Add your feed to SetSticker.com! Promote your sites and attract more customers. It costs only 100 EUROS per YEAR.

Pleasant surprises on every page! Discover new articles, displayed randomly throughout the site. Interesting content, always a click away

The First Special Service Force During The Second World War 18 May 2023, 12:47 am

From America and Canada to Alaska, Italy and France: The First Special Service Force During the Second World War

When the United States was dragged unceremoniously into the Second World War following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the Philippines in December 1941, it was way behind in terms of its special operatives’ capabilities. Already by that time Britain had been sending crack units of commandos to coastal sites in Norway, France and other countries to target Nazi installations since late 1940. Therefore Uncle Sam had a lot of catching up to do. Much of this, in the early stages of US involvement in the war, would be undertaken through the First Special Service Force.

The origins of the First Special Service Force can be traced to the visit of General George Marshall, Chief of Staff of the US Army, to Britain in the early spring of 1942, just over two months after America’s entry into the war. During this sojourn Marshall was introduced to an eccentric British scientist by the name of Geoffrey Pike who had come up with a plan to try to divert hundreds of thousands of German troops from the main arenas of the war to sites in peripheral theatres in Norway and other locales by launching commando raids. It was Pike’s aim that these commando units would use specialized vehicles to launch raids in the winter of 1942 against, for instance, targets in Norway and Romania such as oil refineries and then use these operations to force Berlin to divert massive numbers of troops away from France and Eastern Europe to protect its supply of vital resources. Although the details Pike provided were limited Marshall was intrigued by the plan and returned to Washington with a desire to convince the heads of staff to form a new US commando unit.

In June 1942 the first elements of the First Special Service Force were formed out of American and Canadian units under the command of Colonel Robert Frederick. Training began at Fort William Henry Harrison near Helena in the state of Montana. Eventually it would consist of upwards of 1,400 troops, of which approximately 60% were Americans and the other 40% were largely Canadians. Although these were to be crack units, their training was rudimentary in many respects. For instance, troops were only given six days of airborne training, meaning that if parachuted into a theatre of operations they would have little experience of what was occurring.

In the end, despite Pike’s earlier plans for missions in Norway and Romania, the First Special Service Force was not brought into operation until the summer of 1943 when they were transferred to Alaska. The Japanese had occupied several of the Aleutian Islands here between the north-western point of America and the north-eastern extremity of Asia in 1942. Two islands had remained in Japanese hands and now the First Special Service Forces were called on to aid in the recapture of the island of Kiska. Nevertheless, this proved a quick, largely abortive campaign, as the Japanese simply abandoned the region once the Americans and their allies made their presence known. As such, even here, a year and a half after the unit had been formed, it was not brought into significant action.

Eventually, in October 1943 the First Special was finally made proper use of. In the summer of that year, having completed the conquest of the Axis powers’ territories in North Africa, the Western Allies had launched a naval invasion of Sicily in southern Italy. The fascist government in Rome had then overthrown its leader, Benito Mussolini, but a German counter-measure followed and Italy became a major front in the wider war. It was here that the First Special was first dispatched to capture some elevated strategic sites on the Monte La Difensa and Monte La Rementanea, which were blocking the Allied advanced into the Liri River Valley in south-central Italy. Here, after Frederick had reconnoitered the 3,000 foot high La Difensa peak, the First Special conducted a night-time raid in early December to capture an elevated position. This was carried out effectively and the route-way was opened up by the First Special towards Cassino on the way from southern Italy to the province of Lazio near Rome itself.

While this commando operation was significant in the winter of 1943, it was followed by weeks of inaction. No special operatives’ missions were decided upon in Italy and the First Special remained without any significant engagement other than some standard unit missions against the Axis front lines south of Rome that winter. Eventually, though, Frederick and his men were redeployed to the Anzio region where a fierce battle was being fought between German and Italian troops and the Western Allies. On this battle, which lasted between January and early June 1944, was the fight for Rome decided. It was here that Frederick’s 1,300 or so troops in the First Special Service Force defended a huge 52 kilometer long perimeter. During this period the First Special engaged in night raids in an effort to locate targets for artillery bombardment and air-bombings. As such, the First Special played a considerable role in the entry by the Western Allies into Rome on the 4th of June 1943. There they secured some of the first bridgeheads over the River Tiber in central Rome.

After the Italian campaign the First Special Service Force was sent to the south of France with the goal of seizing major sites there as a southern front was opened not far from Marseilles weeks after the Allies had opened a western front in Europe in the north of France. By this time the unit was under the command of Colonel Edwin A. Walker, who was no stranger to using boats made of rubber to sail to and land on the beaches of Ile de Port Cros and Ile du Levant, islands on the southern coast of France. The Axis garrison there quickly surrendered within 48 hours of the first arrival of the First Special on the shores of these archipelagos.

Within two days the defenders on these small islands had surrendered, a somewhat unsurprising development given their hopeless circumstances. On retreating, though, from this point onwards the unit was badly impacted on and suffered several losses. As a consequence, by early September 1944 the First Special Service Force was massively depleted from the numbers it had when it was created two years earlier. As such, the unit was sent off to serve in a standard capacity along the Franco-Italian border. It served there for three months before being ordered to stand down in the early winter of 1944. It was at this juncture, in December 1944, that the unit was informed that it was to effectively be disbanded and its members would be transferred to other units. Thus ended the short, but significant, life of the First Special Service Force.

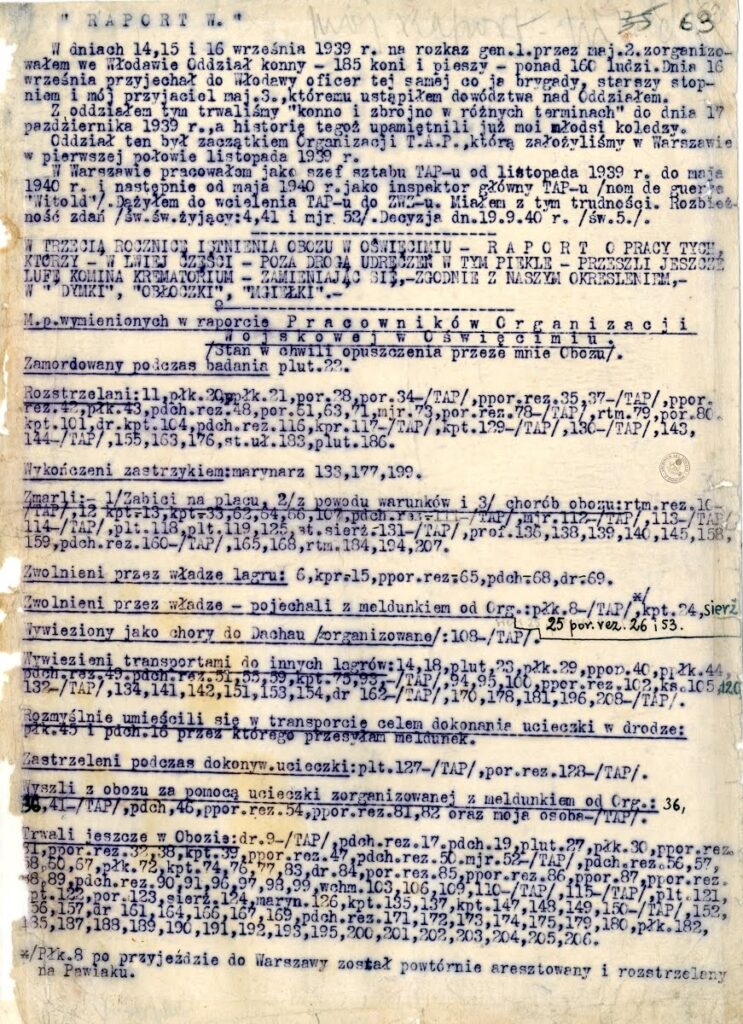

Front to rear: Lt. T.C. Grodon of Welland, Ont., S/Sgt. A.C. Mack of Pittsburgh, Kansas; Sgt. W.E. Watson of Hamilton, Ont. [of Special Service Force.] 3397562

The post The First Special Service Force During The Second World War appeared first on WW2 Helmets™.

The “Eagle’s Nest”: The Berghof, Hitler and Nazi Germany 29 Mar 2023, 1:35 am

One of the classic films based during the Second World War is Where Eagles Dare. Released in 1968 and starring Richard Burton and Clint Eastwood, the film tells the story of British and American special operatives disguised as German soldiers sneaking into a Nazi stronghold high up in the Bavarian Alps. Their goal is to rescue an American agent who has key plans relating to the planned Allied invasion of France. The story is entirely fictional and no such mission was ever undertaken, but the set-up of a Nazi stronghold high up in the mountains is closer to reality than one might think, for the Nazi leadership did indeed have such an Alpine retreat. Indeed the Berghof was more central to the politics of the Third Reich than one might think.

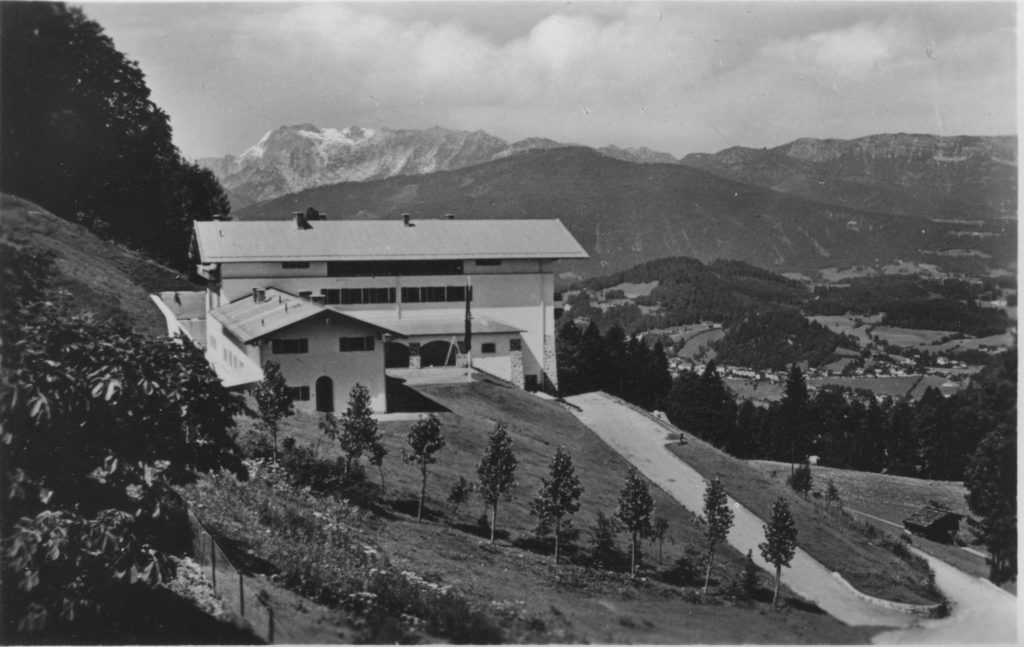

Hitler had always had an affinity for the Alpine region. It was here on the Austrian side of the German-Austrian border that he was born at Braunau am Inn in 1889. The Nazi Party was effectively a Bavarian political party before it became a German one and the Alps straddle the southern parts of Bavaria. Indeed, after he became Nazi leader and once he was released from Landsberg Prison late in 1924 Hitler began vacationing regularly at Berchtesgaden, the Alpine region in the extreme south of Germany. He subsequently purchased a house here, high up in the mountains with money from the sales of his rabidly Anti-Semitic, paranoid conspiracy theory-laden political manifesto, Mein Kampf. Then, following his rise to power as Chancellor of Germany in 1933, he employed the architect, Alois Delgano, to renovate and expand the chalet into a grand mansion. This would subsequently become known as the Berghof, meaning ‘Mountain Court’, but to most others it was known as the ‘Eagle’s Nest’.

