascinating dissertation research on soldiers during the Civil War.

United States (U.S.) and Confederate soldiers in the Civil War experienced the pressures of weather in a variety of ways over the course of their military service. The weather was not simply a passive backdrop to their time in the army; it was a central preoccupation. While this could be said about most people in mid-nineteenth-century America, wartime service necessitated much longer lasting exposure to the elements then life at home. One of the things that sets the soldier’s encounters with the weather apart from others was that they essentially had no reprieve. They lived outside for years at a time. Who else in nineteenth-century American society lived outside continuously for years? The weather intersected with some of the most central experiences of soldiering, from tent camping and marching to performing sentry duty and fighting on the battlefield. Most men understood that enduring the vagaries of the weather was a necessary part of war, but most nevertheless believed that bad weather made life in the military much more difficult and disagreeable.

One of the most frequent sources of hardships for soldiers was wet and stormy weather. Men spent the majority of their service in encampments, living in different types of tents, ranging from large and fully enclosed models to smaller and lightweight ones such as the commonly used open-ended shelter tents (Figure 1). No matter the type of tent, inclement conditions usually exceeded their capacity to shield against the elements, particularly heavy rain. Water leaked through canvas roofs or flowed across the ground into tents, flooding the shelters with inches or even feet of water. Soldiers’ bodies and possessions became drenched, interfering with their ability to sleep and forcing them to live in a persistent state of wetness until the rain subsided. In December 1862, Pennsylvania Corporal Calvin S. Heller penned in his diary in Virginia: “It is not a very pleasent [sic] affair, to be roused from one’s slumber by a flood underneath and the pouring down of the wartery [sic] elements from above” (Heller 1862). The strong winds that could accompany storms caused still more problems. Tents were commonly blown down and collapsed onto the occupants, who had to extricate themselves from the wet canvas and were left exposed to the falling rain.

Men found themselves soaked when they had to march, occupy field fortifications, or fight in rainstorms, but a much greater problem was the wet weather’s impact on the terrain, turning the soil into gooey mud. The remarkably deep mud encountered by soldiers stemmed from the clayey soil composition of large portions of the South. Reflecting the thoughts of countless troops, Maine Private John Haley complained in June 1863 during the Gettysburg Campaign, “It commenced to rain in fine old Virginia style, and in less than an hour the road was a mass of liquid mud up to, even over, our ankles in many places” (Silliker 1985). With most of the roads in the South composed of dirt, marching men had to trudge through various depths of mud whenever it rained. Marching through mud was exhausting, and men struggled to maintain their footing, regularly slipping, sliding, and stumbling and even becoming stuck (Figure 2).

On the battlefield, muddy terrain made it challenging for troops to maneuver and engage the enemy, with the side on the offensive usually at the disadvantage because the nature of their operations required greater mobility than the side fighting on the defensive, which could remain more stationary. For example, at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House in May 1864, a Mississippi private recalled: “Soon the Yanks made a determined charge with fixed bayonets, but the mud fought for us. Many of them were shot dead and sank down on the breastworks without pulling their feet out of the mud” (Cockrell and Ballard 1995). Besides the mud, wet weather could have a devastating effect on firearms, rendering them faulty or even inoperable in various military actions. In some engagements, pervasive wetness caused troops’ weapons to misfire, preventing them from offering serious resistance to their opponents. At Spotsylvania for instance, an attacking Federal force was able to overrun a salient in the enemy defensive line because many of the Confederates could not blunt the U.S. assault due to their rain-impaired muskets (Figure 3).

Facing such a wide range of problems, troops devised methods to combat wet weather, improvising and using any means available alleviate its difficulties. Some of these adaptions were simple. Men living in tents learned to dig small ditches around the perimeter of their shelters to prevent flooding, to securely stake their tents to withstand wind gusts, and to build makeshift beds using hay, brush, or other available materials to stay off the saturated ground. To make slogging through rain and mud easier, they learned to carry only the equipment that they considered the most essential for their survival. Others employed coping mechanisms to help mentally endure, such as swearing as an emotional release or distracting themselves through humor. Marching troops, for instance, made jokes and laughed in amusement as they watched comrades fall or get stuck in muddy roadways.

