Add your feed to SetSticker.com! Promote your sites and attract more customers. It costs only 100 EUROS per YEAR.

Pleasant surprises on every page! Discover new articles, displayed randomly throughout the site. Interesting content, always a click away

The Mariners' Museum and Park

One of the nation's largest privately owned and maintained parks. Free and open to the public.Drewry’s Bluff After Action Report 4 Apr 2025, 7:48 pm

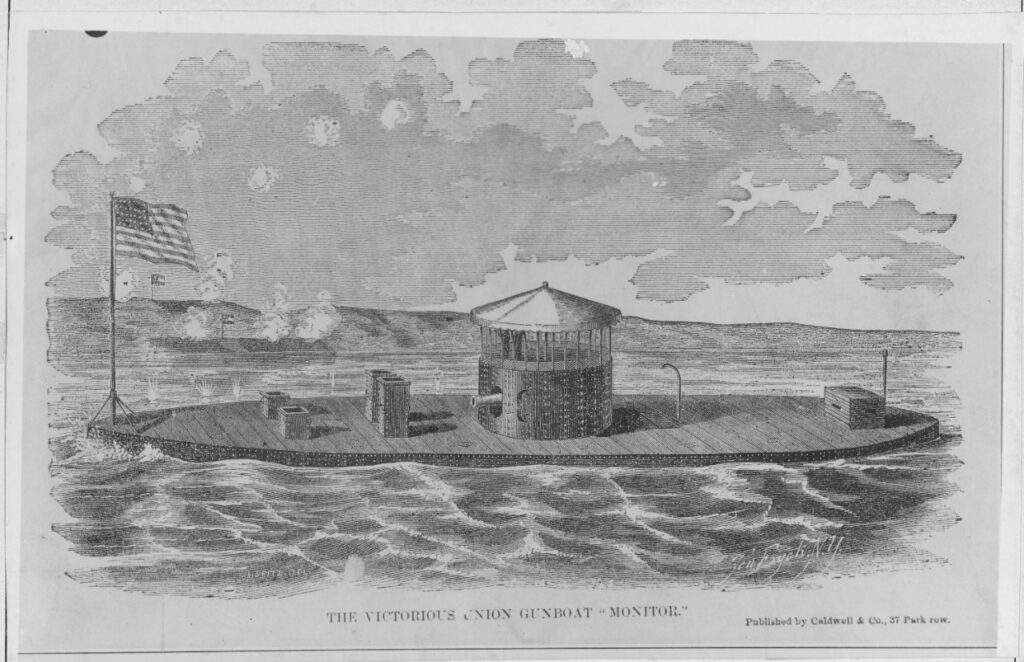

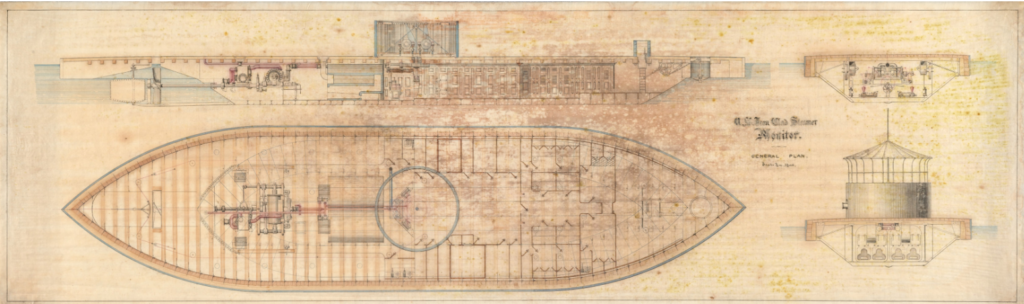

The James River Flotilla’s defeat at Drewry’s Bluff was caused by a myriad of factors. The Confederates had obstructed the James River and constructed gun emplacements atop the 90-foot-high Drewry’s Bluff. Plunging shot from this fortification badly damaged USS Galena. USS Monitor proved not to be a factor in the battle. Consequently, the Union flotilla was forced to fall back downriver. They had come within eight miles of Richmond; yet, the Confederate capital remained out of the Union’s reach until 1865.