When it was complete the Berghof towered 3,000 foot above ground looking out over Bavaria and Austria. Extensive rooms were laid out for Hitler and his partner Eva Braun and visiting guests. A great hall was expensively decorated with eighteenth-century furniture to entertain guests, while Renaissance paintings and Baroque ornaments were purchased for the entranceway and other rooms. The most impressive section was the large terrace with its panoramic view of the Alps and Bavaria. And the Berghof was not the only building constructed here. Local landholders were forced to sell their properties so that other senior Nazis could build their own mansions nearby. An airstrip was even constructed so that small planes could fly the Nazi leadership in from Berlin, while an elevator was built to convey individuals from the Eagle’s Nest down the mountain to the town of Berchestgaden, the latter of which effectively became a service town for the Nazi settlements towering above it.

Hitler was fond of keeping his quarters outside of Berlin. For instance, during the Second World War he based himself in the Wolf’s Lair, a massive bunker in western Poland, rather than in the German capital. Other than the Wolf’s Lair, the Berghof was his favored haunt. As such, it became the site for many high level diplomatic meetings over the years. When the Austrian quasi-dictator, Kurt von Schuschnigg, was attempting to prevent the union of Germany and Austria early in 1938 he met with Hitler at the Berghof. Seven months later it was the turn of the British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, as he sought to prevent German annexation of the Sudetenland. Other guests to the Berghof included the Aga Khan, David Lloyd George and Benito Mussolini. Hitler also convened a meeting of his generals here in the late summer of 1940 at which he first instructed them to begin drawing up strategic plans for the invasion of Russia.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given how much time he spent here, the Berghof was also associated with several efforts to assassinate Hitler. The German army captain Eberhard von Breitenbuch arrived there with a concealed gun on the 11th of March 1944 with the intention of killing the Fuhrer, but he could not obtain an audience with him. Claus von Stauffenberg originally intended on planting a bomb here to assassinate Hitler in June 1944, before eventually doing so at the Wolf’s Lair on the 20th of July. The British also planned to assassinate Hitler here in Operation Foxley, a plan whereby snipers would parachute into Austria and then traverse the mountains to the Berghof, killing Hitler from afar during his twenty minute daily exercise routine. However, before this was decided upon Hitler stopped visiting the Berghof and increasingly ensconced himself in either the Wolf’s Lair or the Chancellery bunker in Berlin.

In the spring of 1945, as the Russians edged towards westwards towards Berlin, many of Hitler’s confidantes urged him to abandon the German capital and head for the Alps, where a last stand could be made in the mountains around the Berghof. Some even hoped that if they held off for long enough the Western Allies and the Soviets would end up falling out with each other. But Hitler was adamant he would stay in Berlin and it was there he killed himself on the 30th of April 1945. Most of the other Nazi leaders headed north-west to the border with Denmark where there were few Allied troops and where they formed a temporary government. But Goering did go south, armed with a briefcase full of the opiates he had been addicted to for over twenty years. He floated in around the Berchtesgaden area in late April, but eloped over the border to Austria eventually as American troops neared the Berghof.

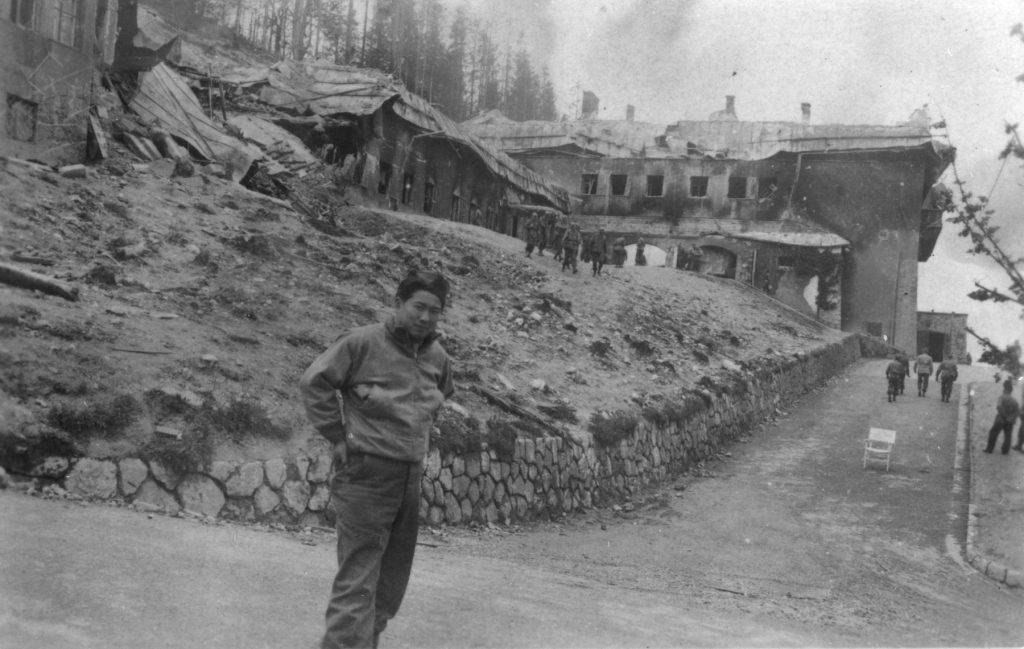

Eventually it was the 7th Infantry Regiment of the US 3rd Infantry Division which arrived to Berchtesgaden first. They got there on the 4th of May, but they didn’t head right up the mountain to the Berghof. It was the French 2nd Armoured Division that did so shortly afterwards. There they made an astonishing discovery, a wine cellar under the Berghof, which was replete with approximately half a million bottles of fine wine, champagne and cognac. Word spread quickly and by the afternoon of the 5th of May Allied divisions were arriving to the Berghof to fill their trucks, tanks and whatever else could be filled with wine bottles. The elevator to the mountain side retreat was broken, so a medical unit was even brought in to stretcher casks of wine up and down the hillside to a car park below. By the time Victory in Europe was announced on the 8th of May 1945 there were many sore heads already in southern Germany.

While the wine cellar was intact, the Berghof itself and some of the surrounding houses and buildings had been badly damaged by Allied bombings in late April 1945 and then the SS had set fire to sections of it before abandoning it in the face of the approaching Allies in early May. Thus, it was already quite damaged by the time the war ended. Nevertheless, a decision was made by the Americans, in whose zone of occupation it was located after the war, that it should be destroyed, along with the houses located there of other Nazi leaders such as Goering and Bormann. This was to avoid the site becoming a neo-Nazi shrine in years to come. Thus, in 1952 by order of the German government the last of the building’s shell was destroyed.

The post The “Eagle’s Nest”: The Berghof, Hitler and Nazi Germany appeared first on WW2 Helmets™.

The WWII Soldier Who Didn’t Surrender Until The 1970’s 7 Jun 2022, 1:16 am

There are few wars that have ended as strangely as the Second World War in the Pacific Theatre. For instance, the Russian Federation and Japan are theoretically still at war with each other, as certain territorial disputes concerning lands along the north-west of the Pacific Ocean were never fully resolved in 1945. More curious still was the fact that many Japanese garrisons and brigades refused to accept that the Empire of Japan had been defeated in the autumn of 1945 and the emperor in Tokyo had signed the official declaration of surrender on the 2nd of September 1945. Some of these soldiers were confined to small bunkers and military strongpoints on isolated islands around the Japanese archipelago or various other islands in the western Pacific. Accordingly some simply did not know for an extremely long time that the war was over and in some instances continued to fight against anyone who approached their positions for months or even years after the war ended. Some of these so-called Japanese holdouts fought on until the late 1940s or even much later, cut off from the world and still determined to fight a war which was over.

Of all of these Japanese holdouts a handful stand out. Teruo Nakamura was the most resilient. An Amis aborigine from Taiwan, Nakamura had been stationed on the island of Morotai in the north of what were the Dutch East Indies at the start of the Second World War, but which subsequently became part of Indonesia. The Allies overran Morotai in September 1944, but Nakamura and several others remained in the woods and refused to surrender. When the war ended a year later they received no word of this and continued to fight on as guerrilla soldiers in the jungle. Eventually, in 1956 Nakamura’s companions gave up the cause and returned to civilization, but Teruo continued his fight alone and continued to reside in a small hut which he constructed on a 20 by 30 meter field in the middle of the Morotai wilds for the next twenty years. It was not until 1974, when the Indonesian government decided to intervene, that Nakamura was brought back to civilization as it were. He was the last Japanese holdout to accept that Japan had lost the war, over 28 years after the war ended.

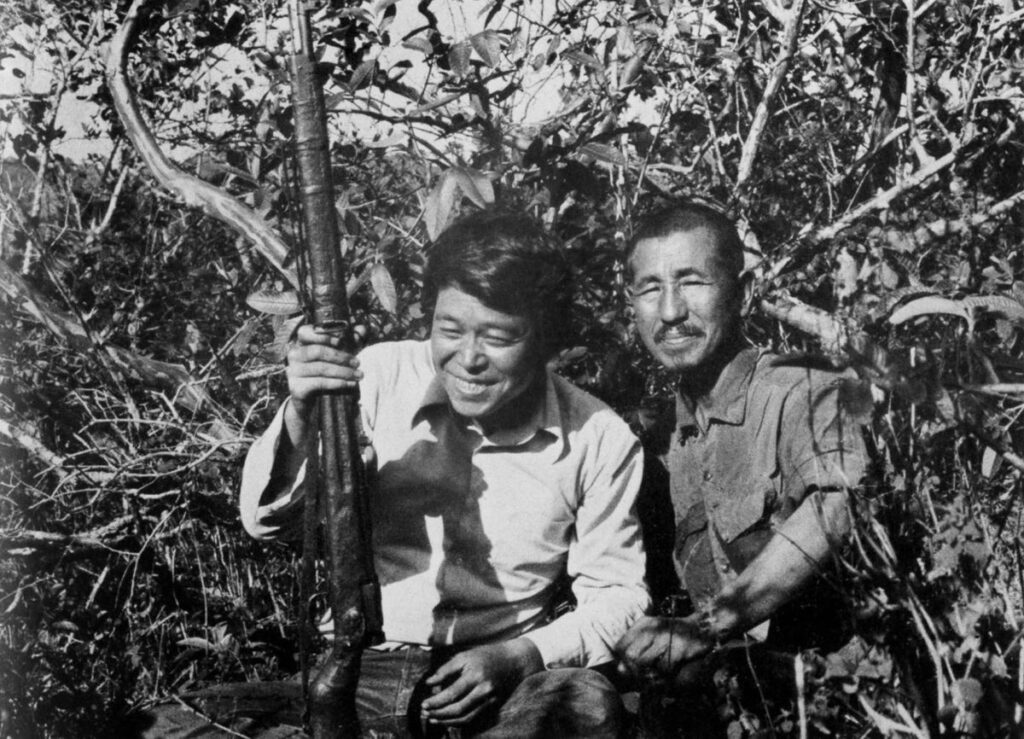

Nakamura’s story is eclipsed by just one other, that of Hiroo Onoda. Onoda was the penultimate Japanese holdout to surrender and only eventually ended his own personal war a few weeks before Nakamura did in 1974. Onoda was a Japanese native from Wakayama prefecture who was born in 1922. During the early years of the war he trained as an intelligence officer and was committed to the ultra-nationalist and quasi-fascist political ideology of the Empire of Japan. On the 26th of December 1944 he was sent to Lubang Island, one of the north-westernmost islands of the Visayas, the Middle Philippines or islands which dot the archipelago between Luzon in the north and Mindanao in the south. Here he was commanded to do everything in his power to stop the Allied re-conquest of the Philippines by destroying the airstrip which was being developed by the Americans there and attacking various other sites as the island was still an active theatre of the war.