The material items typically issued to soldiers had a critical role in shaping their experiences with the weather. To these men, tents, uniforms, blankets, and other pieces of equipment were much more than just stuff. No matter the facet of wartime service, troops who possessed or had access to sufficient equipment often fared better when it came to adverse weather than those men who did not. In rainy conditions, soldiers hoped to possess the different types of waterproof blankets. Soldiers would lay on, cover their bodies with, or wrap the blankets around themselves while trying to sleep in camp, standing on guard duty, or marching through the rain (Gaede 2022). They were a versatile item that men never wanted to be without when the weather was bad. At a Mississippi camp in January 1863, Missouri (U.S.) Lieutenant Henry Kircher noted, “I wrapped myself in my rubber blanket and let it rain to its heart’s content without getting wet” (Hess 1983). Against the mud, there was no more important weapon than soldiers’ footwear. The standard shoe for infantrymen was ill-suited for rainy weather, allowing men’s feet to become soaked. Consequently, when storms raged and the ground became viscous mud, soldiers preferred to have high leather boots, which were much more water resistant. Infantrymen were not issued high boots and had to procure them on their own, with many writing home requesting that their families send them. No matter how they obtained boots, soldiers were appreciative for the protection and comfort they provided. After a muddy march in early 1863 in Virginia, New York Corporal John Hartwell contended, “I never had anything that did me more good or that I was more thankful for than those boots” (Britton and Reed 1997).

Through their struggles against rain as well as the heat and cold, Civil War soldiers generally became more successful at adjusting to the rigors of weather over the course of their service as they accumulated knowledge and experience across the varying terrain of the war. Adapting to the difficulties of weather helped men survive the conflict and turned out to be a critical element in how common soldiers became hardened veterans.

Bibliography

Jones, Olive, and Catherine Sullivan

1989 The Parks Canada Glass Glossary for the Description of Containers, Tableware, Flat Glass, and Closures. Studies in Archaeology, Architecture and History. National Historical Parks and Sites, Canadian Parks Service, Environment Canada.

Lindsey, Bill

2024 Historical Glass Bottle Identification & Information Website. Electronic document, https://sha.org/bottle/, accessed May 2024.

Lockhart, Bill, Bill Lindsey, Carol Serr, Pete Schulz, and Beau Schriever

2016 Manufacturer’s Marks and Other Logos on Glass Containers- L. Electronic document, LLogoTable.pdf (sha.org), accessed May 2024.

Lockhart, Bill, Nate Briggs, Beau Schriever, Carol Serr, and Bill Lindsey

2017 Laurens Glass Works. Electronic document, https://sha.org/bottle/pdffiles/LaurensGW.pdf, accessed May 2024.

McCarthy, Mary

2019 Sprite Delight: National Park Bottles. Electronic document, https://www.beachcombingmagazine.com/blogs/news/sprite-delight, accessed May 2024.

Miller, George L., Patricia Samford, Ellen Shlasko, and Andrew Madsen

2000 Telling Time for Archaeologists. Northeast Historical Archaeology poster series 29(1).

The Coca-Cola Company

2024 The History of the Coca-Cola Contour Bottle- The Creation of a Cultural Icon. Electronic document, https://www.coca-colacompany.com/about-us/history/the-history-of-the-coca-cola-contour-bottle, accessed May 2024.

Whitten, David

2024 Glass Bottle Marks. Electronic document, https://glassbottlemarks.com/, accessed May 2024.

The post Milk, Medicines, and Mammoth Cave? Let’s Talk About 20th Century Glass Bottles appeared first on Dovetail Cultural Resource Group, A Mead & Hunt COmpany.

“Hens’ Teeth” Found in Delaware: North Devon Gravel-Tempered Ware in Delaware By Lee Priddy and Bill Liebeknecht 18 Apr 2024, 5:04 pm

Photo 1: North Devon Gravel-Tempered Milkpan Rim Sherd from the Chesapeake Region.

