Add your feed to SetSticker.com! Promote your sites and attract more customers. It costs only 100 EUROS per YEAR.

Pleasant surprises on every page! Discover new articles, displayed randomly throughout the site. Interesting content, always a click away

Job Posting – Project / Construction Manager 5 May 2016, 3:11 pm

PROJECT / CONSTRUCTION MANAGER POSITION

Urban One is currently seeking to fill a Project Manager position. Applicants should view the following job posting for more information:

Company: Urban One

Location: Los Angeles, CA

Job Type: Project / Construction Manager (1099 Independent Contractor)

Deadline: May 20, 2016

Hours: Full Time – 40hrs/week (minimum)

Company Description: Urban One is a boutique Los Angeles based firm that specializes in the development and management of complex urban real estate projects for its own acquisitions, as well as for other property owners in a consulting capacity. We are passionate about real estate projects that create lasting change in communities. Our firm has a strong track record that has our reputation as problem solvers. Our projects are typically complex, controversial, and/or involve numerous, often competing interests. Learn more about Urban One at www.urbanone.com.

Notable current and future projects are:

- Redevelopment of an existing 90,000 sf shopping center in mid-city LA.

- Retail construction consulting and tenant coordination for a high-profile mixed-use (student housing over retail) project at the largest private university in LA.

- Acquisition and redevelopment of an existing 2,600 sf single-family home in Playa del Rey.

- On-call development/construction management and tenant coordination services for various shopping centers located throughout Southern Cal for a national public retail REIT.

- Mixed-use (creative office over retail) adaptive reuse project of historic building in downtown LA.

- New 125+ bed senior-housing/assisted-living development located just outside of LA.

Duties:

The candidate will manage and oversee many aspects of the firm’s projects, including:

- Development & Construction Management: being the main point of contact for the company and capable of managing all aspects of the project(s) to ensure project(s) meets budget and schedule requirements, including, but not limited to, selection and management of all consultants; consultant contract negotiations; design coordination; estimating and budgeting; preparation of RFP’s and running contractor bid process; scoping/bid comparisons; value engineering; preparation of contracts; general contractor contract negotiations; preparation of schedules; coordination with City agencies to obtain permits and approvals; oversee general contractor and all consultants during construction process and run weekly meetings onsite; briefing of clients on progress; RFI & Submittal oversight; document control; change order review and processing; tracking of all project financials via cost report; pay application/invoice review; project closeout and punchlist.

- Tenant Coordination: if need be, having the ability to occasionally act as a tenant coordinator on commercial projects, including, but not limited to, LOI/Work Letter review; interaction with tenants, as well as tenants’ design team and contractor; review of tenant improvement drawings; tenant allowance review and processing; ongoing coordination throughout TI process.

Mandatory Qualifications:

Candidates applying for the position should have the following minimum qualifications:

- Bachelor’s and/or Master’s degree in the area of Construction Management or Real Estate Development.

- Confident and capable of managing projects on their own with very limited direction.

- Highly motivated, resilient, organized and self-directed individual capable of taking on all facets of project management.

- Entrepreneurial and able to work in a small business environment.

- Ability to verbalize concepts and effectively pitch the company’s goals and services.

Preferred Qualifications:

- Proficiency in MS Office, including MS Project.

- Approximately 7-10 years of experience in construction management and/or real estate development.

- Experience with retail development is a plus.

- Experience with multi-family and/or senior-housing is also a plus.

Compensation/Benefits:

Depends on experience. Note that this position will be a 1099 independent contractor/consultant and not a W2 employee, so no benefits will be offered by Urban One at this time.

Applicant Submission: Please submit resume to jobs@urbanone.com (please include the subject line “Application – Project Manager Position” in the subject) or contact your local representative where this posting was listed.

Click here for a printable version of this job posting:

2016 Urban One Project Construction Manager Job Posting

The post Job Posting – Project / Construction Manager appeared first on .

Building a Better Density Bonus, Part 5: A Revolution in Affordable Housing Provision 8 Jun 2015, 10:27 pm

This is Part 5 of a five-part series by Urban One, which outlines recommendations and proposals for improving the California/Los Angeles density bonus program. Part 1 focused on background, while Parts 2 through 5 include specific recommendations to improve the density bonus and affordable housing provision throughout the region.

In our Building a Better Density Bonus series we’ve covered a range of concepts and recommendations for increasing the amount of affordable housing in Los Angeles at minimal public cost, but we’ve saved the most innovative (and, in our opinion, best) idea for last.

Generally speaking, what we’ve talked about so far is how to create more affordable housing from new construction. In a city with over 850,000 renter-occupied housing units, however, we’re missing a huge opportunity by focusing almost exclusively on the approximately 15,000 new units built each year (most of which will necessarily be market-rate anyway). What if we opened up our existing housing stock for use as affordable housing?

Done right, we can use the density bonus to increase the supply of market-rate housing while also raising funds to subsidize affordable units in existing multifamily buildings—all at much lower cost than the current new-construction-only regime.

Proposal: Create an alternate fee-based density bonus program; use these funds to subsidize units in less expensive market-rate buildings.

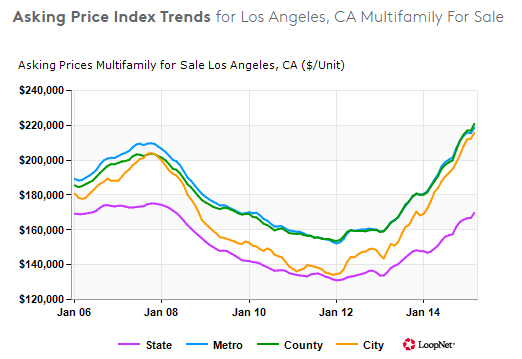

According to data from 2011, the average cost of new affordable units peaked in California in 2009, at $334,000 per unit, and fell to $260,000 by 2011; due to rising land values and construction costs, the current cost of affordable unit production in LA is likely greater than $350,000 per unit. By comparison, the median asking price for a multifamily unit in Los Angeles is currently under $220,000.

To take advantage of this cost disparity, Los Angeles should develop a program to acquire older (but still safe and livable) multifamily units with fees paid in lieu of on-site construction of affordable housing. Instead of providing on-site affordable housing at $300,000 or more per unit, developers could pay into a fund—say, $200K-$250K, or even higher for more expensive projects—that would subsidize a greater number of affordable homes in nearby, currently market-rate buildings.

This program would have a number of benefits:

1. Density bonus developments would create more total affordable housing—potentially much more, depending on how the fee is structured—by spending in-lieu fees on less expensive properties.

2. If the fee is reasonable it should encourage increased participation in the density bonus program, further increasing the supply of both affordable and market-rate units at no public cost. This program would be especially appealing to smaller-scale developers (10 to 50 units) for whom the hassle and cost of managing just a few affordable units often exceeds the value of additional market-rate units.

3. By buying new units outright, the city (or its agent) could hold these properties in perpetuity. Affordable units are currently covenanted for 55-years in California, at which point they revert back to market-rate—that would not be necessary under this proposed program.

4. Because these acquisitions are permanent, they become an asset that can support additional affordable housing acquisition/conversion in the future. With minimal support this program could become relatively self-sustaining and grow exponentially: one paid-off building can support the acquisition of several more developments, each of which can support even more acquisitions as they are paid off, on and on, forever.