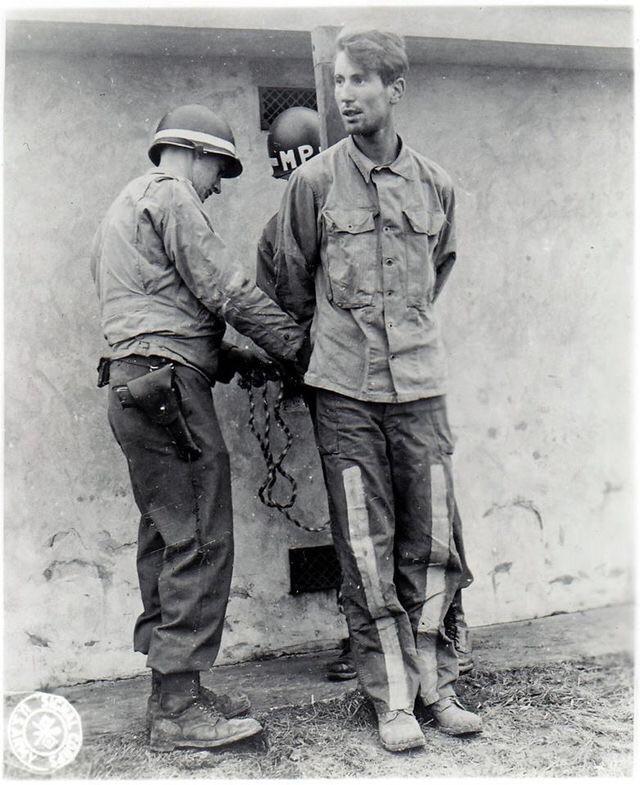

Image: Norio Suzuki via reddit

Onoda and his fellow soldiers were presented with their first opportunity to surrender in February 1945 when the US and their allies took full control over Lubang Island. However, Onoda decided to continue the fight against the Americans and their allies and commenced a campaign of guerrilla attacks on Allied personnel and bases. This continued for months thereafter, even as the war was heading towards an inexorable conclusion in the wider Pacific Theatre. Once atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and then needlessly on Nagasaki the emperor in Tokyo announced Japan’s intention to surrender. But it was not until October 1945 that Onoda and his small group of fellow soldiers first came across a leaflet with a command from General Tomoyuki Yamashita, which had been dropped on Lubang Island, like many other islands across the Western Pacific, alerting them that the war was over and they should now surrender. Onoda, like many other Japanese holdouts, believed this was a ploy by the Americans and so he refused to countenance surrendering.

As the months and then the years passed Onoda, like Nakamura on Morotai island to the south-west, was gradually abandoned by his fellow holdouts, many of whom simply walked out of their camp and surrendered to the Filipino authorities. However, a small coterie of soldiers continued to fight with him. They engaged in attacks on military and civilian targets, often ending up in shootouts with local fishermen whom they allegedly believed to be Allied soldiers. Despite repeated leaflet drops, which in the 1950s included signed letters from their own family members, they continued to defy the request to surrender. But as the years passed, their numbers declined, until in 1972 it was just Nakamura who was left. His last companion, Private First Class Kinshichi Kozuka, was killed that October as they were attacking a rice depot as part of their guerrilla activities.

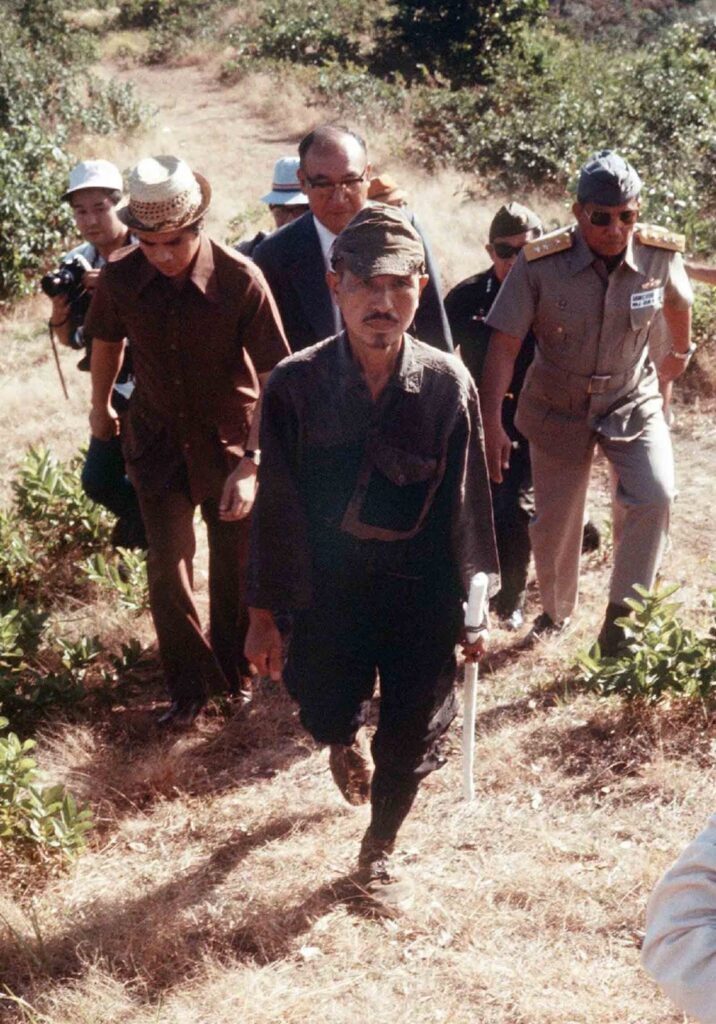

Eventually, on the 9th of March 1974, Onoda was visited in the jungles of Lubang Island by Major Yoshimi Taniguchi. Taniguchi had been Onoda’s commanding officer thirty years earlier when the war was still actually underway. He had been contacted as an individual who was best positioned to implore Onoda to surrender. Thus, when he met with his former commander in the mid-spring of 1974, nearly thirty years after his arrival on the island, Onoda agreed to surrender. He turned over his sword, his rifle, ammunition and grenades, as well as a dagger which his mother had given him in 1944 to kill himself with if the other option had been to face dishonor by surrendering. Now that he finally knew the war was over he no longer needed it.

There is a romanticized element to Onoda’s story, one which he created himself to a large extent. In late 1974, just months after his return to civilization, he published an autobiography entitled No Surrender: My Thirty-Year War, or 30 Years War on the Island of Lubang in Japanese. This detailed his wartime service and the quarter of a century of additional resistance thereafter. In this he depicted he and his fellow soldiers’ efforts as being those of a brigade of Japanese troops bound by ideas of honour and a refusal to surrender. But this is not the case. For instance, Onoda depicts himself and his fellows as targeting military sites exclusively, but the reality is that they also engaged in attacks on civilian targets and Onoda is believed to have killed approximately 30 civilians during his time in the Philippines. As such, while many people have romanticized the idea of the Japanese holdouts that refused to surrender, the reality was that these were soldiers who were ideologically committed to a brutal form of Far Eastern ultra-nationalism. When they were finally brought to surrender and the Empire of Japan began to transform itself in an astonishing way, which was mirrored in West Germany after 1945, the world was much the better for it.

The post The WWII Soldier Who Didn’t Surrender Until The 1970’s appeared first on WW2 Helmets™.

Snake Island During World War II 15 May 2022, 1:40 am

The Black Sea Island of Conflict: A History of Snake Island

Throughout history there have been islands across the world which have become centres of conflict that far outweigh the geopolitical or economic importance of the islands themselves. For instance, in ancient times the city states of Athens and Megara went to war several times over possession of the island of Salamis in the Saronic Gulf. This was a largely pointless rivalry as it made little difference to either state’s economic interests. In the early 1980s Argentina went to war (unofficially) with Britain over possession of the Falkland Islands, a largely valueless island archipelago in the South Atlantic, while China is ratcheting up tensions with its neighbors in the South China Sea today over a series of tiny islands in the region that are of negligible value. One such island which is garnering a lot of attention today is Snake Island or Serpent Island in the north-west of the Black Sea. Lying off the coast of Ukraine in a region which has seen more than its fair share of conflict over the centuries, the island has been a perennial source of rivalry since ancient times.

Snake Island, which is also known as Zmiinyi Island, is an island which lies some 35 kilometres off the coast of southern Ukraine, directly west of the Crimean Peninsula and south of the port city of Odessa. It is a tiny island measuring approximately 660 metres in length by 440 metres in width. Thus, there is only one settlement of any kind here, an outpost called Bile, which is used for various fishing and naval purposes. However, despite its relatively small size, Snake Island has some significance owing to its geographical location on the outskirts of the Gulf of Odessa and also its proximity to the mouth of the River Danube, Europe’s largest waterway. Thus, over 2,500 years ago the Greeks, who called the outcrop Leucos or White Island, built a temple here to the hero of the Trojan War, Achilles. There was also a temple to Apollo, the god of archery, music and poetry. The site was considered important as it was traditionally believed to be the resting place of the remains of Achilles and his companion, Patroclus. Later in Roman times the island continued to hold some significance for the peoples of the Mediterranean and it is mentioned by the early imperial Roman poet, Ovid, who was banished to the region around Odessa, and several Greco-Roman geographers such as Strabo and Ptolemy.

Snake Island began to become a point of conflict between local societies in Eastern Europe in the Late Medieval Period as the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea were contested by various powers such as the Ottomans, Byzantines, Genoans and Venetians, as well as nomadic people from the Asian Steppe such as the Cumans and then the Mongols who descended from north of the Caspian Sea into Eastern Europe. Thus, possession of the island changed hands many times. In the late eighteenth century it became pivotal to clashes between the Ottoman Empire and Tsarist Russia which were occurring across the north of the Black Sea and down along the eastern coast of the Balkans. For instance, during the Russo-Turkish War of 1787 to 1792 the Battle of Fidonisi, so-named after the Greek name for the island in modern times, occurred here on the 14th of July 1788. This naval battle ended in victory for the Russian fleet, as did the wider war four years later, resulting in the annexation of what is now part of southern Ukraine by Russia from the Ottomans, a portion of land which included the port of Odessa and extended the Russian border south-east to the Dniester River.