By Lee Priddy and Bill Liebeknecht

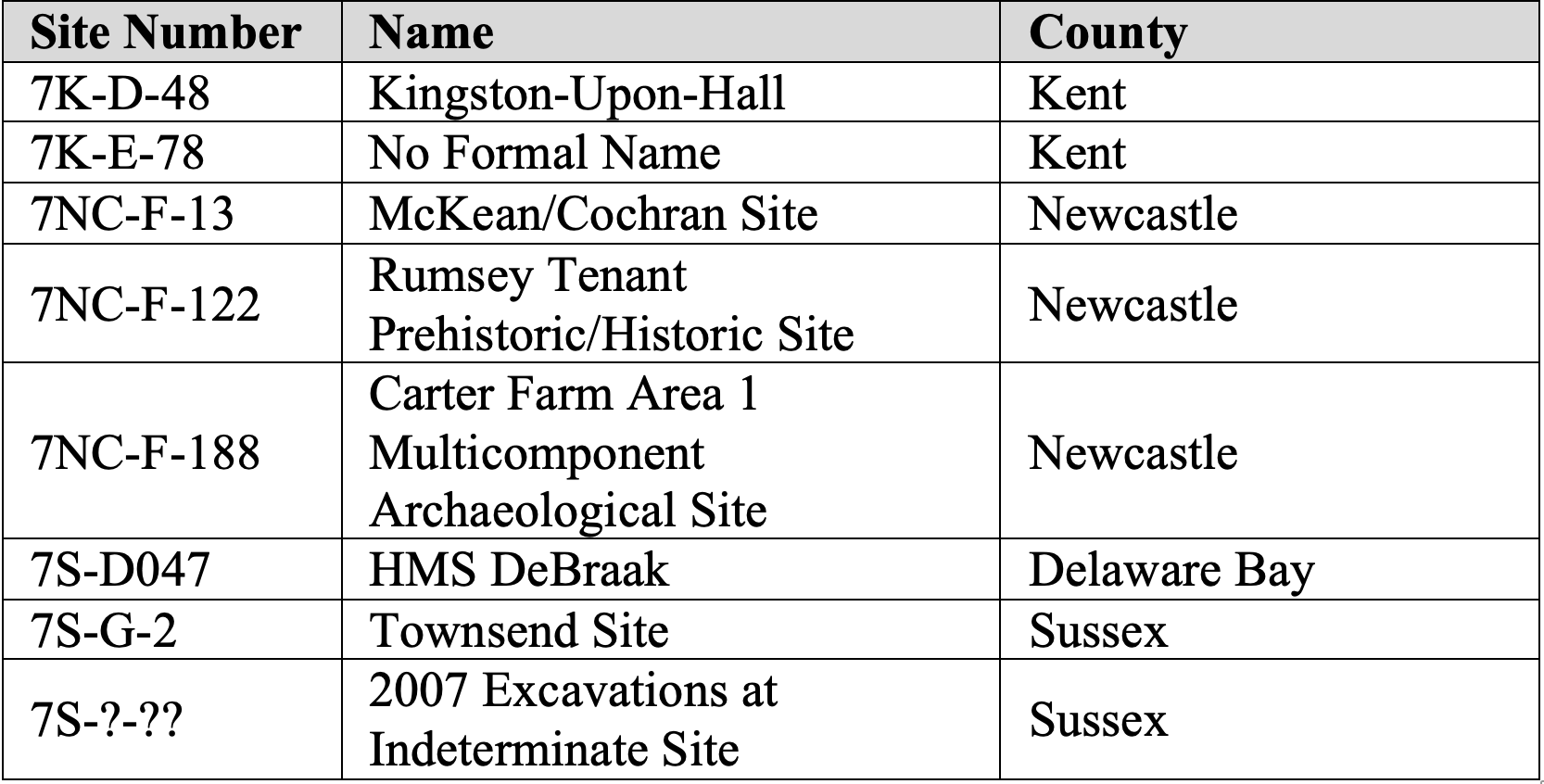

One of the more common types of ceramic found on early historic American archaeological sites is a ware called North Devon gravel-tempered earthenware (Photo 1). It is frequently encountered on archaeological sites in the Chesapeake region and in New England, but fragments are rare on colonial sites in Delaware. The question is, why? To answer this question, researchers have been examining professional and avocational archaeological collections in Delaware for these elusive wares with limited success. To date, North Devon gravel-tempered ware has only been reportedly found on eight archaeological sites throughout Delaware. The most recently recovered sherd of North Devon gravel-tempered ware was identified at the Carter Farm Area 1 Multicomponent Archaeological site (7NC-F-188) during a Phase IB archaeological survey performed by Dovetail Cultural Resource Group in partnership with South River Heritage Consulting.