To be clear, this is not an entirely new idea, it’s just a good one: The Connecticut Housing Finance Authority launched an initiative a few years ago to provide favorable financing to investors who wanted to purchase or refinance existing market-rate developments, as long as they convert a share of them to affordable housing. Largely funded by federal HUD grants, the Zollie Scales Manor apartments in Houston were renovated and made affordable to households earning less than 80 percent of area median income. Drawing from a variety of funds, including in-lieu density bonus fees, Los Angeles could implement a similar program on a much grander scale.

IMPLEMENTATION

Because an acquisition-based affordable housing strategy would be such a dramatic departure from current policy, a range of implementation issues would have to be addressed.

Equity

For one, it would be important to structure the program so that it increased the total supply of both affordable and market-rate housing. Without such a framework in place, we’d be dealing in zero-sum trade-offs in which every new affordable home is one less market-rate unit; as more low-income renters gained access to affordable housing, the pressure on market-rate units would increase and drive rents ever higher for middle income Angelenos. This is where the density bonus comes in handy: by allowing for an in-lieu fee program, funding for the acquisition of existing buildings and conversion to affordable housing is directly tied to the production of housing beyond existing zoning limits.

It would also be important to ensure that units purchased with density bonus fees were in close proximity to the new developments that produced those fees, to avoid creating islands of poverty. In most cases this should not be difficult to achieve, since development in LA has been focused in relatively densely-populated neighborhoods with plenty of existing housing stock—places like Hollywood and Koreatown in particular.

Financial

It might be desirable to purchase entire buildings but set aside only a share as affordable to further prevent concentration of poverty at the individual building level; the market-rate units in such a building would also help to further subsidize the affordable units. Using a quick and dirty financial analysis, we examined a hypothetical building purchased for $250,000 per unit, setting aside 20 percent of its units for low income residents, at rents of $800 a month. We assumed that in-lieu fees would be used to support this venture by paying down loan interest costs in early years, reducing the effective interest rate from 5 to 2 percent, with market-rate units contributing a larger share of interest payments over time.

We found that, in a 100-unit building with an average market-rate rent of $1,500 and 20 percent of units rented to low income families at $800 a month, $500,000 in in-lieu fee subsidies would be required in year 1, shrinking to $400K by year 7 and $300K by year 10. By year 18, the building would be completely self-sustaining, having received a total subsidy of $5.5 million*—all of which is derived from in-lieu fees paid by private developers. In the years that followed, the property would continue throwing off revenues that could subsidize additional acquisitions and interest payments for other affordable properties. At the conclusion of the 30-year loan term, the property could be refinanced for major capital expenditures (including renovation), or simply use its annual profits to continue subsidizing an ever-greater number of affordable units in the city. Rather than allowing the long-term value of these properties to be captured by private owners, it would be retained by community members in the form of a balanced supply of mixed-income housing. Traditional affordable housing grows less valuable to the public over time, as the years run out on their covenants and they prepare to be converted back to private, market-rate use. Properties acquired and managed under this new program, by comparison, would only increase in value as their loans were paid off and revenues were used to reinvest in other affordable housing projects.

Governance

Developing a governance structure that was free of political influence and insulated from the local government to the greatest degree possible would be extremely important for a program of this nature. Property acquisitions and management could be handled by a economic development corporation or other non-governmental organization, for example, with the local government serving primarily as a pass-through for affordable housing funds. This would shield the public sector from getting too directly involved in private real estate market interventions, and would allow operational decisions to be made with minimal political interference. Ideally, it would also ensure that the short-term thinking endemic to many political groups did not affect the long-term mission and vision of the non-profit housing organization.

Being the most complex proposal of our Building a Better Density Bonus series, creating a program like this would undoubtedly be a major undertaking. That said, in an era where our approach to affordable housing is often piecemeal, inconsistent, and woefully inadequate, this serves as a counterpoint with the potential to be truly transformational. We hope LA leaders will seriously consider its implications, and we’re happy to join the conversation and see what can be done to increase the supply of affordable housing in our city!

Thanks for reading!

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5

*We should also note that this analysis is very conservative, assuming market-rate rents increase at just 3 percent a year and that affordable rents remain essentially unchanged throughout the 30-year period, and that in-lieu fees are the only financial subsidy offered to the project—in truth, it’s entirely possible that such a program could also secure any number of grants, incentives, and rebates, all of which would further reduce direct subsidy costs to the city.

Note: It is not our intent that the ideas/recommendations included in this series be interpreted as ideal solutions to our city and state’s affordable housing problems. Rather, in the spirit of the LABC Institute’s recent report, we hope to foster engagement and debate about this important subject, and to begin the process of a transition toward more effective and efficient programs that better serve the needs of all LA residents—especially those with limited incomes who suffer the most from a lack of affordable housing. There are undoubtedly a variety of legal and procedural barriers to many of these ideas; some of those are in place for good reason, others may not be and should be reconsidered. Also please note that the ideas in this series are presented on behalf of Urban One and do not necessarily reflect to ideas, recommendations, or values of any other individual or organization.

We invite readers to share their comments and their own ideas for how we might improve the provision of affordable and market-rate homes, implementation ideas and tweaks to the ideas presented here, or case studies of similar successful programs in other cities and countries.

The post Building a Better Density Bonus, Part 5: A Revolution in Affordable Housing Provision appeared first on .

Building a Better Density Bonus, Part 4: Making the Most of Neighborhood Upzones 3 Jun 2015, 9:01 pm

This is Part 4 of a five-part series by Urban One, which outlines recommendations and proposals for improving the California/Los Angeles density bonus program. Part 1 focused on background, while Parts 2 through 5 include specific recommendations to improve the density bonus and affordable housing provision throughout the region.

With our previous proposals in Part 2 and Part 3 we’ve focused on modifications to the existing density bonus law. For this one, we go in a slightly different direction. We’re going to look at some recent specific plans in LA—one implemented, one currently in draft form—that, while not technically a part of the density bonus program, operate in a similar way.

These plans are largely dependent on capturing the increased land values that accompany “upzones”—that is, changes to zoning that allow for increased development potential within a neighborhood—and are not as applicable outside of this context. Upzones are a fairly common occurrence, however, so it’s worth exploring how we can make the most of them to increase equity and provide additional community resources. The affordable housing incentives in these plans can also be seen as a sort of “density bonus on steroids,” and so the connection between this and the proposal in Part 2 should become clear as we move along.

So with that background in mind, let’s move on to proposal 3!

Proposal: Capture value of increased development potential in upzoned neighborhoods.

Of the two plans we wanted to look at, the Cornfield Arroyo Seco Specific Plan (CASP) is probably most familiar to readers. CASP was adopted fairly recently and it includes a number of provisions and requirements related to unit density, floor-area ratio (FAR), commercial vs residential uses, etc., but for our purposes we’ll just focus on the affordable housing options discussed in the Zoning and Standards section.

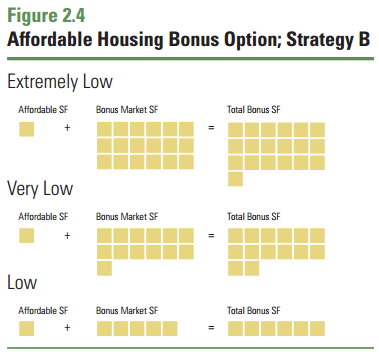

There are actually two options available to take advantage of the density bonus outlined in CASP, but one—Strategy B—seems much more viable from a developer’s perspective. (Note that we are not experts on CASP and it’s entirely possible that we’re misinterpreting the implementation process for Strategy A. There are also nuances we will deliberately overlook to simplify the explanation.) As mentioned above, this affordable housing option is something like a “density bonus on steroids,” allowing the developer to build up to 4.0 FAR in certain “Urban Village”-designated areas—a more than 150 percent increase over the base 1.5 FAR. This means that, with a share of its units set aside as affordable housing, a 50,000 square-foot (SF) plot of land could be developed up to 200,000 rather than 75,000 SF. That means more affordable and market-rate housing for local residents.