In 1853 the island became central to yet another conflict when the Crimean War broke out as an alliance of Britain, France and the Ottoman Empire tried to block the rise of Russian power in the Balkans. Under the peace terms which ended the war in 1856 Snake Island was returned to the Ottomans, however this was only a temporary measure as the island was given to Romania following its independence from the Ottomans in 1877. Thus, when Romania allied with Russia in the First World War, the Russians yet again returned to Snake Island in order to operate a wireless station there. Consequently the Turks yet again attacked the island in June 1917, although when the wider global conflict ended in November 1918 the island was eventually reconfirmed as a Romanian possession.

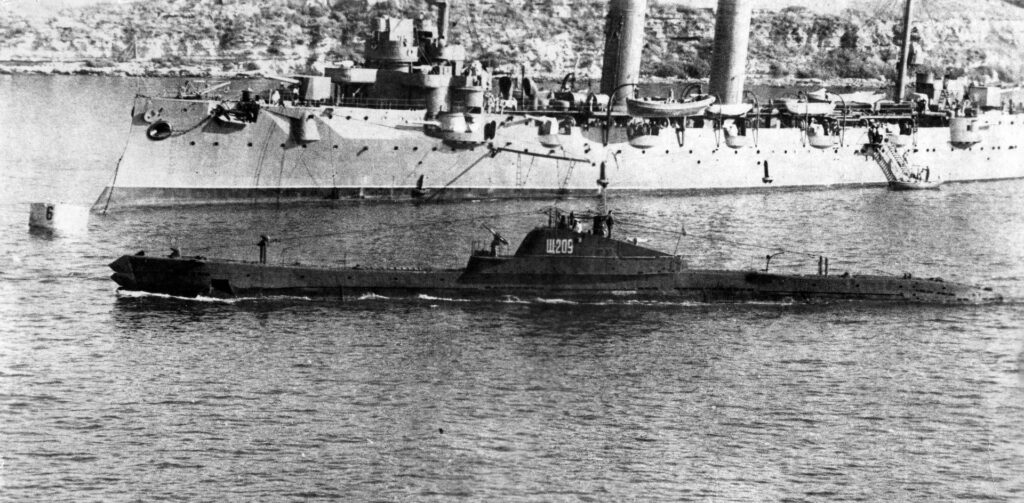

The Second World War saw Snake Island become a major source of conflict. Romania joined the Axis alliance in November 1940. Radio stations were consequently established here in advance of the German invasion of Russia and when Operation Barbarossa commenced in the summer of 1941 Romania committed more troops to aid the Germans on the Eastern Front than all of the other Axis allies combined. As a result Snake Island, which lay near the Romanian-Soviet border, became a major source of conflict during the war. Large gun emplacements were placed on the island and mines were laid down in the waters around it. Starting in June 1941 the waters thereabouts also became sources of increasing clashes between patrols of Romanian ships and Soviet destroyers, cruisers and submarines. This became particularly intense in the early winter of 1942 as the Battle of Stalingrad was raging on the mainland further to the east, becoming one of the most decisive conflicts of the Second World War. For instance, on the 1st of December 1942 a Soviet cruiser and destroyer arrived there and began bombarding the Romanian positions on the island. This resulted in damage to the radio station, barracks and lighthouse there, but the Soviets were eventually fended off. In the weeks that followed several Soviet submarines were sank by Romanian mines and depth charges in the waters around the outcrop. And this eventually convinced the Soviets to leave the Romanians in possession of the island until they were better placed to occupy it. Thus, it was not until the last days of August 1944, as Soviet troops barreled across Eastern Europe towards cities like Warsaw and Krakow, with the ultimate goal of reaching Berlin, that the Romanian marines ensconced on Snake Island were evacuated and it finally fell to the Russians.

In the aftermath of the Second World War the mainland to the west of Snake Island was ceded from Romania to the Soviet Union, and the island theoretically fell into Russian hands. However, it remained a point of contention between the Soviets and their Communist allies in Bucharest throughout the Cold War, with the result that when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 newly independent Ukraine acquired control of it. As a result, the tiny island in the north-east of the Black Sea has yet again become central to a military conflict following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Snake Island was attacked on the very first day of the war, the 24th of February, as Russia has attempted to block Ukraine’s access to the Black Sea. The attack on the island gained widespread notoriety when the Ukrainian garrison responded to demands by the crew of a nearby Russian cruiser to surrender by stating, “Russian warship, go fuck yourself.” Despite this spirited act of defiance, the island was occupied within hours by the Russians, however, as Moscow’s campaign in Ukraine faltered in the weeks that followed, the Ukrainian army engaged in tactical strikes on the Russian position on Snake Island in April 2022. Thus, expect Snake Island to continue to have a centrality to conflicts in the Black Sea completely disproportionate to its size and economic value for the foreseeable future.

The post Snake Island During World War II appeared first on WW2 Helmets™.

The Philippine Great Escape: The Raid at Cabanatuan 13 May 2022, 7:36 pm

The great majority of attention generated by the Second World War is usually focused on Europe and the Allies’ efforts to first combat German expansion and then begin rolling back their earlier conquests from 1942 onwards. This is understandable to a certain extent. After all the other great theatre of the war, the Pacific front, was deliberately made a second priority by the Allies until such time as the war in Europe had been won. Moreover, when attentions did focus on the Far East in the summer of 1945 the advent of the nuclear bomb ended the Pacific War very quickly. But the Pacific War was crucial all the same. One of the most neglected aspects of its history is efforts by the Allies to break out of Japanese POW camps between 1942 and 1945, for the war in the Pacific produced a ‘Great Escape’ that was every bit as dramatic as the escapes from European POW camps such as Stalag Luft III. This was the infamous raid on the Cabanatuan POW camp in the Philippines on the 30th of January 1945.

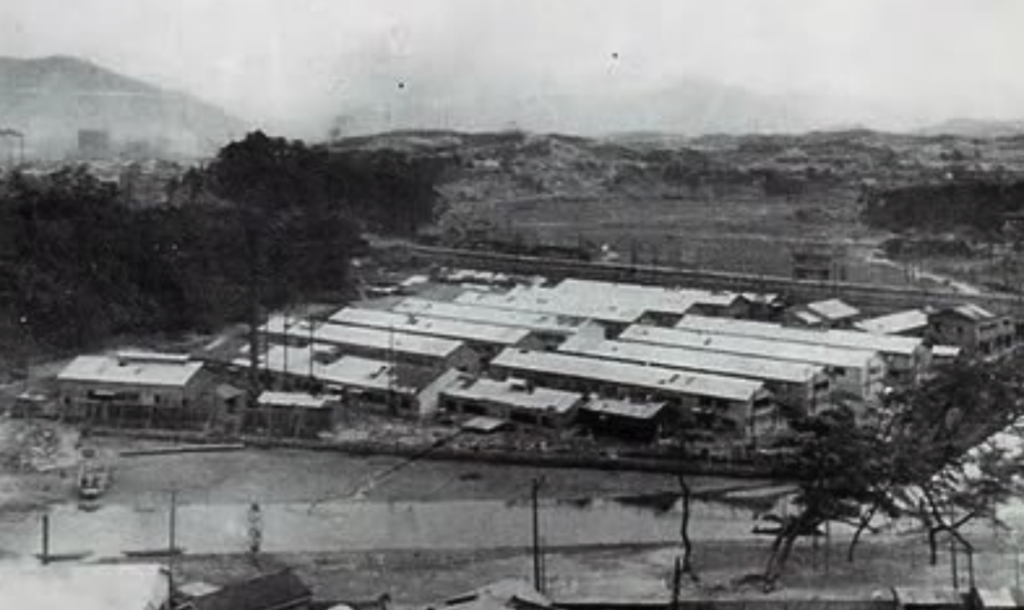

The US-controlled Philippines in Southeast Asia were attacked by the Japanese simultaneous with the strike against the American Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbour in Hawaii on the 7th of December 1941. However, while the strike on Pearl Harbour was a hit and run attack designed to destroy as much of the US’s military capabilities in the Pacific as possible before retreating back to Japan, the assault on the Philippines was sustained and had the goal of conquering the archipelago from the Americans. This was achieved in early April 1942 when the US pulled much of its forces out and the remaining remnants of their armies surrendered to the Japanese onslaught. When they did so over 70,000 American and native Filipino soldiers were captured by the Japanese. Several thousand of these were subsequently transferred to a POW camp established near the town of Cabanatuan on the primary Philippine island of Luzon. Here they would spend much of the next three years.

Conditions at Cabanatuan were severe. Thousands of prisoners had been killed in a brutal death march to the camp in 1942 and this continued thereafter with upwards of 3,000 POWs perishing at the camp between the summer of 1942 and late 1944, the result largely of severe overcrowding and outbreaks of disease. Then as the war effort turned against Japan in 1943 rations to the POWs at Cabanatuan were cut drastically. By the end of 1944 not much more than 500 POWs were still held here. Thus, when US forces invaded the island of Luzon on the 9th of January 1945 under General Douglas MacArthur, the same commander who had been in charge of the military campaign in the Philippines back in December 1941, the liberation of the Cabanatuan POW camp was made a priority. This was especially necessary as the Japanese had begun massacring POWs in other camps as they lost control of islands across the South Pacific in 1944 and early 1945.

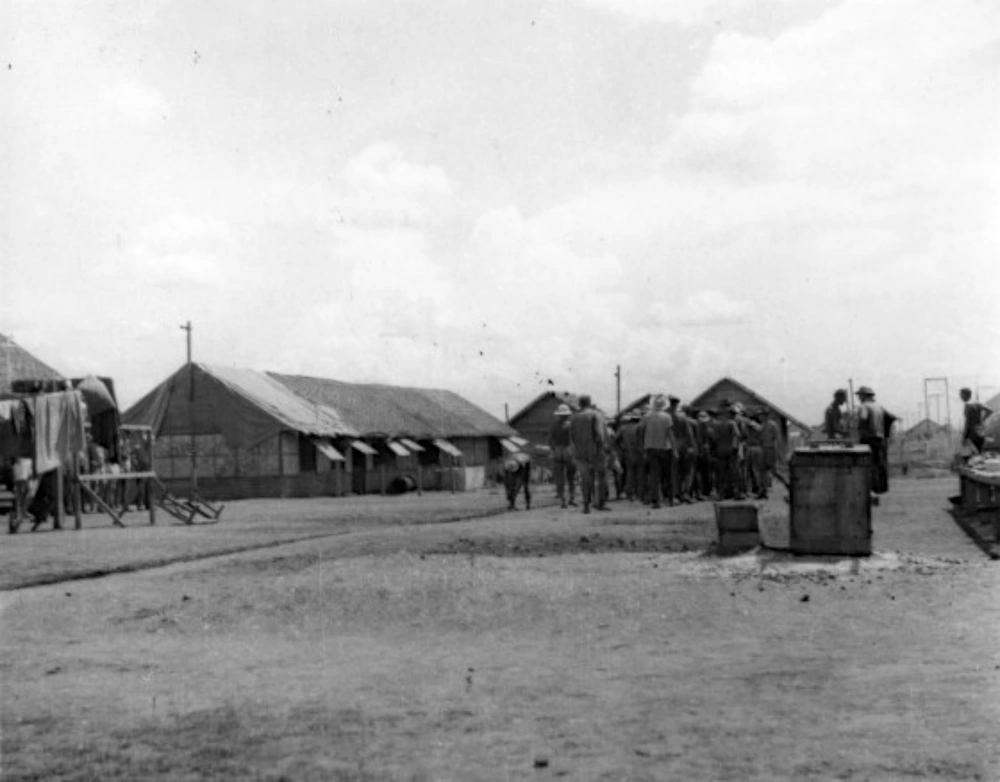

A plan was soon formulated for a raid on the camp at Cabanatuan. The 6th Ranger Battalion, which was under MacArthur’s control in the Philippines, had extensive experience of acting as special operatives behind enemy lines. As a result they were selected to undertake a stealth attack on the camp at Cabanatuan some 30 miles behind enemy lines. Just over 130 troops from the 6th Ranger Battalion would undertake the mission, aided by over 250 Filipino guerrilla soldiers. The 29th of January was fixed for the date of the Philippine Great Escape.