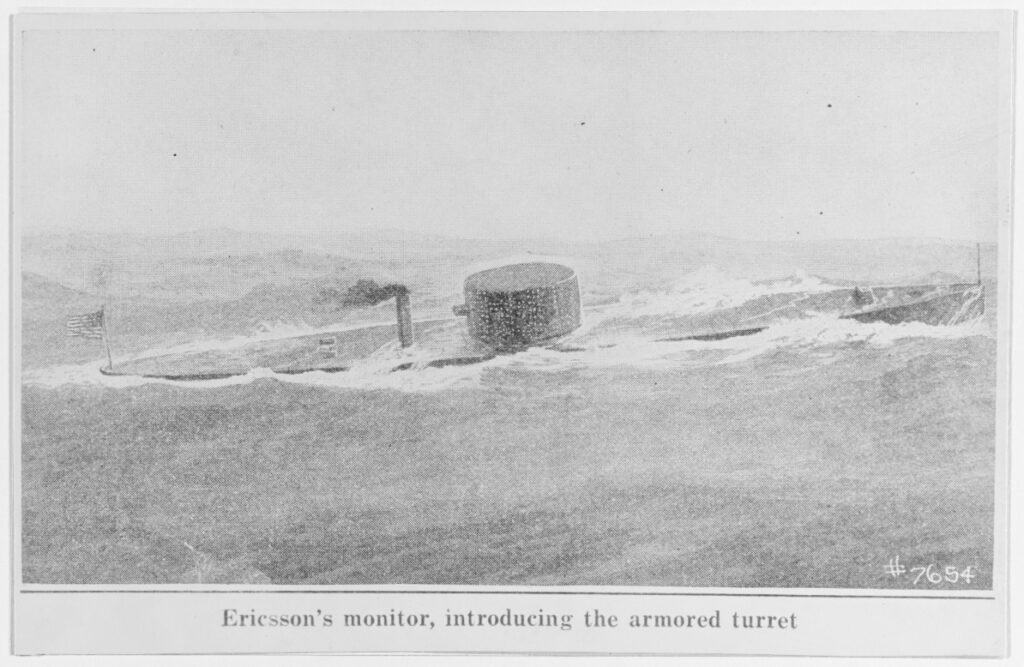

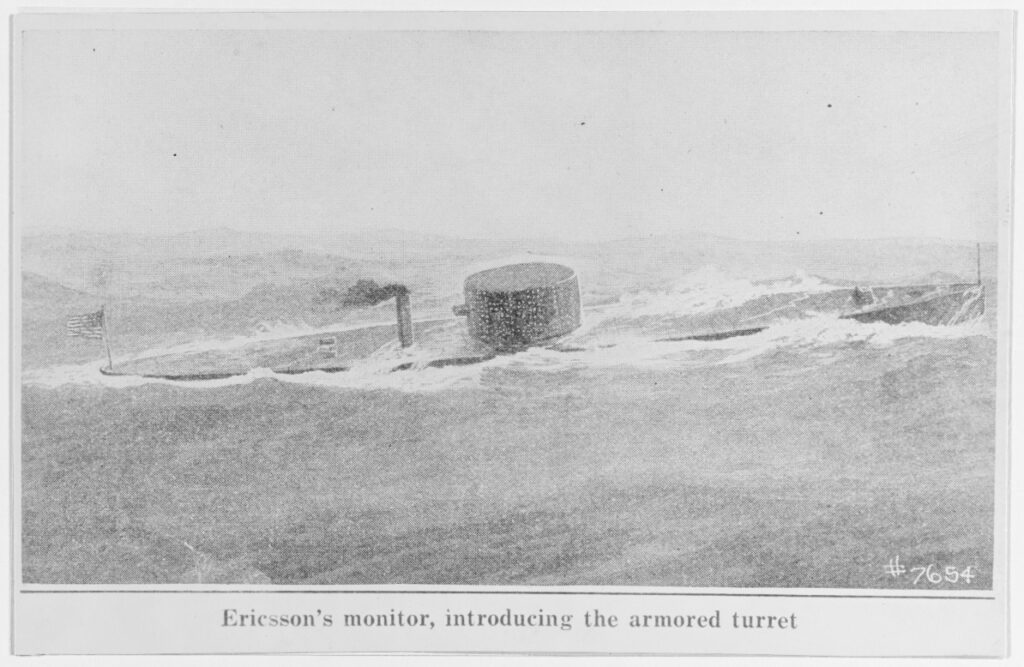

The battle was really a test between ironclads and fixed fortifications. Commander John Rodgers had already expressed his contempt for USS Galena. Eventually, this gunboat would have its armor removed and would serve as a wooden warship during the August 1864 Battle of Mobile Bay. As for USRCS Naugatuck, it was never accepted by the US Navy. Most of the public really wanted to know how USS Monitor fared during this engagement. After all, it was the “little ship that saved the nation” on March 9, 1862. The ironclad seemed flawless; however, Drewry’s Bluff would make the ship appear otherwise.