Specifics aside, the reason that neighborhoods like CASP can put exceptional requirements on new construction is that those requirements are coupled to significant increases in development potential. That development potential has financial value, and so while the city gives with one hand (upzoning) it takes with the other (additional development requirements). As long as the value of the upzoning exceeds the cost of those new requirements, everyone wins. The owners get a little bit more money—but not a windfall—and the community is able to capture most of the increase in value in the form of affordable housing, open space, transportation improvements, and other local amenities.

A similar program—the Exposition Corridor Transit Neighborhood Plan (ECTNP)— is underway in Phase II Expo station neighborhoods all the way to West LA. Like the CASP, the Expo Corridor plan includes a range of public benefits that must be provided in order for developers to build to the new maximum heights, FARs, etc. Also like the CASP, affordable housing is a major component of this specific plan.

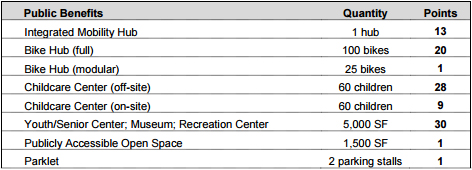

The ECTNP differs from CASP in that it seems more straightforward and easy to interpret. Rather than having a variety of paths and strategies for taking advantage of the new FAR limits, every developer in the Expo corridor neighborhoods must follow essentially the same path: First, all new developments are required to include some baseline set of public benefits, including basic streetscape improvements, unbundled or otherwise better-managed parking, open space, and so on—these are required to build anything, regardless of FAR. To receive an intermediate density bonus, developers must provide any of a number of more expensive public benefits, including extensive streetscape improvements, publicly-available open space, mobility hubs, and so on. The quantity of public benefits to be provided is determined by the extent of private development, with a simple point system in place to make the calculations easy for developers to understand and plan for. More development means more public benefits, which is a great strategy for getting local communities on board with new growth.

To receive the full density bonus, which can amount to as much as an 85 percent increase over the intermediate FAR limits, affordable housing must be provided. Twenty percent of all residential units must be affordable to low income residents (up to 80 percent of area median income), compared to up to 20 percent of pre-bonus units for traditional density bonus projects. In this respect, the requirement is more stringent than the citywide density bonus. Again, the value of the added development potential is what makes this policy workable. Why give away the added value for free, right?

As the city continues to evolve and new areas open up for rezoning and redevelopment, finding more ways to make the most of these value capture mechanisms—not just improving financial returns, but also making participation as straightforward and easy to understand as possible—should be a priority. It’s clear that city planners already have this in mind, and hopefully more attention can be brought to these plans, with more stakeholders working to make them as effective and streamlined as possible.

That’s a wrap on Part 4! We’ve saved the best for last in this series, so stay tuned for Part 5 of Building a Better Density Bonus! It involves a completely new approach to the density bonus that has the potential to dramatically reshape how we provide affordable housing in our city. It could also be a much more sustainable way to provide affordable housing, with a long-term growth strategy and permanent affordability restrictions rather than the limited-duration covenants in place for most subsidized housing available today. Coming soon!

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5

Note: It is not our intent that the ideas/recommendations included in this series be interpreted as ideal solutions to our city and state’s affordable housing problems. Rather, in the spirit of the LABC Institute’s recent report, we hope to foster engagement and debate about this important subject, and to begin the process of a transition toward more effective and efficient programs that better serve the needs of all LA residents—especially those with limited incomes who suffer the most from a lack of affordable housing. There are undoubtedly a variety of legal and procedural barriers to many of these ideas; some of those are in place for good reason, others may not be and should be reconsidered. Also please note that the ideas in this series are presented on behalf of Urban One and do not necessarily reflect to ideas, recommendations, or values of any other individual or organization.

We invite readers to share their comments and their own ideas for how we might improve the provision of affordable and market-rate homes, implementation ideas and tweaks to the ideas presented here, or case studies of similar successful programs in other cities and countries.

The post Building a Better Density Bonus, Part 4: Making the Most of Neighborhood Upzones appeared first on .

Building a Better Density Bonus, Part 3: Leveraging Public Funds to Maximize Private Investment 28 May 2015, 5:34 pm

This is Part 3 of a five-part series by Urban One, which outlines recommendations and proposals for improving the California/Los Angeles density bonus program. Part 1 focused on background, while Parts 2 through 5 include specific recommendations to improve the density bonus and affordable housing provision throughout the region.

In the last installment we discussed our first recommendation for density bonus reform: Reducing the affordable unit requirement for individual projects, and tying this change to clawback provisions on development projects that exceed profit expectations. The underlying rational for this recommendation is that, for every developer who chooses not to participate in the density program (or doesn’t take full advantage of it), the city is losing out on hundreds of thousands—even millions—of dollars in private investment in affordable housing. Lowering the threshold for participation may decrease the value of this investment on a per-project basis, but total private investment will increase as more projects participate in the density bonus program.

Our next proposal builds upon this idea, recognizing that, for many developers, participation in the density bonus program is a marginal decision—that is, relatively small amounts of money often make the difference between constructing the maximum number of affordable units or constructing none at all. This is something of an “in for a penny, in for a pound” situation, where if you’re willing to go through the density bonus process, you might as well go for the whole bonus in order to spread out your land costs over the largest number of units possible. Providing financial incentives to push developers toward the “build the maximum number of units” side of the ledger can, in some circumstances, be a low-cost means of increasing the supply of affordable housing, and should be considered when other options fall short.

Proposal: Fill funding gaps in density bonus project budgets with public sector funds, when necessary, to maximize private investment.

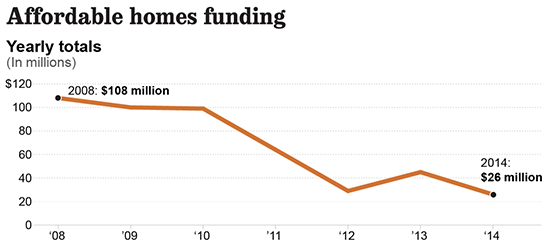

According to the Housing and Community Investment Department of Los Angeles (HCID), the city’s Affordable Housing Trust Fund allocation has fallen 75 percent since 2008, from $108 million to just $26 million per year, largely as a result of the dissolution of CRA and declining federal funds for low-income housing. The number of affordable homes that can be funded by the department has similarly declined, from 1,200 to approximately 250 units per year—far, far below the anticipated need of 82,000 new affordable units by 2021. That $26 million, at 250 units per year, means that HCID is spending an average of about $100,000 per unit, leveraging that investment to secure the remainder from other government and private sources. Not to disparage HCID, but we think it may be possible to leverage that money even further by filling gaps in projects that would like to participate in the density bonus, but can’t quite afford to.

If a developer’s financial analysis shows that the profit earned on bonus market-rate units can cover just $300,000 of the $350,000 cost of each affordable unit required to receive the bonus, for example, they probably will not build those affordable units. (Like any other business, developers that knowingly commit to money-losing ventures will probably not be in business for very long.) In such cases, the city should consider how it can help fill that gap and lay claim to the $300,000 of private investment that the developer can support. This may irk some individuals who consider this a giveaway to private developers, but the alternatives are far less appealing: using the same public funds to build the units at their full $350,000 cost*, or using them to leverage a very limited amount of state and federal Low Income Housing Tax Credit dollars. Spending $50,000 or less subsidizing affordable density bonus units would effectively double the leverage ratio of city housing expenditures and get us twice as much affordable housing for the money.