The 6th Ranger Battalion set off from American lines on the 27th of January towards Cabanatuan. They had extensively studied maps and charts detailing the layout of the camp and the troops there as well as the surrounding region in the days prior to setting out. Consequently they were able to proceed unmolested to within five miles of the Cabanatuan POW camp by the 29th of January where they rendezvoused with the Filipino guerrillas. At this stage, owing to news of extensive Japanese troop movements in the region, they decided to delay the raid for 24 hours. Consequently it was the 30th of January before the Raid on Cabanatuan was initiated.

The raid began when the Filipino guerrillas severed the phone lines into the camp from Manila. The two main roads leading in and out of the camp were then blocked to prevent any reinforcements arriving. Then the mission into the camp proceeded. It had been arranged for a P-61 fighter plane to fly over the camp to distract the guards with the threat of a bombing mission. The camp was guarded by just over 200 Japanese, but speed was of the essence, as there were approximately 1,000 more Japanese in the wider vicinity and if news of the raid reached the town of Cabanatuan itself there were upwards of 8,000 Japanese stationed there ready to pounce.

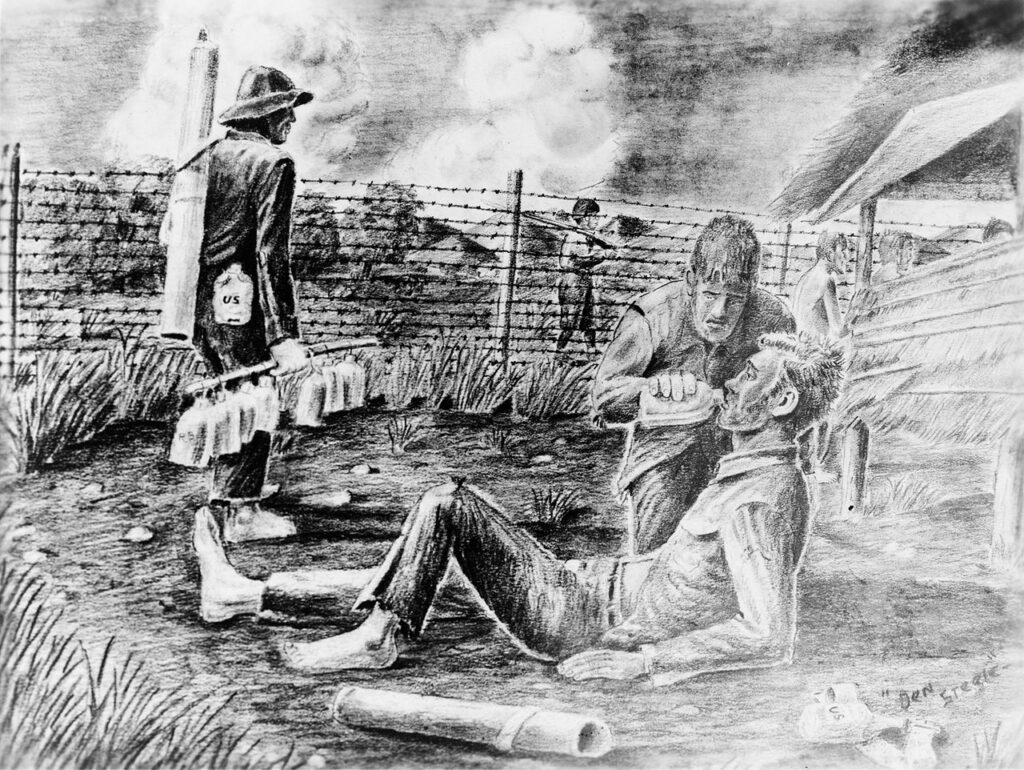

While the camp guards were briefly distracted by the flyover the 6th Ranger Battalion and some of the Filipino guerrillas crawled forwards and entered through the front and back gates of the compound. During this action the Japanese were taken completely unawares and most of the camp guards were quickly overpowered. A difficulty arose when the POWs refused to cooperate with their rescuers, briefly believing that the commotion had been caused by a retreating Japanese battalion who were intent on massacring the surviving POWs on their way through. Once the confusion was alleviated, though, the 6th Battalion and the Filipino guerrillas were able to flee the camp with over 500 POWs in tow.

By now the wider Japanese forces in the area were aware that something was occurring at the POW camp and hundreds of troops were closing in on the Americans, their allies and the prisoners. What followed was one of the most daring escapes ever achieved in the annals of military history. Over the course of the next 24 hours the 6th Ranger Battalion led their convoy all the way back towards the American lines, while under regular Japanese fire. Two members of the 6th Battalion were killed and a handful or so of Filipino guerrillas and POWs were also killed or wounded, but this paled in comparison with the Japanese death toll. Over 500 Japanese troops lost their lives during the raid, while 511 POWs were rescued in total. Thus, the Raid on Cabanatuan proved to be a far more comprehensive escape of POWs in the Pacific theatre than was generally achieved anywhere on the European front during the Second World War.

The post The Philippine Great Escape: The Raid at Cabanatuan appeared first on WW2 Helmets™.

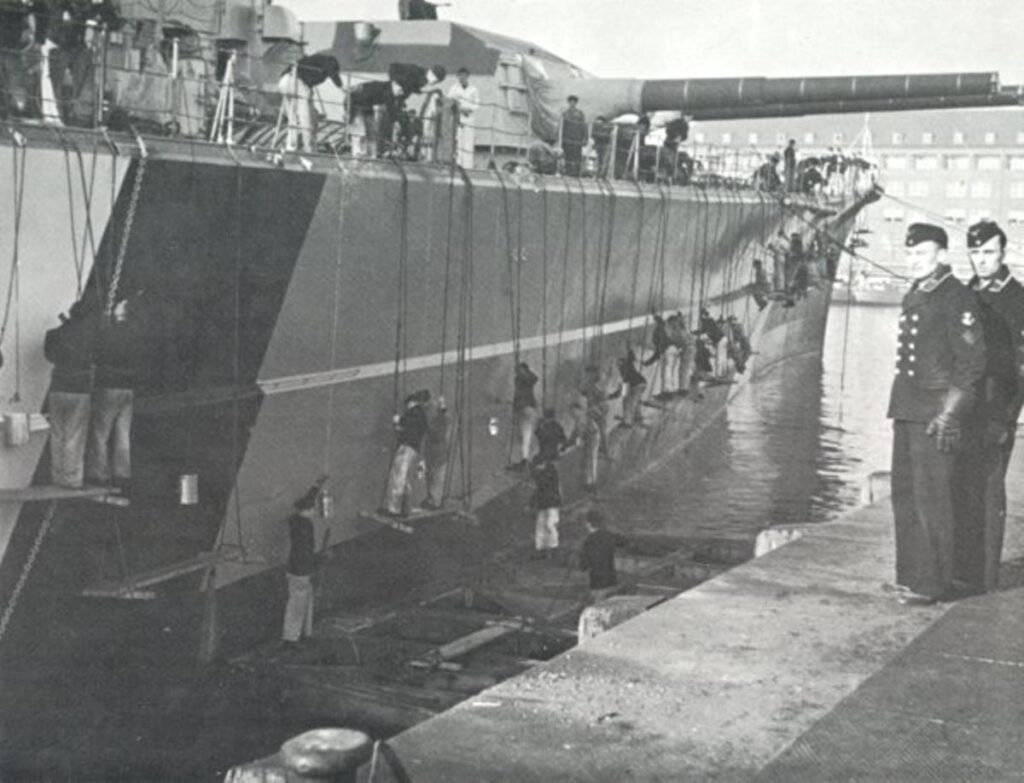

The First and Last Voyage of the Battleship Bismarck: Operation Rheinübung 6 Feb 2022, 1:45 am

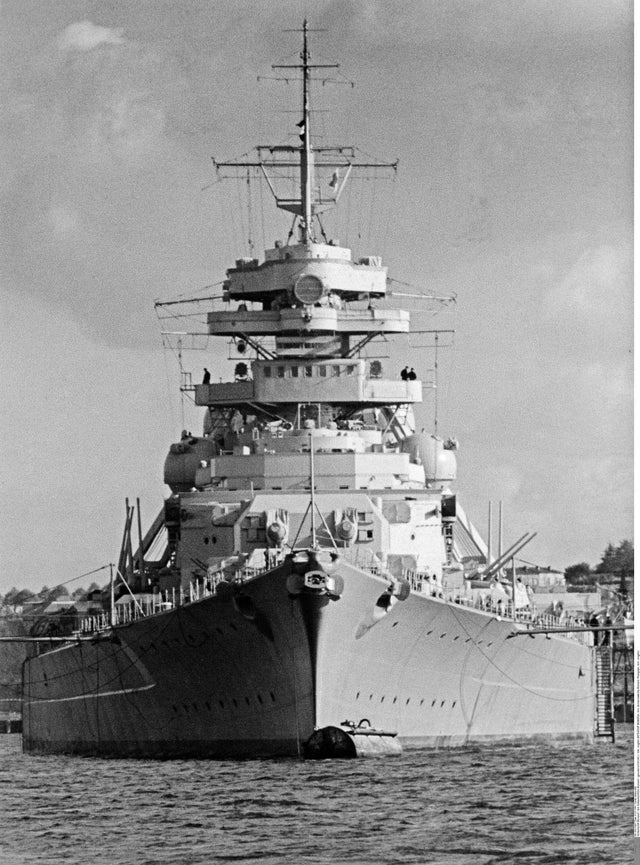

Few ships have gained as much notoriety over the years as has the Bismarck, the enormous German battleship which was constructed in the mid-1930s by the Nazis and which ended up at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean after just one active mission in the early summer of 1941. But mention of the Bismarck usually brings up images of some sort of naval folly, the German military equivalent of the Titanic, the British passenger liner which struck an iceberg off North America on its maiden voyage, or the Vasa, the Swedish flagship which sank after sailing just 1,300 meters out from port on its own first voyage after the lower gun-decks flooded with water. But it would be inaccurate to suggest that the Bismarck’s demise was owing to recklessness on the part of the captain or design flaws in the construction of the ship. Rather the German battleship was brought down because the Royal Navy pursued it relentlessly on its first active mission, Operation Rheinübung.