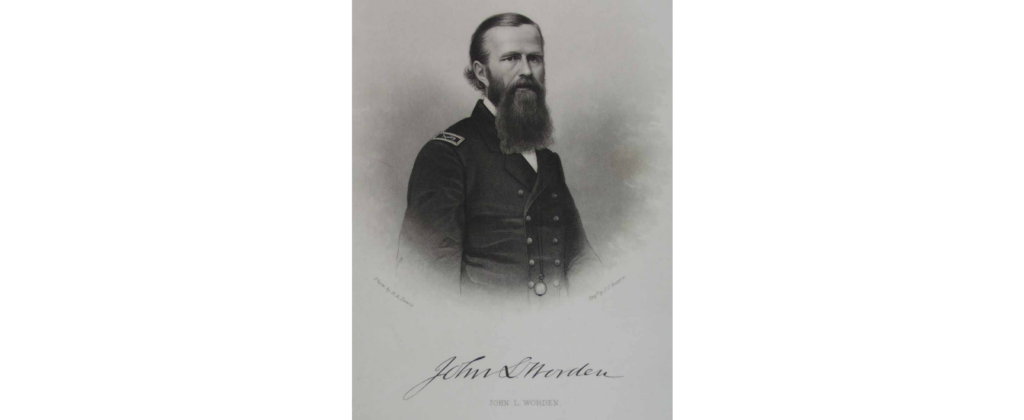

Lieutenant John Worden had already met with President Abraham Lincoln and told him about some of the ironclad’s weaknesses as he lay in bed recovering from his wounds received during the March 9 battle. Worden noted that the warship was unseaworthy and had a limited rate and range of fire. Monitor’s former commander expressed his fears that the ironclad could be boarded and captured. President Lincoln would then advise Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles not to expose the ironclad to close combat. (1)