In a recent conversation with Allan Kotin, it was pointed out that low interest rates may also be playing a role in the limited density bonus participation of recent years. Under the 80/20 Housing Program, developments with at least 20 percent of their units devoted to low-income residents can receive tax-exempt financing. During the years prior to the housing crash, when interest rates were significantly higher, that tax exemption could knock a few points off the effective interest rates paid by the borrower. Today, with rates at all-time lows, the economic benefit of tax-exemption is much lower. Building off of Mr. Kotin’s observation, we suggest that it’s possible this effect could be offset by direct support from local cities, counties, or the state, allowing them to subsidize a larger share of the project’s financing costs in return for construction of affordable units.

There are a number of potential funding sources for these subsidies aside from the Affordable Housing Trust Fund. The state has dedicated a significant share of its cap-and-trade revenues to funding transit-oriented affordable housing, including upwards of $200 million expected to be raised in 2015; with about 1/10th of the state population and a high poverty rate, Los Angeles will likely be eligible for at least $20 million from that fund on an annual basis. The city could also offer property tax rebates to density bonus projects with a financial gap, just as they do with hotel subsidies. The upshot to a program like this is that it would require no up-front public expenditures: The developer would build the project with a promise from the city, and only if the anticipated financial gap were borne out would we pay them back with a break on their property tax bill. If the project was more profitable than expected, the property tax break could disappear entirely.

Any program—not just the property tax exemption—could implement controls and clawback mechanisms to recover excessive affordable housing subsidies. Just as with the reduced threshold program proposed in Part 2, if the city contributes $50,000 per affordable unit to fill a financial gap, they can recover those funds from the developer’s profits beyond a certain threshold. The up-front subsidy in all of these examples represents the most that the city would end up paying to subsidize each unit; if the project is more successful than expected, the total subsidy could decline to essentially nothing. Regardless of the developer’s financial outcome, the city increases its supply of affordable housing at minimal public cost.

By taking a comprehensive approach to funding affordable housing, it should be possible to better leverage limited public funds and have a greater share of our affordable housing built with private investment, “buying” affordable units for $50,000 each, or even less. With our next recommendation, in Part 4, we’re headed in a slightly different direction and looking at some recent neighborhood plans that have taken advantage of rezonings, using them to capture new value for the community and potentially provide a significant increase in privately-funded affordable housing.

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5

*The $350,000 affordable unit cost is assumed for illustrative purposes. Although it is a rough approximation of the current average unit cost for affordable housing, the actual cost can vary significantly between projects.

Note: It is not our intent that the ideas/recommendations included in this series be interpreted as ideal solutions to our city and state’s affordable housing problems. Rather, in the spirit of the LABC Institute’s recent report, we hope to foster engagement and debate about this important subject, and to begin the process of a transition toward more effective and efficient programs that better serve the needs of all LA residents—especially those with limited incomes who suffer the most from a lack of affordable housing. There are undoubtedly a variety of legal and procedural barriers to many of these ideas; some of those are in place for good reason, others may not be and should be reconsidered. Also please note that the ideas in this series are presented on behalf of Urban One and do not necessarily reflect to ideas, recommendations, or values of any other individual or organization.

We invite readers to share their comments and their own ideas for how we might improve the provision of affordable and market-rate homes, implementation ideas and tweaks to the ideas presented here, or case studies of similar successful programs in other cities and countries.

The post Building a Better Density Bonus, Part 3: Leveraging Public Funds to Maximize Private Investment appeared first on .

Building a Better Density Bonus, Part 2: Reducing Thresholds, Increasing Participation 26 May 2015, 6:09 pm

This is Part 2 of a five-part series by Urban One, which outlines recommendations and proposals for improving the California/Los Angeles density bonus program. Part 1 focused on background, while Parts 2 through 5 include specific recommendations to improve the density bonus and affordable housing provision throughout the region.

In Part 1 of this series we discussed some of the background of the density bonus program, how it works, and how it’s fallen short in recent years. One of the key observations identified in the LA Business Council Institute’s recent LA River Report is that only approximately 5 percent of the multifamily units built between 2008 and 2013 were affordable units constructed through the density bonus program—roughly half of what we would expect with full participation. This shortfall costs the city hundreds of affordable units each year, and even more market-rate units, which also play a role in moderating rent increases by absorbing some of the tremendous demand for homes in the Los Angeles market.

Here in Part 2 of the series we begin with our specific proposals/recommendations for improving the density bonus program and increasing the supply of affordable housing in the region. So let’s get started!

Proposal: Reduce thresholds to improve program participation.

The idea behind this proposal is that it’s better to have 50 percent of something than 100 percent of nothing, and, on many density bonus-eligible projects, we’re getting no affordable housing whatsoever. By our estimate only about half of the density bonus units that could be built are actually getting built, for a variety of reasons, and this is significantly reducing the supply of both affordable and market-rate units. Raising participation rates to 100 percent (or as close to it as reasonably possible) should be a priority, and that goal is worth pursuing even if it means reducing the share of affordable units at each individual project.

To put this idea in more concrete terms, imagine two alternative scenarios in which 100 new multifamily buildings are constructed in a year, each with 100 units (base, before the density bonus): In one scenario, 50 of those projects take full advantage of the existing density bonus program and set aside 20 percent of their units as affordable to low income households—those earning 50-80 percent of Area Median Income. This 50 percent participation rate seems to be roughly where we stand today in Los Angeles. In this scenario we end up with 1,000 affordable units and 10,750 market-rate units. (50 buildings with 20 Low Income units and 115 market-rate units, plus 50 buildings with 100 market-rate units.)

In an alternative scenario, the rules are changed such that a 35-percent increase in density is allowed when the developer makes just 15 percent of units affordable to low income households, instead of 20 percent. Here, if 70 percent of developers utilize the program we end up with 1,050 units of affordable housing and 11,400 market-rate units; at 90 percent participation, both numbers increase even further, to 1,350 and 11,800, respectively. By lowering the threshold, there is actually potential to increase the supply of both market-rate and affordable, income-restricted units. Whether such a change would increase participation rates to these levels, or even beyond 90 percent, is open for debate. It’s a debate we should have.

Despite the potential for this to be a win-win scenario for both the city and developers, some might be concerned that this could result in a giveaway to developers. After all, some builders are already taking full advantage of the density bonus and setting aside 20 percent of their units for Low Income residents or 11 percent for Very Low Income residents. For those developers, reducing the threshold does nothing but pad their profits while reducing the total amount of on-site affordable housing. We would caution readers to put the needs of our low-income residents (more affordable housing) above whatever personal anti-developer sentiment they may hold—especially when there is no additional public expenditure—but we respect the fiscally conservative approach and think that the updated density bonus program could be structured to minimize these giveaways.