Construction of the Bismarck began in the port of Hamburg in July 1936 in response to the construction by France of their huge battleships of the Richelieu-class. Bismarck was one of two ships of the Bismarck-class, the other being the Tirpitz. Both the class and the ship were named in honor of the Prussian chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, who had united Germany into the German Empire in 1871 and dominated its politics in the 1870s and 1880s. When completed in 1940 the Bismarck displaced 41,700 tones and was 251 meters long. It could travel at a speed of nearly 31 knots and at maximum strength had a crew of 103 officers and 1,962 mariners. Most significantly, the ship was armed with eight 38cm SK C/34 guns arranged in four twin gun turrets, as well as four super-firing turrets, two each at the fore and aft of the ship. Beyond these primary guns the Bismarck had dozens of smaller gun turrets and twelve ant-aircraft guns. Effectively it was a floating fortress and when it was launched it was the most powerful battleship in Europe.

Although the Bismarck was launched on the 24th of August 1940 it did not immediately see service. First there were trials to be undertaken in the Baltic Sea and then poor weather and a sunken ship blocking passage through the Kiel Canal ensured that the ship could not make it back to Hamburg until the spring of 1941. Then the further launching of the Bismarck was delayed again until Tirpitz was finished and Hitler could view both ships together at the port of Gotenhafen in early May 1941. This done the Bismarck was dispatched on Operation Rheinübung, meaning ‘Exercise Rhine’ on the 18th of May 1941 under the commands of Admiral Gunther Lutjens and Captain Ernst Lindemann. It would never return to port.

The goal of Operation Rheinübung was for the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen, a German heavy cruiser, to sail out into the North Atlantic and begin attacking Allied merchant shipping as part of the Battle of the Atlantic, the effort to force Britain to surrender by bombing the country from the sky and cutting off supplies to it from the sea. The two battleships were accompanied by a flotilla of smaller ships including three destroyers, a number of minesweepers, several supply ships and a group of U-boats dispatched to intercept and try and sink any British battleships which might be sent against the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen. The flagship was, if at all possible, to avoid engagement with major battleships of the Royal Navy. The objective was to destroy as much merchant shipping as possible. However, unbeknownst to the Germans, the British code-breaking team at Bletchley Park in England had intercepted information about an attack in the North Atlantic and had dispatched extra ships and resources there in their determination to destroy the German surface fleet.

The Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen first proceeded to the port of Bergan where the Prinz Eugen refueled but the Bismarck inexplicably did not. They then proceeded out into the wider Atlantic on the evening of the 21st. First they went north towards the Arctic before swinging south-west towards the Denmark Strait which separates Iceland and Greenland. Here on the 24th of May they encountered a large British naval force headed by the battleship HMS Prince of Wales and the battlecruiser HMS Hood. In a short but highly significant exchange of fire in the twenty minutes that followed the Bismarck struck the HMS Hood with a shell and the Royal Navy ship sank in just three minutes. Thereafter the HMS Prince of Wales broke off and fled before it too was sunk. But, while the Battle of the Denmark Strait was theoretically a German victory, the Bismarck had taken damage and its forward fuel tanks were damaged. The loss of fuel from these and the decision not to refuel at Bergen when the Prinz Eugen did now ensured that the Bismarck needed to return to port within a few days. It was decided to continue heading south into the Atlantic and then swing eastwards to make for a port in occupied France.

This goal would never be achieved. The British high command was incensed when it learned of the sinking of the HMS Hood and now determined to intercept the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen. Several battleships including the HMS Ramillies, the King George V, the Rodney, the cruisers, the Norfolk and Suffolk, and the aircraft carrier, the Victorious, were soon in pursuit and the Bismarck was now hampered by having to maintain slow speeds to preserve its remaining fuel. For the next two days these ships loomed close to the German ships, with raids being conducted against the Bismarck by the Swordfish Biplanes launched off of the Victorious. Then, while they lost track of where the Bismarck was on the 25th it was re-spotted by a reconnaissance plane on the morning of the 26th of May. That evening they moved in for the kill.

At roughly 21.00pm on the night of the 26th a sortie of Swordfish Biplanes launched another attack on the Bismarck. A torpedo struck the port side of the ship, jamming the plane’s steering gear. This now caused the ship to circle and sent it in the direction of the approaching King George V and Rodney battleships. By 23.40pm Admiral Lutjens on board the Bismarck had concluded that the situation was hopeless as the ship could not be maneuvered. By then other British destroyers such as the Cossack, Sikh, Maori and Zulu had reached the scene. However, even now the British took a cautious approach, conscious of the Bismarck’s massive firepower. As such they hovered around the German battleship as a gale force wind blew through their location in the North Atlantic on the morning of the 27th of May. Occasional exchanges of fire either damaged the Bismarck’s turrets or created fires which soon put their guns out of action. With the situation hopeless, the decision was taken at around 10.00am to abandon the Bismarck and scuttle it before doing so. As it started to go down the British cruiser, the Dorsetshire delivered the final torpedo hit on the Bismarck. The ship sank around 10.40am.

In the hours that followed 111 Germans were rescued from the waters of the Atlantic by the British Royal Navy ships. An effort was made to send a U-boat division through the region by the Germans to search for survivors, but none appear to have been located. Thus, the crew of the Bismarck, which was slightly over the standard crew of 2,065, were nearly all lost in the hours following the sinking of the ship. The 111 German POWs spent the remainder of the war imprisoned. In Britain news of the sinking of the Bismarck, the flagship of the German Kriegsmarine, on its maiden voyage was greatly celebrated as a turning point in the Battle of the Atlantic.

The post The First and Last Voyage of the Battleship Bismarck: Operation Rheinübung appeared first on WW2 Helmets™.

The Man Who Volunteered To Enter Auschwitz: Witold Pilecki 19 Jan 2022, 12:59 am

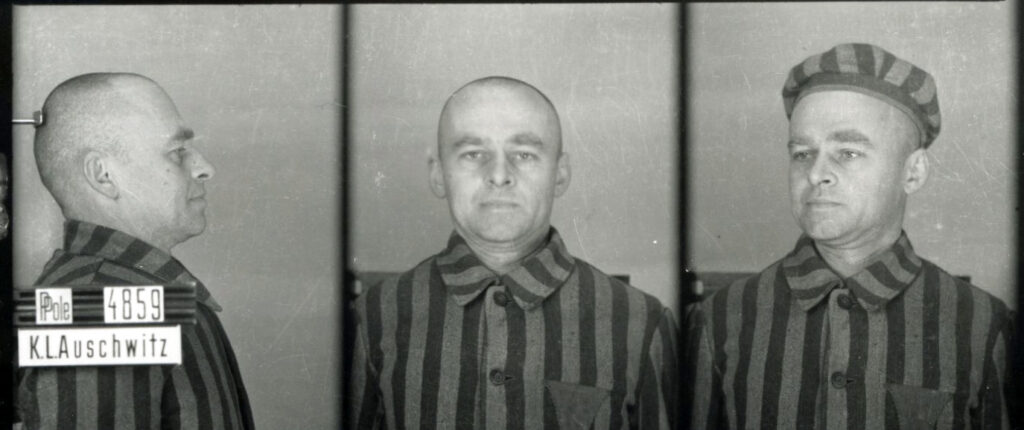

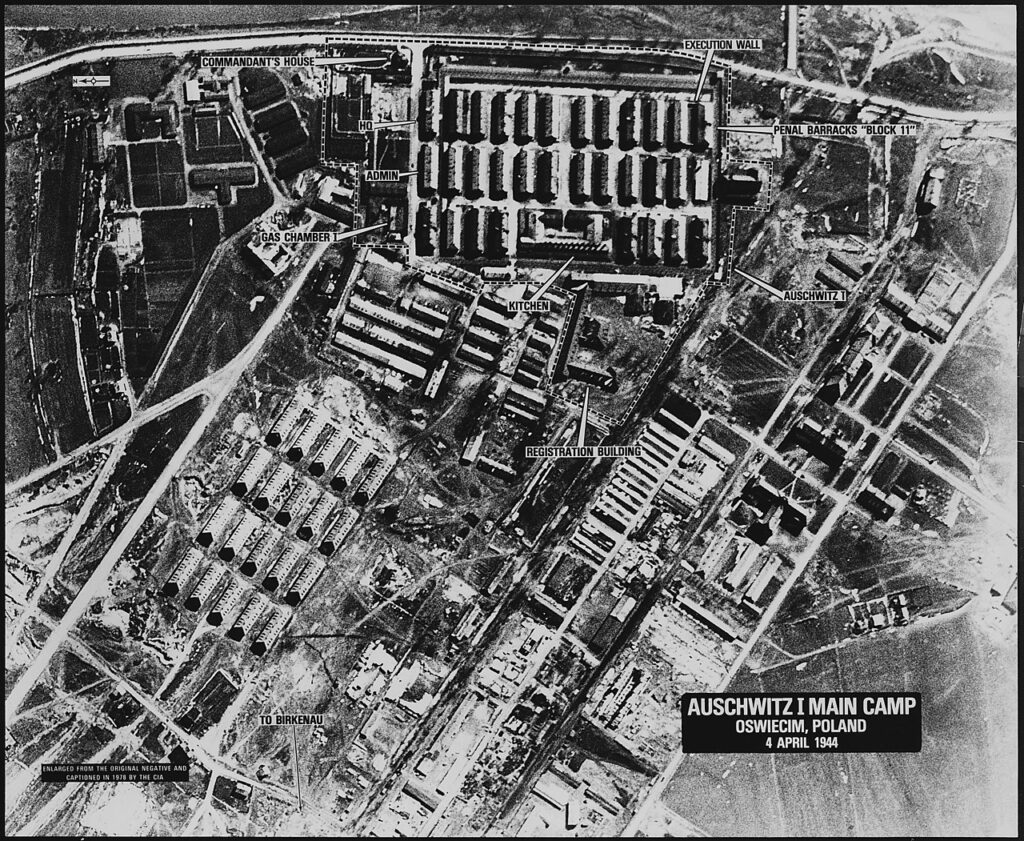

No other place has entered into the collective consciousness of humanity as being a symbol of the crimes of Nazi Germany and the Holocaust of the Jewish people which it perpetrated as has Auschwitz, the enormous concentration camp in western Poland where approximately 1.3 million people were killed between 1940 and early 1945. Most were Polish and Hungarian Jews who were intentionally murdered shortly after their arrival there, while hundreds of thousands were worked to death as slave labor. Auschwitz was clearly a place one avoided being sent to as a detainee at all costs. It is then remarkable to find that one individual, a Polish resistance leader, actually volunteered to be captured and sent here in 1940. He subsequently spent three years as an inmate at Auschwitz, during which time he organized an internal resistance movement and sent the Allies reports on conditions in the dreadful setup found there. This is the story of Witold Pilecki.