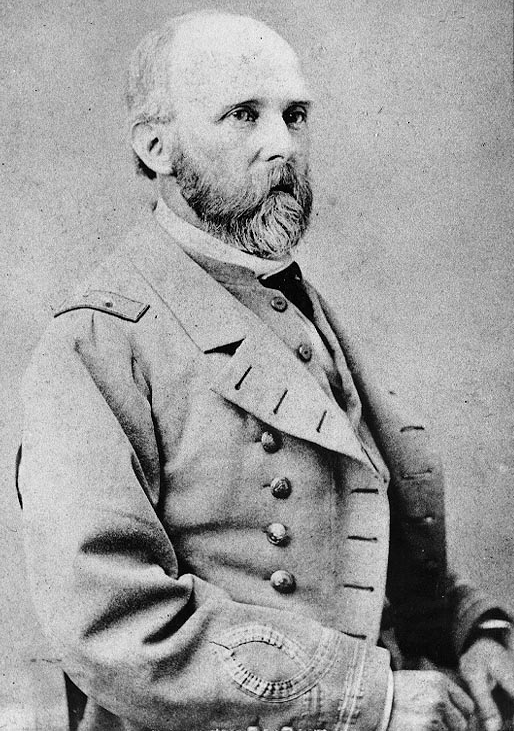

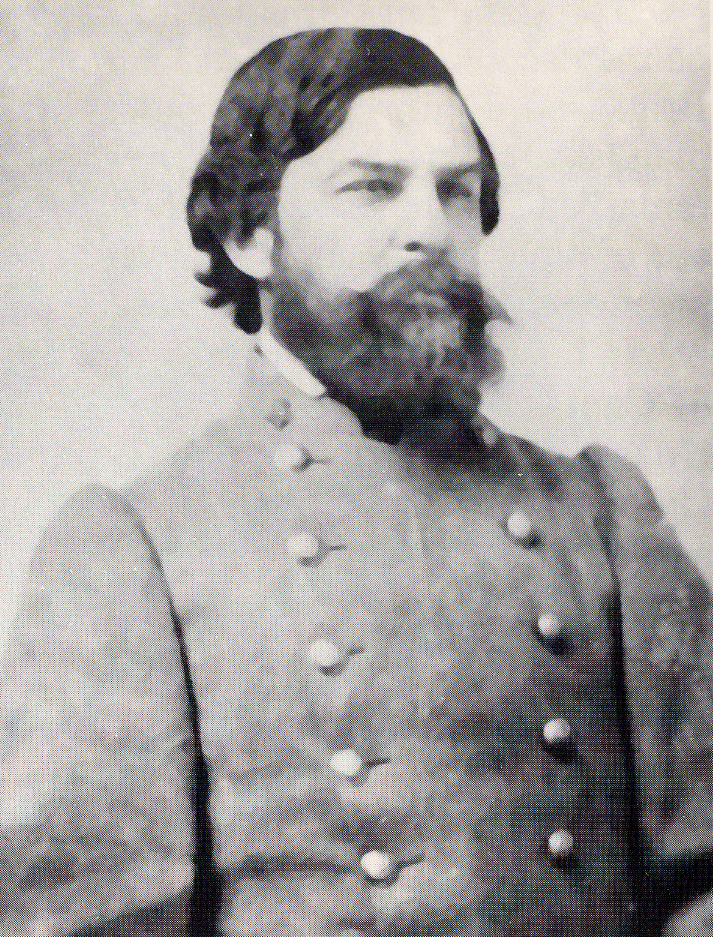

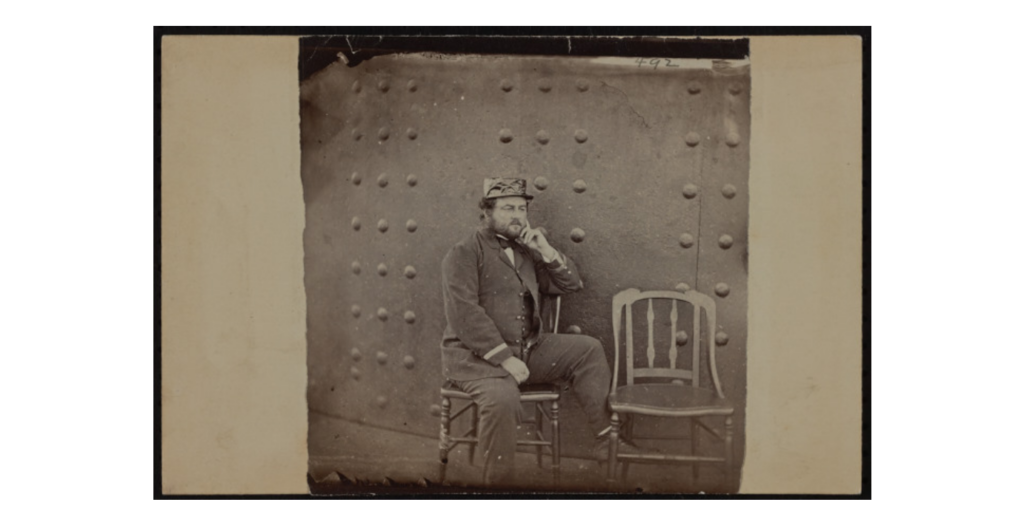

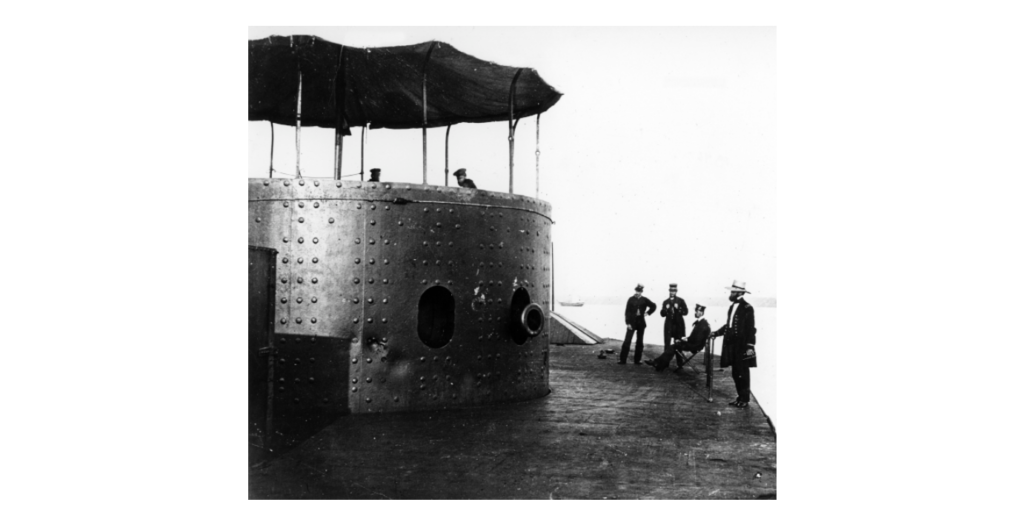

Following the Drewry’s Bluff fight, Lieutenant William Jeffers decided to write a detailed report to Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough regarding Monitor’s fighting abilities. The ironclad’s commander was considered an ordnance expert and was assigned to Monitor to survey the experimental ironclad’s strengths and weaknesses. Jeffers did not like the ship and was quite contemptuous of its design. His report to Goldsborough highlighted several significant problems:

- The captain could not control the ship from the pilothouse. The pilothouse should have been placed atop the turret.

- The turret should have a protective shield to allow riflemen to be deployed.

- The turret did not have a full range of fire due to the location of the pilothouse and air intakes. Jeffers thought the range of fire to be 200 degrees rather than 360 degrees.

- Only one gun could fire at a time. The port stoppers were too heavy to operate in combat. The gun commander had limited visibility. The only view outside the turret was by looking over the gun barrels. The ironclad had limited fire control.

- The gun ports did not allow for adequate elevation of the guns.

- Ventilation was intolerable. Jeffers recorded and reported on June 16, 1862, the following temperatures: Gallery – 164 degrees, Engine Room – 128 degrees, and Berth Deck – 120 degrees.

Jeffers summarized his report:

Notwithstanding the recent battle in Hampton Roads and the exploits of the plated gunboats in the Western rivers, I am of the opinion that protecting the guns and gunners does not, except in special cases, compensate for the greatly diminished quantity of of artillery, slow speed, and inferior accuracy of fire; and that for general purposes wooden ships, shell guns and forts, whether for offense or defenses, have not yet been superseded. [2]

John Ericsson responded to Jeffers’s report with fury. He felt that the US Navy did not understand how to operate his vessel and arrogantly answered each one of Jeffer’s complaints. Ericsson noted that the port stoppers were not to be opened and closed after each shot. The turret, he maintained, should merely be turned away from the enemy’s fire when reloading, as was done during the engagement with Virginia.