North Devon wares originated from the North Devon area of western England, consisting of the towns of Barnstaple, Bideford, and Great Torrington. This utilitarian earthenware, typically used to make plates and trenchers, was exported in great numbers to the American colonies and can be further separated into three ceramic ware types: North Devon Sgrafitto, North Devon gravel-tempered, and North Devon gravel-free. North Devon Sgrafitto is characterized by incised slip decorations (where white kaolin clay is poured over red clay before firing and scratched through both layers to form a design) and dates from the 1620s through the end of the seventeenth century in the Chesapeake region. North Devon gravel-tempered ware was manufactured from 1600 through the nineteenth century. It was available in the Chesapeake region from circa 1650 through the first quarter of the eighteenth century. It is characterized by a yellow to brown, translucent lead glaze and the presence of pieces of large gravel in the body of the ceramic that was added to stiffen the clay to product larger vessels such as milk pans, washtubs, food storage vessels, butter jars, and even small ovens. Finally, North Devon gravel-free ware exhibited the same yellow to brown, translucent lead glaze but did not contain the addition of gravel. It has been found in the Chesapeake in pre-1635 contexts through the early eighteenth century (Grant 1983:53–62; Maryland Archaeological Conservation Lab 2015; Noël Hume 1991:104–105, 133–134; Pittman 1997; Watkins 1960:40, 45, 47).

Historical research of the colonial trade routes in Delaware leads to more questions. Delaware had close economic ties with Bristol, England—a city with close connections to the ceramic production centers at Barnstaple and Bedford. However, there is no record of the direct export of North Devon pottery from Barnstaple or Bideford to Delaware. Port record books show no evidence that earthenwares from the North Devon area of England were shipped out of Boston to New York or New Jersey, which had their own pottery centers. Could that explain why North Devon gravel-tempered ware is not more prevalent in archaeological collections from Delaware? The few sherds of North Devon gravel-tempered ware identified from sites in Delaware appear to date later into the eighteenth century, in direct contrast to the Chesapeake region (Fithian n.d.:1–2; Grant 1983:24–27; Watkins 1960:125) (Table 1).

Table 1. Delaware Site with Reported North Devon Gravel-Tempered Ware (Data gathered from the Delaware Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs and Gall et al. 2018).

In May 2023, Phase I archaeological survey at Carter Farm Area 1 Multicomponent Archaeological site (7NC-F-188) recovered a single sherd of North Devon gravel-tempered ware from the surface of the plow zone (Bianchi et al. 2023:50, 53). The sherd is a wheel-thrown flat ceramic vessel with classic gravel temper and greenish-brown lead glaze on its interior (Photo 2 and Photo 3). This domestic site has been tentatively dated from the late-seventeenth or early-eighteenth century to circa 1780. Other early ceramic types recovered from the site consist of Buckley ware, Westerwald stoneware, tin-glazed earthenware, and dipped white salt-glazed stoneware. These ware types coincide with the prescribed date range for North Devon gravel-tempered wares, suggesting the identification of this sherd is accurate.

Photo 2: Interior Surface of North Devon Gravel-Tempered Body Sherd from 7NC-F-188.

Photo 3: Exterior Surface of North Devon Gravel-Tempered Body Sherd from 7NC-F-188.