Witold Pilecki was born in the town of Orelia in Karelia in Russia in May 1901. His family hailed from a Polish noble family which had consistently resisted Russian rule in the part of Poland which had been swallowed up by Tsarist Russia during the partitions of Poland in the late eighteenth century. As a consequence Pilecki’s family had been deported to Russia proper in the nineteenth century, but they never lost their strong sense of Polish nationalism. As a result Pilecki fought for the Polish Second Republic following its formation in 1918 as part of its involvement in the wider Russian Civil War. He subsequently rose within the Polish military and continued in that role during the interwar years of the 1920s and 1930s. Thus, when Nazi Germany invaded Poland in September 1939 Wilecki fought in the brief war of occupation and quickly joined the Polish Resistance movement in its aftermath. It was in this capacity that he would volunteer to enter Auschwitz the following year.

Originally Auschwitz concentration camp was established as small labor camp on the site of a former Polish army barracks in Silesia in western Poland early in 1940. The first loads of prisoners began arriving in the early summer. However, what started as a small labor camp quickly expanded in the course of late 1940 and early 1941 into a vast complex consisting of three camps. Auschwitz Camp 1 was the main administrative and labor camp, where the German officers and staff also lived. Camp 3, known as Auschwitz-Monowitz, was eventually set up as a slave labor camp, primarily to produce synthetic rubber through the IG Farben chemical company. But the camp is most infamous for Camp 2, Auschwitz-Birkenau, which was effectively a death camp where, beginning in the autumn of 1941, hundreds of thousands of individuals were gassed to death using prussic gas or Zyklon-B and then had their bodies cremated on site. At its peak in the summer of 1944 when half of Hungary’s Jewish population of 750,000 people were killed at Auschwitz in the space of just five months, upwards of 5,000 people were being killed and cremated at Auschwitz-Birkenau every day.

This was the place Pilecki volunteered to enter in August 1940, the Resistance movement in Poland needing details on the new camp and what it would be used for. It was arranged for him to be arrested by the Germans on the 19th of September 1940 as part of a wider group of some 2,000 Polish political prisoners. He carried papers at this time which identified him as a Tomasz Serafinski. Within days he had been sent to Auschwitz where he was admitted as prisoner number 4,859, an indication of exactly how small the camp was at this early stage.

Pilecki would spent three years at Auschwitz, during which time it expanded from a small labor camp and detention center of Polish political prisoners, to one of the most horrendous death camps run by the German SS across Europe. Throughout these years he drew up numerous reports on the conditions within the camp and the increasing level of mass murder being orchestrated by the Nazis there. These were smuggled out to the Polish resistance movement. By 1942 Pilecki was able to provide approximate details of the numbers of people being killed there. Additionally he was involved in efforts to expand the resistance movement amongst Auschwitz’s many tens of thousands of inmates. Plans were once even being considered to lead an internal rebellion aided by external support from the Polish Resistance and in 1942 Pilecki and his network of allies within the camps even succeeded in setting up a radio station inside Auschwitz which for a period even managed to broadcast reports to the Polish Resistance movement throughout the wider country.

Pilecki did all of this at considerable risk to his own personal well-being. Because of the appalling conditions in the camps disease and malnutrition were rampant there and he once survived a bout of severe pneumonia while at Auschwitz. However, as time went by the greater threat came from the SS and the Gestapo, which were aware that there was an internal resistance movement of some kind operating within the camp. As these sought to uncover the ring-leaders Pilecki eventually decided to escape in the spring of 1943 before he was identified and executed as being a major orchestrator of the unrest. Thus, after being assigned to a night shift at the camp bakery on the night of the 26th of April 1943 he and two others managed to escape by overpowering a guard and escaping beyond the perimeter of the camp. Having finally escaped he reconnected with the Resistance movement and produced a comprehensive account about Auschwitz called Witold’s Report which provided further intelligence to the Allies about what was occurring in the metropolis of death which Auschwitz had become.

There is no doubt that Witold Pilecki was a war hero. And yet he would not be commensurately honored in the aftermath of the Second World War. As the conflict with Germany drew to a close Poland was yet again subsumed by Russia. In the years that followed a Polish communist state, which was effectively a puppet of Moscow, was established. Pilecki was soon a part of a new Polish resistance movement to oust the Russians from his country. By 1946 he had been ordered to leave Poland or face prosecution. He refused and in May 1947 he was arrested by the communist authorities. A show trial followed a year later, by which time Pilecki had been tortured on several occasions, but he had steadfastly refused to provide information about others in the new resistance movement. He was quickly found guilty and executed in Warsaw later that month, despite the attempts of many former inmates of Auschwitz to plead for clemency on his behalf. Thus died the man who volunteered to enter Europe’s most brutal concentration camp under Nazi occupation, but several books and accounts of his career in the years since have ensured that Witold Pilecki’s story is not forgotten.

The post The Man Who Volunteered To Enter Auschwitz: Witold Pilecki appeared first on WW2 Helmets™.

Disinformation Behind Enemy Lines at the Battle of the Bulge: Operation Greif 28 Dec 2021, 1:26 am

The winter of 1944 saw Nazi Germany undertake its last offensive campaign of the Second World War. The Battle of the Bulge was undertaken in the heavily forested Ardennes region straddling Belgium and Luxembourg in December 1944. The goal here was to launch a surprise counter-attack against the advancing US 12th Army Group and the British 21st Army Group as they prepared on the borders here for a springtime offensive into the Rhineland region of western Germany. The Ardennes Offensive would involve German Army Group B consisting of the 7th and 15th Armies and the 5th and 6th Panzer Armies surging westwards in a fashion which resembled a bulge on maps days into the offensive and attempting to then circle back around and encircle the Allied forces. If they could be cut off and made to surrender, along with the Allied use of the port of Antwerp being interrupted, it was hoped that the Allies might decide to try to negotiate peace terms favorable to Germany. Alternatively, it might extend the duration of the war for long enough for the Western Allies to fall out with the Soviet Union.

The story of the Battle of the Bulge is well-known, but a more obscure aspect of it was Operation Greif, through which the German high command hoped to create chaos in the Allied ranks in the Ardennes region by spreading misinformation and if possible to secure a bridge over the River Meuse in the area. The Allies would attempt to destroy these bridges as soon as the Ardennes Offensive began, so it was important that one would be secured over the river which German armored units could then use to quickly traverse the river in the first hours and days of the campaign.

Operation Greif was to be headed by Otto Skorzeny, an Austrian born member of the Waffen-SS who had been heavily involved in several commando missions during the war, most notably the daring rescue of Benito Mussolini from a mountainside hotel in 1943 when he had been displaced as the leader of fascist Italy. Now Skorzeny was placed in charge of the new covert operation in the Ardennes region. The plan was relatively simple. Skorzeny would form a unit of special operatives to be known as Panzer Brigade 150. These men would wear American army uniforms and use captured American vehicles to disguise themselves as Allied troops. They would then secure a bridge over the River Meuse and begin undertaking other actions to create confusion amongst the Allied troops in the area.

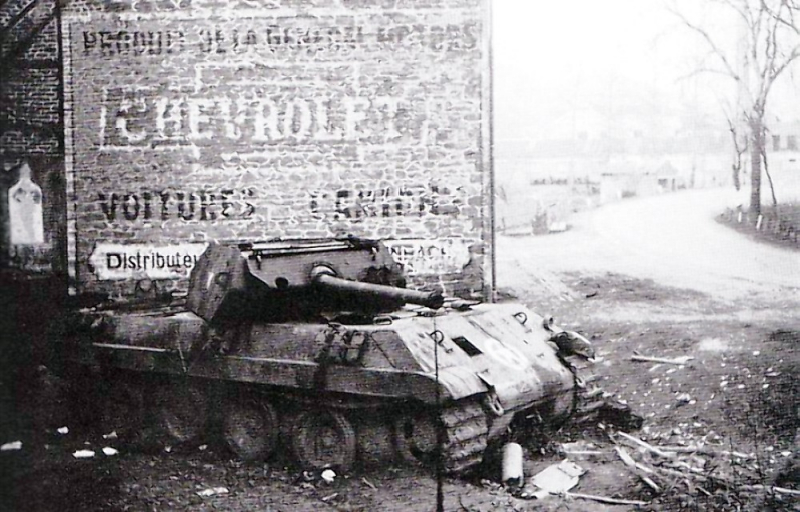

The Ardennes Offensive was to be launched on the 16th of December 1944, so when Skorzeny received his directive in late October he had only a few weeks in which to prepare. There were several obstacles to be overcome. He needed soldiers who could not just speak English, but do so in a passable American accent. It had originally been intended that he would identify well in excess of a thousand such men. Scores of American vehicles and tanks were also sought, but in the end Skorzeny could only put together a fairly rag-tag unit. Some of the men had barely passable English and the vehicles consisted largely of just trucks and jeeps. Only one American Sherman tank was located and in the end they resorted to disguising German Panzers as M10 Tank Destroyers. Consequently a very small force was eventually assembled. As a result, it would only be a motley crew of several dozen English-speaking commandos who headed behind enemy lines in the Ardennes region in early December 1944 as part of Operation Greif.

Despite the logistical and technical problems which bedeviled the operation, Operation Greif created chaos when it was launched on the 16th of December. Skorzeny’s men had orders to destroy fuel depots and ammunition dumps to inhibit the movements of the Allied forces in the Ardennes. They also moved road signs to send the Americans and the British in the wrong directions. If they encountered Allies units the commandos who had fluent English and passable accents would pass on bogus orders and misinformation sending entire units off in the wrong direction. They were also sabotaging telephone lines and radio stations to cut off communications between the Allies.

By the 17th of December it was clear that Panzer Brigade 150 would be unable to seize one of the bridges on the River Meuse. Accordingly Skorzeny, who was commanding the unit from behind German lines, requested that they be allowed to continue their sabotage efforts and try to attack targets in a more conventional sense from behind enemy lines, a request which was granted. Months later, when he was captured by the Allies, Skorzeny provided an account of much of this activity and described how his men sent entire Allied regiments in the wrong direction and convinced other units that they had been ordered to withdraw from villages in the Ardennes.

Within a few days it was clear to the Allies that there was a German brigade disguised as American troops operating behind their own lines. As a result American soldiers now took to stopping units they didn’t know and asking them questions which they believed only Americans would know the answers to. This resulted in serious disturbances itself, as some American troops were fired on in the belief they were the incognito German troops. There was a farcical element to it too though. The famous British general, Bernard Montgomery, had the tires of his jeep shot out by some over-zealous American GIs, while General Omar Bradley was briefly detained by an American soldier after answering Springfield at a US checkpoint when asked what the state capital of Illinois was. The soldier had the wrong answer to his own question and had believed Chicago was the Illinois’s state capital.

The confusion created was probably the greatest success of Operation Greif. By late December it was determined to withdraw the last of the disguised troops who had been sent behind enemy lines. Several had been captured by that time and were quickly tried and shot by Allied troops in late December and early January. By then the entire German counteroffensive was failing. While the Allies had initially been taken by surprise in mid-December, on the 26th of December General George Patton, by some estimates the most strategically gifted of the Allies’ generals, though a controversial figure, arrived with the US Third Army to relieve the German attack on the town of Bastogne. By early January the Allies were on the offensive again. Nevertheless, the Battle of the Bulge had been the sharpest action of the entire war on the Western Front. With 19,000 deaths and 70,000 more men wounded it was the single bloodiest battle fought by the American during the Second World War.