He agreed that the pilothouse placement should be atop the turret. Ericsson wrote that this was an obvious solution to fire control and communications. He admitted that he had considered doing this while Monitor was under construction. The command center was not moved because it would have delayed the completion of the ship for over a month. The inventor concluded that the “damage to the national course which might have resulted from the delay is beyond computation.” [3]

Even though Ericsson was correct about the turret’s operation and pilothouse location, he admitted that the poor ventilation system was a significant problem when he wrote First Assistant Engineer Issac Newton: “You have had a very severe trial and cannot imagine anything more monotonous and disagreeable than life onboard the Monitor at anchor in the James River in the hot season.” Fireman George Geer was well aware that Monitor “was not properly ventilated for men to live in it in hot weather; and I do not think she will go in another action until she has some alteration made, as the men would drop at the Guns before they fought half [an] hour.”[4]

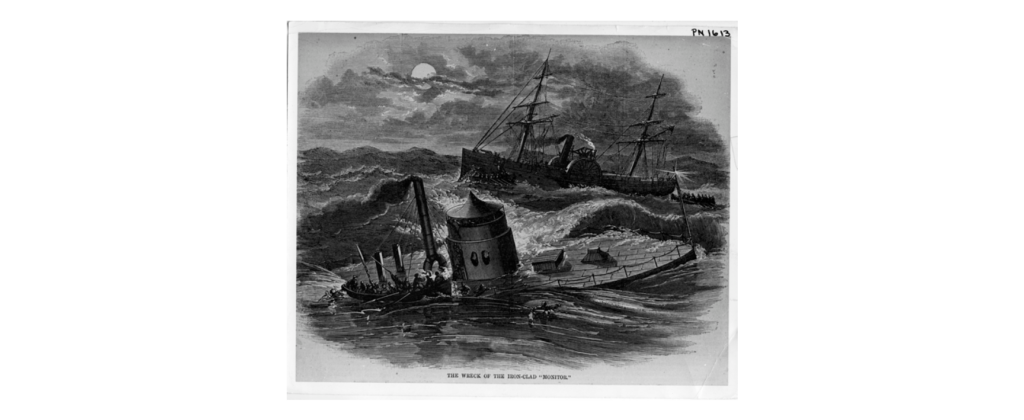

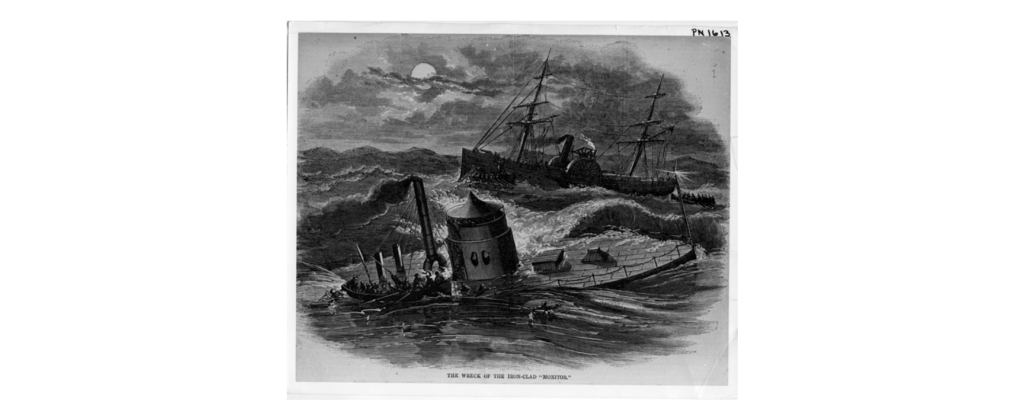

USS Monitor had received great acclaim after the Battle of Hampton Roads. Despite the ironclad’s impenetrability, numerous flaws become apparent during its first three months of service. Lt. John Lorimer Worden had discovered just how unseaworthy the ship was when the ironclad almost sank twice en route from New York to Hampton Roads. The hull design and connection to the overhanging deck caused Monitor to leak and lurch in heavy seas. Monitor was too slow, which lessened its steering qualities in strong seas and heavy currents. Even though the turret was shot-proof, it could only house two XI-inch Dahlgren shell guns. Consequently, the ironclad had limited firepower and field of field as well as poor fire control due to constricted vision caused by the placement of the pilothouse. [5]