Although North Devon gravel-tempered earthenware is rarely observed on archaeological sites in Delaware, a closer examination of the collections stored at the Delaware State Museum may reveal it is more plentiful than we are currently aware. Redware and pale-bodied earthenware are often lumped together and overlooked in archaeological collections, so this ware type could be easily misidentified, even with its distinctive gravel tempering. With its prevalence in the Chesapeake region, Colonial-era sites along the southern and western borders of the state may hold a higher potential to find North Devon gravel-tempered ware as it would have been shipped up the Chesapeake Bay, which borders Delaware. Sites dominated by redware need to be examined carefully to ensure that North Devon gravel-tempered earthenware is not overlooked. Future fieldwork at Carter Farm Area 1 Multicomponent Archaeological site (7NC-F-188) coupled with additional historic research may help answer why North Devon gravel-tempered ware is as rare as hens’ teeth in Delaware. It is hoped that planned Phase II testing at the site on Carter Farm will provide additional information on this obscure ware type in Delaware.

Bibliography

Bianchi, Lucia, Andrew Martin, Lee Priddy, and Bill Liebeknecht

2023 Phase IB Archaeological Survey of Carter Farm in Middletown, Pencader Hundred, New Castle County, Delaware. Dovetail Cultural Resource Group, Fredericksburg, Virginia.

Gall, Michael, Ilene Grossman-Bailey, Philip Hayden, and Adam Heinrich

2018 Living on the Boder; Phase II Archaeological Survey and Phase III Archaeological Data Recovery – Locus 1 of the Rumsey/Polk Tenant/Prehistoric Site (7NC-F-112, CRS # N-14492). Richard Grubb and Associates, Cranberry, New Jersey.

Grant, Alison

1983 North Devon Pottery: The Seventeenth Century. The University of Exeter, Exeter, England.

Fithian, Charles

n.d. North Devon Earthenwares in Delaware. Electronic document, https://apps.jefpat.maryland.gov/diagnostic/ColonialCeramics/Colonial%20Ware%20Descriptions/North%20Devon%20Gravel%20tempered%20final%20.pdf, accessed April 2024.

Maryland Archaeological Conservation Lab

2015 Ceramics in Maryland. Diagnostic Artifacts in Maryland. Electronic document, https://apps.jefpat.maryland.gov/diagnostic/index-Ceramics.html, accessed March 2024.

Noël Hume, Ivor

1991 A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America. Reprint of 1969 edition. Random House, New York, New York.

Pittman, William

1997 Lee Priddy original unpublished lecture notes from Fall 1997 Introduction to Historical Archaeology class (HIST 607), lecturer William Pittman, Colonial Williamsburg Department of Archaeological Research, College of William & Mary, in Williamsburg, Virginia. Manuscript on file at Dovetail Cultural Resource Group, Fredericksburg, Virginia.

Watkins, C. Malcolm

1960 North Devon Pottery and its Export to American in the 17th Century. Bulletin 225, United States National Museum, Washington D.C.

The post “Hens’ Teeth” Found in Delaware: North Devon Gravel-Tempered Ware in Delaware By Lee Priddy and Bill Liebeknecht appeared first on Dovetail Cultural Resource Group, A Mead & Hunt COmpany.

Celebrating Virginia Archaeology: The City is Digging the New Archaeological Ordinance! 15 Mar 2024, 3:11 pm

By Adriana Moss

Fredericksburg has a wonderfully rich occupation spanning thousands of years. However, when it comes to historic tourism, efforts have commonly focused on the city’s prominence during the Civil War, maybe a little bit of our role in early colonial commerce, and as the home of Mary Washington, the mother of the first President of our country. Lately, with the support of our State Historic Preservation Office (the Virginia Department of Historic Resources), the focus in many localities within the Commonwealth has shifted to tell a fuller and more inclusive story than the written record tends to provide. What better way to do that than through archaeology, where we have the ability to expand our knowledge of a place and its occupants in ways that no other forms of research or study can? Enter the Fredericksburg “Archaeology Preservation District” in the Unified Development Code (City Code 72), or more commonly referred to as the Archaeological Ordinance, passed in 2021. Dovetail Cultural Resource Group (Dovetail) was selected as a City archaeological consultant shortly thereafter to help with projects completed under the new law.