The post Disinformation Behind Enemy Lines at the Battle of the Bulge: Operation Greif appeared first on WW2 Helmets™.

The Bloody Escape At Amiens: Operation Jericho 20 Dec 2021, 9:33 pm

The Second World War witnessed many great escapes of resistance fighters from occupied countries and Allied prisoners of war from German controlled territory across Europe. The most famous was surely the ‘Great Escape’ from the Stalag Luft III POW camp. Others were carried out, attempted or just planned and there was an entire department in England which was dedicated to manufacturing watches with hidden compasses, silk maps that could be placed in domino pieces and weapons masquerading as pencils. These were smuggled into the POWs in care packages. All of it was in aid of carefully planned, clandestine escape attempts. But some escape attempts were less subtle and simply involved brute force. Surely the greatest of these particular ones was the Allied endeavor in February 1944 to get hundreds of French resistance fighters out of Amiens detention center by bombing one end of the prison. It was called Operation Jericho.

The context in which this occurred was the increased planning for the opening of an Allied Western Front in France. In the course of 1943 as Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin deliberated on where this should be initiated, Allied reconnaissance of northern France increased and more and more French resistance fighters were being deployed in the area to try to get a good sense of where the Germans were strongest and where they were weakest. In particular the Allies needed detailed info on the Atlantic Wall of German defenses along the French coast. As French espionage efforts across German-occupied northern France increased so did the activities of the German secret police, the Gestapo, to try to locate French resistance fighters. Thousands of arrests were carried out in the autumn and into the winter of 1943. These included Roland Farjon and Raymond Vivant, two prominent figures in the Organisation Civile et Militaire, one of the foremost French resistance movements. Farjon and Vivant had been sending detailed info to London on German military installations, so when MI6 learned that these were being held at Amiens prison in northern France, and that many of the leading Resistance figures at Amiens would soon be executed by the Germans, they decided to act to get them and many others out.

Amiens prison was a large German-run detention center in the Picardy region. A machine gun turret adorned the yard of the prison which meant that a frontal assault by some infantry parachuted in to the region was suicide. Instead it was decided to launch an air assault using 19 of the fast Mosquito light fighter-bomber planes which had entered service in late 1941, accompanied by 14 Typhoon fighters as an escort. These would fly in at a very low altitude to bomb the guard stations and parts of the prison wall. Information on the layout of the jail had been obtained through the Resistance and there was an exact idea of where needed to be hit. If this was accomplished it was believed that a path out of the prison would be cleared and the reverberations from the bombing would trigger the cell doors within the prison to open. The Resistance network had ensured that many of the inmates were aware of the plan and waiting for the cue to move. Meanwhile, further Resistance fighters in the region had been supplied with extensive arms and ammunition and would be lying in wait very near the jail to arm those who were making their escape as soon as they got out. With all this in place Operation Jericho was scheduled for the 17th of February 1944.

When the 17th came the mission was delayed because of heavy snow and bad weather which would have made visibility very poor. This persisted into the following day, but it was determined at this point that the Resistance fighters in place around Amiens couldn’t wait any longer and the mission had to proceed. Thus, 19 Mosquito bombers were launched at about 11am, the plan being to hit Amiens at midday while the guards there were at lunch and congregated together in a specific place. They were soon joined in the sky by 11 Typhoons, but three others had been forced to abandon the mission as they lost the main formation owing to the bad weather. As they flew in over France they were reportedly flying at such a low altitude to escape radar detection that the planes were dangerously close to scraping the tops of the trees below.

They flew in over the prison at exactly one minute after 12. Over the next ten minutes the Mosquitos circled round several times, bombing the guardhouse and focusing their efforts on creating a breach in the eastern wall of the prison. Time was of the essence. Several Luftwaffe bases were in the near vicinity and their fighters were quickly scrambling to get into the air. By the time the wall was breached about 12.15 most of the Mosquitos were being closed in on by German Fw 190s. They made their escape as the Resistance fighters started to escape below, but two fighters and two bombers were lost.

Down on the ground the prisoners were making their way to the breach. Hundreds were attempting to get out, but the air raid could only be so successful. While several of the German guards had been killed in the bombed guardhouse, others were reacting and getting ready to shoot the inmates as they made their way across the courtyard. In the end, of the 832 prisoners who were being held at Amiens, 255 of them escaped in the hour following the opening of the breach in the wall. However, even of those who made it out, only 73 made it fully away. 182 were rounded up and re-imprisoned in the hours and days that followed. Yet, although less than 10% of the prisoners escaped fully, it was significant that they did. Based on the circumstances under which they had first been apprehended, these men were able to reveal details of who the Gestapo was using as informers throughout northern France.

Overall Operation Jericho was a success. It resulted in 73 Resistance fighters escaping from Amiens and the information they provided damaged the German intelligence gathering network in northern France in the weeks ahead during a critical phase in the planning of the D-Day invasion. Some debate later emerged as to who had actually ordered the mission and what the exact purpose of it was. It might well have been the case that in undertaking the mission the British had hoped to further suggest to the Germans that the coming invasion would take place close to Calais and the Picardy region in which Amiens was located. If so, the ploy worked. When the D-Day landings started just over three months later on the 6th of June the Germans had concentrated their defensive build-up around Calais, rather than at Normandy where Operation Overlord was eventually implemented.

The post The Bloody Escape At Amiens: Operation Jericho appeared first on WW2 Helmets™.

The Other Allied Invasion of France: Operation Dragoon 17 Dec 2021, 11:55 pm

The Allied invasion of northern France with the D-Day landings of the 6th of June 1944 has understandably been focused on as a major episode in the Second World War, as the long-awaited Western Front was opened in Europe. But the campaign in Normandy often completely overshadows events elsewhere, notably the fact that the Western Allies had already opened a Southern Front in Italy in the summer of 1943. But above all, the D-Day landings have resulted in the other Allied invasion of France, in the south of the country in August 1944, being completely forgotten about. This was an incredibly successful initiative and had a major impact on the speed of the Allied advance through France in 1944 and the supply of the troops there.

Deliberations on a possible invasion of southern France were underway as early as 1942 and in the course of the subsequent planning for the D-Day landings it was decided that an operation on the Mediterranean coast of France would be undertaken on the exact same day. However, this plan was dropped when it was determined to be logistically impossible to launch both at the same time. Additionally Winston Churchill was more anxious to expand the front in Italy or open a new one in the Balkans as he was seeking at this stage to prevent all of Eastern Europe falling into Soviet hands. Consequently for a time it seemed that the invasion of southern France would not be followed through with at all. What changed is that in the days and weeks following the Allied capture of northern France it was determined that the northern ports there would soon be unable to handle the level of supplies which would need to arrive through them in order to keep the ever-growing number of Allied forces supplied in France. Consequently, the plan for opening a southern front in France itself was resurrected and was quickly renamed as Operation Dragoon. It would be launched just over two months after the D-Day landings.

The goals of the operation were clear. Firstly, the main aim was to secure the ports of Marseilles and Toulon. Forces would land along the Cote d’Azur between Antibes and Cap Benat. This area was weakly defended by the Germans and the Allies had territory nearby from which to launch the operation, having secured Corsica in the autumn of 1943. In addition Allied air support would be able to bomb the region in advance of the landing in order to facilitate the ground invasion.

The Allied force for the initial landing consisted of 150,000 men, though the full invasion force which eventually flooded into southern France rose to over 575,000, primarily consisting of the American Sixth Army Group and Seventh Army. They would be supported by about 75,000 Free French or French resistance fighters. Facing them would be Army Group G of the German Wehrmacht and other units such as the 19th Army. These were commanded by Johannes Blaskowitz and in total had somewhere between quarter of a million troops and 300,000 spread across southern France.

Operation Dragoon commenced on the 15th of August 1944 with landings of an initial force of well over 100,000 personnel on numerous beachheads and sites along the coast between Cavalire-sur-Mer and Saint Raphael, the main force disembarking around Saint Tropez. Unlike in Normandy two months earlier, the Allies faced very little resistance and successfully secured the coast along here within 24 hours with very few casualties. A counterattack was mounted by the Germans on the 16th, but it failed to drive the Allies back into the sea. Then, with a large concentration of German forces endangered in the north of the country at Falaise, in what eventually became the decisive battle of the Normandy campaign, Hitler rowed back on previous orders that Army Group G was to fight for every foot of land in southern France. Blaskowitz was now given permission to make an orderly retreat north.

The retreat commenced on the 17th and 18th of August, as the Germans headed north towards the Rhone, skirting the border with Switzerland. As they did the Allies made rapid advancements themselves. On the 20th and 21st their forces arrived to Toulon and Marseilles, the primary targets of the whole operation. Here they faced small, but entrenched garrisons which had been left in the south to hold the ports for as long as possible. They held out for just one week. Toulon was liberated on the 26th of August and Marseilles on the 28th, just days after the liberation of Paris in the north on the 25th. Nearly 30,000 German troops were taken prisoner when the two southern ports surrendered.

With the south of France in Allied hands, the new objective was to try to cut off Army Group G and the others German division in their retreat northwards. Simultaneously, German garrisons further to the west in south-western France were ordered to abandon this part of France and head north-east to join up with Blaskowitz’s forces on their way to the new German line in eastern France. Small garrisons were left behind in the towns and ports of this region, some of which were still in place until May 1945 as the Allies determined that it was better to avoid bloodshed in retaking ports such as La Rochelle and Saint Nazaire when they would simply surrender once the wider war was won. This was a policy which was followed elsewhere and much of the Netherlands was also left to the Germans until war was at its end.

The Allied pursuit of Blaskowitz’s Army Group G continued into September as the Germans headed ever further north. But by the middle of the month the American Third Army was beginning to be spread thin and far away from its supply lines. Accordingly, when Blaskowitz initiated a counter-attack on the 18th of September he was able to push the Allied advance back to Luneville to the west of Strasbourg and not far from the German border. What lay ahead was a different campaign which would play out in the winter of 1944. Thus, Operation Dragoon is typically deemed to have ended on the 14th of September as the Germans made their final retreat up the River Rhone. By then the Germans had suffered relatively few casualties, with only 7,000 dead and slightly over 20,000 wounded, but over 130,000 German soldiers had been captured at various locations across southern France.

Dragoon was unquestionably a major success for the Allies. Southern France was liberated in just four weeks and the major ports there such as Toulon and Marseilles were now available to increase the flow of supplies to the Allies on the Western Front, a necessary development as the advance in the north of the country had slowed by August as supply lines there became overly stretched. This was remedied with the success of Operation Dragoon and by October 1944 one-third of all Allied supplies in France were arriving through the southern ports. Additionally, the invasion had resulted in the capture of over 130,000 German soldiers, men who might have been used to bolster the German counter-offensive at the Battle of the Bulge in the winter of 1944 if they had been able to retreat successfully back to Germany. As such Operation Dragoon, though Churchill and many others amongst the British high command viewed it skeptically at the time, must be perceived as a major Allied success during the war.

The post The Other Allied Invasion of France: Operation Dragoon appeared first on WW2 Helmets™.