The victory at Hampton Roads, public acclaim, and Ericsson’s sense of superiority duped naval leaders into believing that the monitor design was the wave of the future. Despite all of the noted obvious faults, the US Navy ordered 51 monitors during the war. Rear Admiral Samuel Francis DuPont, commander of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, lamented in 1863 to Assistant Secretary of the Navy G. V. Fox: “But, oh! The errors of details, which could have been corrected if these men of genius could have been induced to pay attention to the people who are to use their tests and inventions.” [6]

Monitors were modified in many ways after the Drewry’s Bluff fight. These improvements, nevertheless, did not solve critical problems. The monitor design was not the super weapon many thought it to be. Instead, it was the graft of politicians and the greed of shipbuilders who ignored the flaws and sought to profit off the war by the mass production of monitors.

- Lincoln to Welles, 10 March 1862, in The Valuable Papers of the Late Hon. Gideon Welles, Auction Catalog 1342, 24 January 1924, 8, no. 23, Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection, Allen County Public Library, Fort Wayne, IN.

- U. S. Department of the Navy, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, (Hereinafter cited as ORN), series 2, vol.18, p. 763.

- IBID, p. 737.

- William Marvel, ed., The Monitor Chronicles, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000, p. 72.

- John V. Quarstein and Robert L. Worden, From Ironclads to Admiral: John L. Worden and Naval Leadership, Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2025, p. 122.

- Gustavus Vasa Fox, Confidential Correspondence of Gustavus Vasa Fox, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, 1861-1865, 2 vols., edited by Robert Means Thompson and Richard Wainwright, Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1972, I: 195.

The post Drewry’s Bluff After Action Report appeared first on The Mariners' Museum and Park.

Gold Rush Saves Whales 4 Mar 2025, 7:36 pm

America’s lucrative whaling industry was based along the northeastern coast in the 18th and 19th centuries. While it was a dangerous occupation that required months or even years at sea, products derived from whales were in great demand. Whale oil was used to illuminate homes and streets as well as lighthouses and as a lubricant for machinery. [1] Whale “bone” was more flexible than our bones, and it was thought of as “the plastic of the 1800s.” [2] Whalebones were used in making women’s corsets, hats, and collar stays, among other things. Other uses included soaps, paint, and varnish.