For more than a decade, goals had been set forth by the City to incorporate archaeological considerations into land development projects citywide within several iterations of Comprehensive Plans and City Council Priorities. According to Kate Schwartz, the City’s Preservation Planner, the regulations and district were developed by multiple working groups, namely the archaeology working group established in 2017, that researched “best practices and sample ordinances, consult[ed] with cultural resource professionals, and conduct[ed] an evaluation of the City’s archaeological potential.” Dovetail president Kerri Barile Tambs was honored to participate in this working group. Several digs within the city, such as at the Marriott site complete in 2006, uncovered more than 300 years of layered occupational history. This site in particular included artifacts and foundations of eighteenth-century stores, the Indian Queen Tavern, and nineteenth-century servants’ quarters and alley walls. When the ordinance was drafted nearly 15 years later, it was important to the City to bring in members of the local development and building community to be a part of the conversation, according to former Councilman Matt Kelly, noting that “it is a very successful model when the people who are impacted are in the room and provided a voice.” When asked about any successes or challenges the ordinance has posed thus far for applicants, Schwartz stated that the expectations of property developers and general standards outlined in the ordinance are clear, which “has been extremely helpful in working through various review processes.” “Impacts to archaeological resources are evaluated for all applications received for certificates of appropriateness (COA), major site plans, minor site plans, and residential lot grading plans,” according to Schwartz.

“Impacts to archaeological resources are evaluated for all applications received for certificates of appropriateness (COA), major site plans, minor site plans, and residential lot grading plans,” according to Schwartz.

The ordinance was scheduled to take effect in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, but was not enacted fully until FY22 (July 1, 2021–June 30, 2022). Within the first two years, 148 COAs have been reviewed; in addition, 16 major site plans, 18 minor site plans, and 248 residential lot grading plans were approved. Schwartz maintains that “Phase I [also known as reconnaissance-level] studies associated with new residences have been most common and have provided a unique opportunity for study in historic neighborhoods that are largely developed,” while other types of archaeological study have included monitoring, such as during grading activities for the new Idlewild Middle School. Up to this point, Schwartz says, “the skew toward Phase I studies over monitoring […] was not something we predicted, but it seems to be working well. If the trend continues, it may be something worth formalizing in an amendment to the code in the future. I think in general; we will need several more years of observation before we can clearly identify trends or potential modifications.” Kelly agrees with this sentiment, stating that the ordinance should be reviewed every several years to reevaluate the processes and address other areas of concerns such as general collections management of artifacts uncovered as well as their accessibility to the public and researchers.

According to Schwartz, the findings to date have been important to our body of knowledge but have not stopped planned projects. “I’m grateful for knowing we have the ability and authority to investigate and document, to some level, of essentially any development in the City. It gives us the ability to be proactive rather than reactive; and if we do need to be reactive, we have a ready structure and process that we can implement,” states Schwartz. One project in particular, a Phase I survey at 1416 Princess Anne Street, shed light on a notable Jim Crow-era African American-owned boarding house. Completed by Dovetail, the work demonstrated how “archaeology is often the tool most suited to learning about underrepresented history in our city: African American residents, immigrants, those of modest means, and others. The studies we’ve done and will continue to do give us a much more thorough picture of life in the city.” Kelly adds that “the human story is something that fascinates everybody [and] archaeology gives us that opportunity to tell so many more stories. There is a lot of stuff that we [will] find that will change the understanding of the history of the city.”

Dovetail archaeologists dig the Hieskell-White Site on Sophia Street. This development, sponsored by Tommy Mitchell, was a test case of the new ordinance (Dovetail 2020).

Dovetail Vice President and Archaeologist, Mike Carmody, Providing a Tour to Local School Group at the Marriot Site (Dovetail 2006).

Tim Duffy, current Fredericksburg City Counciler, and former Dovetail Archaeologist, Brad Hatch, Discussing Pottery Found at the Riverfront Park Excavation (Dovetail 2019).

Author Cleaning Exposed Ice House Wall at Riverfront Park Excavation (Dovetail 2019).

John Hennessy, former Chief Historian at the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park (left), Matt Kelly (center), and former Dovetail Archaeologist, Earl Proper, at the Marshall-Bell Kiln Site (Dovetail 2013).

The post Celebrating Virginia Archaeology: The City is Digging the New Archaeological Ordinance! appeared first on Dovetail Cultural Resource Group, A Mead & Hunt COmpany.