One way to limit handouts would be to make the reduced threshold program a separate, alternative density bonus, rather than a replacement for the current law. Developers could choose to build up to 20 percent Low Income units under the current program structure, as some do now, or they could take advantage of the reduced threshold—with strings attached. Developers that participated in the reduced threshold program would be subject to a clawback mechanism that shared with the city some of the profit earned beyond a certain level. The clawback amount would be limited, of course, to roughly the value of the reduction in affordable units in the project, so as not to discourage developer participation. To illustrate this idea: If a developer opts to provide 15 affordable units under the reduced threshold program (instead of 20 under the current program) they would be required to share with the city a portion of their profits beyond a 15 percent rate of return, up to $300,000 (for example) for each of the 5 affordable units they didn’t build. If the developer makes a lot of money, the city gets paid back and can fund more affordable housing elsewhere; if the developer loses money, or earns a poor return, the city gets no money but it does get the 15 affordable units. Either way, the city gets a significant amount of affordable housing that may not have otherwise been built.

As we hope to have made clear, tinkering with thresholds and adding a clawback mechanism to the density bonus could help us increase program participation and create more housing for residents at all income levels, making the most of private investment and capturing public value wherever possible. This is just the first of many ideas we have for the density bonus and other policies related to development in Los Angeles, and we look forward to sharing more in the coming days. Stay tuned for Parts 3 through 5!

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5

Note: It is not our intent that the ideas/recommendations included in this series be interpreted as ideal solutions to our city and state’s affordable housing problems. Rather, in the spirit of the LABC Institute’s recent report, we hope to foster engagement and debate about this important subject, and to begin the process of a transition toward more effective and efficient programs that better serve the needs of all LA residents—especially those with limited incomes who suffer the most from a lack of affordable housing. There are undoubtedly a variety of legal and procedural barriers to many of these ideas; some of those are in place for good reason, others may not be and should be reconsidered. Also please note that the ideas in this series are presented on behalf of Urban One and do not necessarily reflect to ideas, recommendations, or values of any other individual or organization.

We invite readers to share their comments and their own ideas for how we might improve the provision of affordable and market-rate homes, implementation ideas and tweaks to the ideas presented here, or case studies of similar successful programs in other cities and countries.

The post Building a Better Density Bonus, Part 2: Reducing Thresholds, Increasing Participation appeared first on .

Building a Better Density Bonus, Part 1: How the Law Works 26 May 2015, 11:09 am

This is Part 1 of a five-part series by Urban One, which outlines recommendations and proposals for improving the California/Los Angeles density bonus program. Part 1 focuses on background, while Parts 2 through 5 include specific recommendations to improve the density bonus and affordable housing provision throughout the region.

A while back we promised to explore in greater detail some of the topics addressed in “LA’s Next Frontier,” the LA Business Council Institute’s report that we helped UCLA’s Paul Habibi to research and write. An important part of that report was the “developer’s toolkit,” which included a variety of programmatic and procedural changes that could help address the city’s housing shortage and economic development needs. In this post and several that follow we’re going to focus specifically on the density bonus, a program that increases the supply of affordable housing by hundreds of units each year, but, as the LABC Institute report makes clear, is falling short of its true potential. Our plan for this series is to examine how the density bonus is being implemented locally and how it might be improved to get more affordable and market-rate housing built throughout the city.

But first, since the density bonus program can be challenging to understand without a bit of context, we’re going to start out this series with some general background. If you’re already familiar with how the density bonus program works, feel free to skip to Part 2.

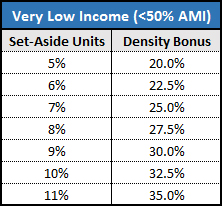

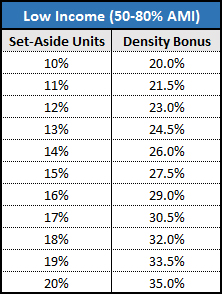

For the uninitiated, the density bonus is a state-mandated program that allows developers to build more market-rate units if they set aside a portion of their building for lower-income residents. The maximum bonus is 35 percent, so on a plot of land zoned for up to 100 residential units, a developer could build up to 135 units if they took advantage of the density bonus. To get the full 35 percent density bonus the developer would need to set aside 11 percent of the units for very-low income residents (up to 50 percent of Area Median Income, or around $33,000 for a four-person household) or 20 percent for low income residents (50 to 80 percent AMI), for a duration of at least 55 years. Additional benefits (“incentives”) can also be conveyed to developers who take part in the density bonus program, such as reductions of minimum parking requirements and leniency on building setbacks and height limits; the 35-percent density bonus can also be achieved with a somewhat smaller share of affordable units if the building is located near a major transit corridor or employment center.

Using the plot of land zoned for 100 multifamily units as an example, a developer who dedicated 11 percent of their units to very low income residents would build 11 affordable units—the 11 percent modifier applies to the pre-bonus maximum density—and in return would be granted the right to build 24 additional market-rate units at the site, for a 35 percent total density bonus. Since affordable units for very low income families can only rent for around $700-1,000 per month, depending on household size, most of the rent in affordable units is spent on maintenance and operations, and very little if any is left over to pay off the cost of construction. This is exacerbated by the ongoing costs associated with compliance, which require the owner to verify that renters in affordable units fall below a specified income threshold. As a result, the cost of building these affordable units is almost wholly subsidized by the profits earned on the additional market-rate units.

According to the LA River Report released last month, of the approximately 30,000 multifamily units constructed in Los Angeles from 2008 to 2013, slightly fewer than 1,500 were affordable density bonus units—about 5 percent. Given that the program requires 11 to 20 percent of units be affordable to receive the full 35-percent density bonus, it’s clear that a large number of developers aren’t taking full advantage of the program, and are either sticking with exclusively market-rate construction or building to less than the full 35-percent bonus. Ultimately this means fewer affordable and market-rate units, which is bad for affordability at all income levels, as more people move to LA and compete for a limited number of homes.

Why aren’t developers taking advantage of the density bonus? There are a few possible reasons. Local anti-growth politics may play a role, where in many neighborhoods the trend is to make projects smaller than is legally permissible, not larger. Another factor may be uncertainty about the density bonus process itself, and compliance costs associated with managing affordable housing. The most likely reason, though, is that the financials simply don’t work out: The additional cost of the affordable units exceeds the profit earned on the extra market-rate units, so the developer can earn a better return without the density bonus, especially when they account for the additional time/money/headache associated with the program’s approval process.

Inclusionary zoning is no longer legal in Los Angeles, so when it’s more profitable for developers to forego the density bonus and build market-rate units only, that’s what they’ll do—market realities generally preclude any other outcome in lieu of public or philanthropic organizations stepping in to fill the gap. What we as a city need to do, and what the numbers show that we’re currently failing to do, is find a way to fill that gap without relying on the charity of developers or outside organizations. This doesn’t mean giving away windfall profits, but it does mean making participation in the density bonus program at least marginally more profitable than non-participation.

This is especially important as we look to use city and county dollars efficiently in an era of scarce resources and many competing priorities. In 2009, the statewide average cost of producing affordable housing rose to $334,000 per unit; in the overheated Los Angeles housing market, that number was probably even higher. Each affordable unit constructed through the density bonus is one less unit that must be built with public funds, and there is an implicit economic cost each time a developer chooses not to participate in the program. For example, if the 100-unit builder from above loses $50,000 of profit on each of the 11 Very Low Income units (relative to the profit they would earn building exclusively market-rate, without the density bonus), they won’t build those affordable units. This saves the developer $550,000, but if each unit has a value of $300,000 when built, the city has given up $2.75 million in free affordable housing (11 x $250,000) by failing to fill that gap. Now, the city must directly subsidize its own affordable housing at a cost of $300,000 or more per unit, or rely on leveraging very limited state and federal dollars. We can’t afford to leave private money on the table.

The question that springs from all of this discussion, then, is “What can we do to restructure density bonus incentives and better achieve our affordable housing goals?” We at Urban One don’t claim to have all the answers, but we’d like to propose a few ideas that we hope can spur a discussion and, eventually, help us to create a greater supply of both market-rate and affordable housing throughout the city.

Our series continues with Part 2, where we explore the idea of reducing thresholds for participation in the density bonus program to increase affordable and market-rate housing production. Parts 3 through 5 will consider additional changes to achieve the same, all while minimizing public investment and leveraging private dollars to the greatest extent possible.

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5

The post Building a Better Density Bonus, Part 1: How the Law Works appeared first on .

ULI YLG Art of Development Series: Design and Construction 22 May 2015, 9:44 am

Urban One will be sponsoring Urban Land Institute LA’s (ULI/LA) Young Leader Group (YLG) event coming up on June 2, 2015 titled “Art of Development Series: Design and Construction.”

This is the last segment in the three-part Art of Development Series. ULI has a distinguished panel of Design and Construction experts to “shed light on how to take a developer’s overall vision and turn it into reality.” The panel will discuss past and current projects as case studies, explaining how they have brought a vision into a reality, with an emphasis on design and construction. The panel will be a mix of Architects and General Contractors.

This will be a great event for someone looking to get a basic understanding of the design and construction process or even for the seasoned development professional just looking to freshen up on their skills and do a little networking.

We hope to see you there!

Urban Land Institute Los Angeles YLG Art of Development Series: Design and Construction sponsored by Urban One

Urban Land Institute Los Angeles YLG Art of Development Series: Design and Construction sponsored by Urban One

Date: June 2, 2015

Time: 7:00 pm – 9:00 pm

Venue: Southern California School of Architecture – Keck Auditorium

Address: 960 East 3rd Street,Los Angeles,CA 90013

[button link=”http://la.uli.org/event/ylg-art-development-series-design-construction/” newwindow=”yes”] Click here to register for event[/button]

The post ULI YLG Art of Development Series: Design and Construction appeared first on .

New Report Explores LA River’s Potential For Sustainable Development and Social Equity 27 Apr 2015, 9:30 pm

Urban One was privileged to work with Paul Habibi of Grayslake Advisors and the LA Business Council Institute on a new report, released this past Friday, exploring the sustainable economic development potential of the LA River and its surrounding neighborhoods. The report, “LA’s Next Frontier: Capturing Opportunities For New Housing, Economic Growth, and Sustainable Development in LA River Communities,” details the many economic, social, and environmental benefits that can be achieved for the city and its river-adjacent communities through investment in ecosystem restoration and sustainable infrastructure development, including affordable housing.

One of the most surprising results of this study was the level of environmental inequity found within our region. According to data from the state’s CalEnviroScreen report, which identifies pollution burden and negative socioeconomic indicators in California communities, nearly 40 percent of neighborhoods within one mile of the LA River fall between the index’s 90th and 100th percentile—the most-burdened ten percent of census tracts in the state. This is double the rate of highly-polluted and demographically vulnerable census tracts in LA County, and nearly four times the rate found in the state as a whole. Restoring the LA River ecosystem and connecting its surrounding neighborhoods with greenway paths, parks, and other sustainable connections and destinations will go a long way toward righting this historic wrong.

Revitalization will also bring economic benefits to local residents, many of whom have suffered from the departure of manufacturing and other middle class jobs out of the city. Renewed interest in the river has brought developers and other investors to its banks, and with them come opportunities for providing jobs and services that river-adjacent neighborhoods now lack. The city and region as a whole can benefit from this new investment, as the state, county, and City of Los Angeles unemployment rates all remain elevated above the U.S. average.

The report acknowledges that increasing development has the potential to impact housing prices and lead to displacement of existing residents. Mr. Habibi and the LA Business Council Institute therefore identify provision of affordable and workforce housing—in addition to new market rate units—as one of the primary long-term goals for investment in these communities. River neighborhoods can play a major role in helping the city meet Mayor Garcetti’s goal of building 100,000 units by 2021, with room to add 8,000 units per year in river-adjacent neighborhoods in the city, all without dramatically increasing density. With the appropriate planning and financing tools in place, a substantial number of new units could be made affordable to lower-income and moderate-income residents.

To pay for ecosystem restoration, sustainable development infrastructure, affordable housing, and other local priorities, the report identifies Enhanced Infrastructure Funding Districts (EIFDs) and stormwater mitigation credits as two particularly promising funding options. EIFDs are able to capture property tax increment revenues and bond against them, similar to the state’s former redevelopment agencies (though with more limitations), and can also raise other funds via fees and assessment revenues. An analysis of the tax increment potential of properties within one mile of the river finds that a conservative increase in property values of 2 percent per year would raise approximately $5.6 billion over 45 years; an “enhanced” growth rate of 3 percent per year would increase revenues to $10 billion over the same time period.

The stormwater mitigation credits proposed in the report would seek to take advantage of the market-making potential of cap-and-trade, similar to the state’s cap-and-trade program for carbon emissions. The following example from the report helps make the program’s benefits clear:

[I]magine the owner of a flat parcel of land with high soil porosity. That owner might choose to invest extra funds into stormwater recapture on her site due to the high efficiency of water retention per dollar invested. Having exceeded the average stormwater retention requirement for a parcel of her size, she could then sell a portion of her credits to the owner of a hillside parcel for whom investing in retention infrastructure would be costly and relatively ineffective.

Under such a system both parties profit: The owner of the flat parcel is able to earn a profit on the sale of her stormwater retention credits (she earns more from sale of the credits than it cost to build the additional retention infrastructure), and the owner of the hillside parcel is able to purchase the credits at less expense than it would cost to build additional retention infrastructure on his unwieldy site. Communities and the local government also benefit: They achieve at least the same level of total water recapture as if each site had managed its stormwater recapture independently, and they reduce the risk that onerous environmental regulations will prohibit otherwise productive redevelopment that increases the supply of housing, creates jobs, and contributes to a stronger tax base.

This latter recommendation comes at an important time, with the entire state in drought and Governor Brown recently imposing across-the-board cuts on urban water use. As one panel member at the LA Business Council Sustainability Summit noted, opportunities for the use of cap-and-trade programs to improve resource efficiency aren’t limited to stormwater recapture, and could be applied to other efforts such as water conservation for the mutual benefit of property owners and policymakers—we would add, however, that this is dependent on thoughtful, strategic implementation.

The report concludes with a discussion of several important planning tools and policy reforms that could be used to complement the above funding sources, and a recommendation for two “pilot districts” in which these tools could be applied: Studio City-North Hollywood, and Northeast LA, including parts of Atwater Village, Lincoln Heights, and Highland Park. The tools in this “developer’s toolkit” include reforms to the density bonus program, the use of local design guidelines, and by-right development for projects that conform to rules and guidelines laid out by the community; we hope to explore these and other aspects of the report in greater detail in the weeks to come.

Check out the report for yourself, and stay tuned!

The post New Report Explores LA River’s Potential For Sustainable Development and Social Equity appeared first on .

Is your city Manhattanizing? Probably not within the next few hundred years. (CHARTS) 14 Apr 2015, 9:00 am

Every successful city grows and evolves over time, but is your city Manhattanizing?

For those unfamiliar with the term, Manhattanization is best described as the fear among some residents of growing cities that if population growth continues unabated, there will be no room left for anything but townhomes, apartments, and pencil-thin skyscrapers. The streets will be overrun with traffic and tourists, Wall Street will move in, balls will drop on live television, chaos will ensue.

For those of us who have been to (and enjoyed) New York, this may not sound so terrifying. But for many people, it seems to be a real concern: A cursory Google search reveals writing on the subject all across North America, from Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, and Las Vegas, all the way over to Boston and Toronto. Curbed Miami has its own “Manhattanization of Miami” search tag. Even Brooklyn, right across the East River, has its doomsayers.

The question is, what would Manhattanization actually look like for these and other large U.S. cities? How much would they need to grow to reach Manhattan’s current population density of approximately 70,000 people per square mile? And, at current growth rates, how long would it take them to get there?

The answers can be found below in two graphs, compiled from U.S. Census and American Community Survey data. The first compares the current population of many cities (note: cities, not metros) to what their populations would be at 70,000 people per square mile—not surprisingly, most cities would be much, much larger. Even the closest to complete Manhattanization, New York itself, would need to almost triple in population. San Francisco, the next closest, would have to more than quadruple its population. In the graph, the black line for each city represents its current population, the blue bar is population at 70,000 people per square mile, and the number to the right of each bar is the population multiplier—how many times larger the city population would be if it grew to the density of Manhattan.

What this graph illustrates pretty clearly is that every city in the U.S. has a long way to go before even approaching true Manhattanization. While select neighborhoods may be quite close—my neighborhood in Koreatown, Los Angeles houses about 40,000 people per square mile, for example—citywide or even large-scale Manhattanization is far out of reach for most cities, even relatively dense places like Boston and Chicago. And while many of us wouldn’t find it appealing to have such densities spread uniformly throughout our cities, most of us can appreciate the value that a variety and diversity of urban typologies brings to our lives. These numbers demonstrate that regardless of where you live, your city has plenty of room for a wide range of neighborhoods, from single-family to skyscrapers and everything in between.

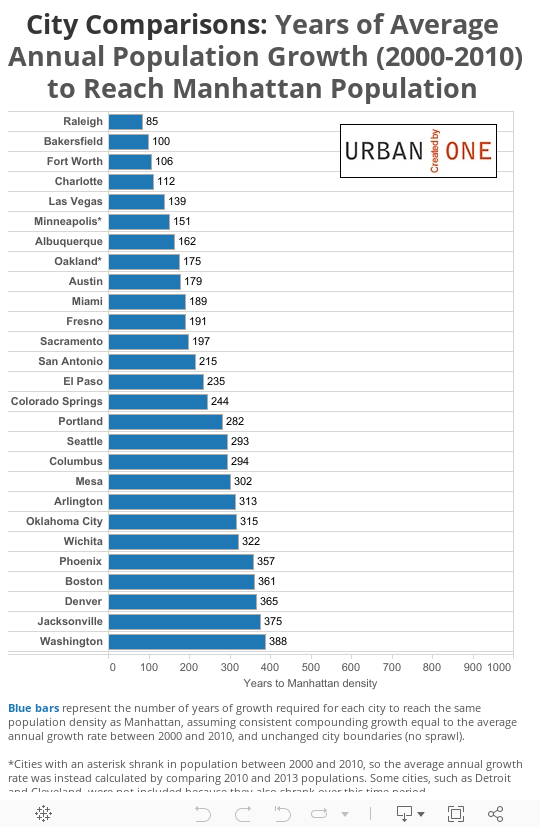

The next graph looks at how quickly cities grew between 2000 and 2010, and uses that information to determine how long it would take to grow to the population density of Manhattan, assuming that the same growth rate continues forever. For the small number of cities that actually lost population over this time period, we looked at growth between the 2010 Census and 2013 one-year American Community Survey. Annual growth rates are compounded in this analysis, so 2% annual growth would more than double the population of a city over a 50-year period.

Based on current growth rates, the cities with the highest population density today would not be the first ones to reach 70,000 people per square mile. This is mainly because larger, denser cities tend to grow more slowly. In reality, places like Raleigh and Bakersfield won’t be achieving Manhattan-esque (or even very high) population densities any sooner than New York or Boston, because as they continue to grow in population their annual growth rates will decline. Select neighborhoods in larger cities grow rapidly—such as Downtown LA, which accounts for 1 percent of Los Angeles’ land area but 20 percent of its growth—but the overall decades-long trend has been for construction and population growth to slow down as new regulations are put in place and urban construction costs increase.

Another caveat is that the above graph doesn’t take into account the physical expansion of cities: While places like San Francisco and Manhattan are physically constrained by geographic features (i.e., they can’t grow into the water), other cities are not so limited. Raleigh, Bakersfield, and Charlotte all increased their populations by at least 35 percent between 2000 and 2010, but they also increased their physical footprint by at least 25 percent, so their density changed relatively little.

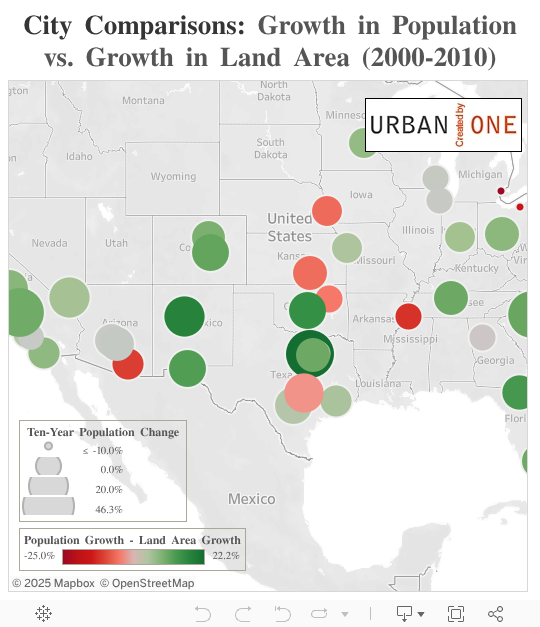

One last map, below, compares population growth to the physical expansion (through annexation, generally) of various U.S. cities. It shows that while many cities grew significantly in population between 2000 and 2010—represented by larger bubbles—some grew by increasing density, while others grew primarily by increasing their land area—darker green means that population growth exceeded physical expansion, red means that expansion was greater than population growth. Examples of all different types appear in the map. Austin shows up as large and red because it added many residents, but it increased its physical size to an even greater degree. Detroit and Cleveland are small and red because they lost population and did not increase their footprint; Memphis is relatively small and red because, while it grew slightly (1.0%), it increased its footprint by much more (13.6%).

Many cities, including Phoenix and Chicago, are grey because their population growth and physical size grew in rough proportion to one another, so that densities were mostly unchanged. These provide some context for the above map, highlighting why looking at just population growth can be misleading. Last, there are cities that increased their population significantly more than they physically expanded, and these show up as darker green.

Overall, current growth rates for most large cities seem to indicate that the threat of Manhattanization is overblown. Despite claims of record growth and a booming development sector in many cities, new unit construction remains far below peak levels for many cities. Rather, growth has been relegated to such a small number of density-friendly communities that it has become far more visible, even as its absolute numbers have declined.

The term “Manhattanization” is also sometimes used to the extreme gentrification characteristic of the borough—the kind that displaces lower-income and middle class residents and gives it the perception of being a playground for the rich, not a place where average, everyday people live. Paradoxically, however, it’s the fear of increased density that led to coastal cities becoming the most expensive housing markets in the country. In response to the anti-growth, anti-“Manhattanization” movement, places like Los Angeles have successfully reduced their population capacity through a combination of new regulations, legislation, and bureaucratic processes that put a hard cap on growth. Those caps haven’t stopped cities from attracting more businesses and residents, but they have ensured that every new resident has to outbid a current resident for the privilege of living here—a recipe for guaranteed gentrification and displacement.

Knowing what we know now—that putting a halt to construction places the burden of growth on our poorest residents, and that every city has plenty of room for additional housing without having to fear Manhattan-style crowding—our focus now should be increasing the supply of housing at all income levels. We should encourage every type of housing: luxury because it will produce revenues necessary to subsidize affordable housing construction, and because it takes the demand pressure off homes in the middle range; moderate-income housing because our cities won’t succeed without teachers, office workers, or students; and low-income housing, because no matter how much we build, market rates will always be out of reach for some, including many of our seniors. If we finally commit to this course, and after a few hundred years of providing our residents with a better, more affordable quality of life, it turns out that we’ve built ourselves another Manhattan or two, well, that doesn’t sound like such a bad trade.

Note: For those interested in larger versions of these charts and map, they can be found at the following links. Feel free to share with attribution to Urban One.

The post Is your city Manhattanizing? Probably not within the next few hundred years. (CHARTS) appeared first on .

Do Hotel Subsidies Make Sense for Los Angeles? 15 Dec 2014, 6:17 pm

There’s more value to building hotels than just boosting tourism at the downtown convention center: The city is spending $39.2 million in foregone tax revenue to encourage Metropolis to build a hotel, but that hotel will generate $110 million more in city revenues than a similar residential tower built at the same location.

Over the past decade, developers in Downtown LA have received some big tax breaks to encourage hotel construction near the city’s convention center; with the city struggling to afford many basic services like street and sidewalk repairs, some have questioned whether this is the most responsible use of limited public funds.

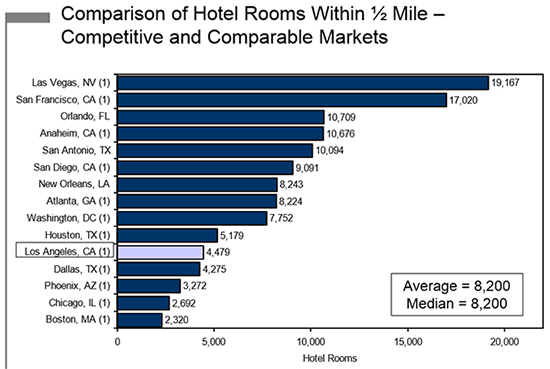

For proponents, the idea behind these subsidies is that in lieu of city assistance, developers would just build something else — something cheaper or less risky, like apartments — and that the city would lose out on hotel space needed to support the convention center and LA Live entertainment district. The need for additional hotel rooms has been the main argument in favor of these subsidies, and it’s a legitimate problem: According to a study by Conventions Sports & Leisure, Los Angeles has just 4,500 hotel rooms within a half-mile of its convention center, compared to 9,000 in San Diego, almost 11,000 in Anaheim, 17,000 in San Francisco, and over 19,000 in Las Vegas. Without sufficient hotel space in close proximity to the downtown convention center, LA can’t really compete for the biggest, most popular conventions.

The cost to the city for incentivizing these downtown hotels has been a big focus among outlets like Curbed and the LA Times, but what’s received less attention is the long-term revenue implications for the city. The Greenland Group’s Metropolis development — a billion dollar residential and hotel project just north of LA Live — was the most recent recipient of a tax rebate valued at $39.2 million over 25 years, and it’s a great case study for looking at the impact of these subsidies on the overall city budget. Greenland has one of two choices for their first phase of development, and they can reasonably go either way: build a residential tower and a hotel tower, or just build two residential towers.

According to an analysis by Keyser Marston Associates (KMA), Greenland’s 350-room hotel tower is projected to cost $13.5 million more than a second residential tower, so that’s the gap the city needs to fill to incentivize them to build a hotel instead of more housing. The amount of subsidy the city can provide is currently limited to either 50 percent of all new tax revenues (property tax, sales tax, hotel tax, etc.), or 100 percent of hotel taxes alone, whichever is less. There has been debate in the past year about revising those amounts in certain parts of the city to 25 percent and 40 percent, respectively, but there are concerns that this will make it even harder to attract the large hotel developments (e.g., 600, 800, 1000 rooms) that downtown is already struggling to attract. In this case the project’s need was fairly limited, and the city committed to providing just 25 percent of net new revenues, at a total value of $13.1 million — just shy of the feasibility gap between hotel and residential. Presumably, the Metropolis developers are willing to eat the $400,000 difference to earn some goodwill with the city.

And for those wondering how a $13.1 million funding gap becomes $39.2MM in subsidies: For the same reason that I’d gladly pay you Tuesday for a hamburger today, $13.1MM up front has the same value as $39.2MM paid out over 25 years. (For the finance nerds, $13.1 million is the 25-year net present value.) It’s also important to note that the city’s assistance only comes out of new revenues generated by the project, so even if the development was a total failure the city could never lose money.

So, in the long term, $39.2 million is what it’s costing the city. What do we get in return? The key to that question is understanding that different types of projects create different types of revenues. Residential and hotel projects both generate property tax revenues for the city, but hotels generate additional revenues in the form of sales, gross receipts, and parking taxes (among others), and, most importantly, the all-mighty hotel tax. The hotel tax — also known as the transient occupancy tax or “TOT” — is hugely important for cities: it’s 14 percent of room revenues and it all goes to the city of LA. Compare that to the sales tax, of which only 1 percent actually goes to the city. Residential projects tend to be cheaper to build and produce more consistent revenues so they appeal to developers, but they don’t generate any of these additional tax revenues for the city.

Keyser Marston looked at the projected revenues if Greenland builds a 350-room hotel and a 308-unit condominium, and they estimated that the two towers would generate a total of $161 million in city revenues over 25 years. Of that total, $135 million is generated by the hotel, and $25 million by the condos. And of the $135MM generated by the hotel, $104MM comes from hotel taxes alone. Again, it’s all about the hotel tax. Here’s how the numbers break down according to KMA:

If the Greenland Group decided to build two residential towers at the Metropolis site instead of a hotel and a condo tower, the city would earn about $110 million less over the next 25 years. Even after accounting for the $39.2MM tax rebate, we’d still be about $70 million poorer. Here’s another table that compares the two scenarios:

Based on this analysis, it seems clear that there’s good reason to incentivize builders that are on the fence about building hotels. Even if you’re indifferent to the fate of Los Angeles as a major convention center and tourism destination, this is a simple economic reason to support building hotels rather than more upper-scale housing in the downtown entertainment district. In this case alone, the city can expect about $70 million additional dollars of revenue over the next 25 years compared to what we’d get from another condo tower.

At this point the astute reader will note that if the developer intended to build a hotel anyway, we just gave away $39 million for nothing. It’s a fair critique, since the way that development plans are put together involves a lot of assumptions and a lot of potential flexibility. We just can’t know for certain which of these projects, if any, might have been built with less assistance, or even none at all. But this is also the reason firms like KMA exist: to determine the extent of a developer’s need on behalf of the city, from an objective, critical perspective. Their job is to determine the “but for” value — the amount of assistance needed, but for which the hotel would not be built. It’s a tough job with a million moving targets, so really knowing that we’ve landed on the right amount is essentially impossible. What we do know, at least, is that hotels are a cash cow for the city; as long as we need the additional rooms, it might be worth sharing the bounty to ensure they continue getting built.

The post Do Hotel Subsidies Make Sense for Los Angeles? appeared first on .