The California Gold Rush

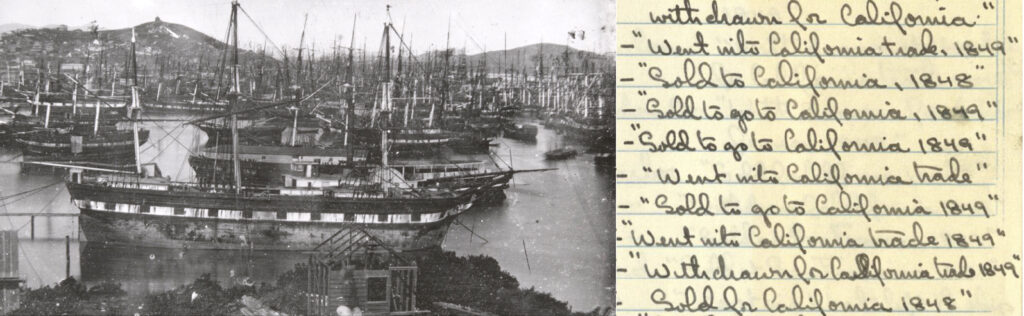

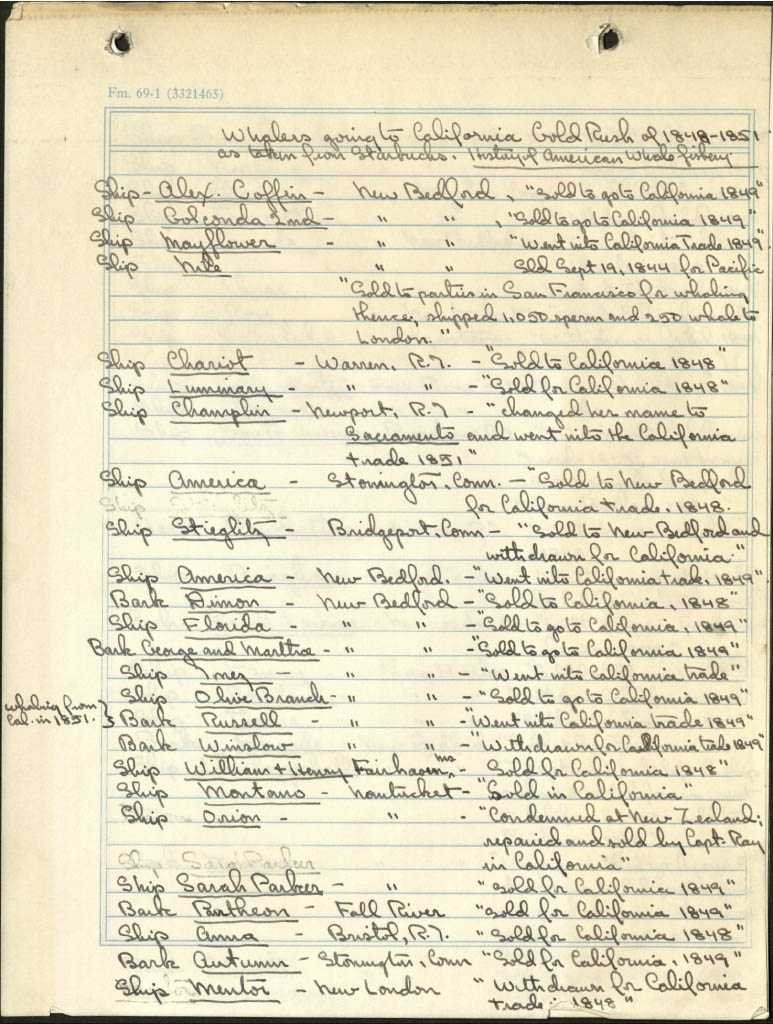

Many of us are familiar with the swift and radical changes brought on by the California Gold Rush in 1848. Connecting this event to the whaling industry would never have occurred to me had I not found research done by Albert M. Barnes, II, whose collection was donated to The Mariners’ Museum in 1986. Mr. Barnes created a list of 59 whaling vessels whose destiny was forever changed by the California Gold Rush.

Whalemen, like thousands of others, caught gold fever and rushed to California. The question was, how to get there? A choice had to be made as to the quickest route: over land, by sea, around the tip of South America, or by sea and land across Panama. In the winter of 1848-1849, the traditional route of migration to the Pacific — the great plains — was impassable due to rain-swollen rivers and mud. Mountain passes were blocked by snow and ice. [3]

This is a typical whaling ship in operation during the Gold Rush. Based in New Bedford, Massachusetts, Charles W. Morgan missed out on Gold Rush fever. She was chasing whales in the South Pacific from 1849 to 1853. [4]

According to historian Sandi Brewster-Walker, “whaling captains had the advantage of experience traveling the 18,000 nautical miles around Cape Hope to get to California.” [5] By December of 1849, most departing whaling vessels were laden with additional passengers, intent on mining gold.

Barnes’ list, titled “Whalers going to California Gold Rush of 1849-1851, as taken from Starbucks’ History of American Whale Fishing,” includes some hints at what was to become, such as “voyage broken up by crew deserting to California” and “sailed from Salem March 19, 1846 with company of 63; was hauled up on the bank at Sacramento and afterwards used as a prison.” Only a few returned to whaling a few years later.

Every Ship, Bark, Brig & schooner in Port are deserted by their crews. Some of them are regularly laid up and Captains & all have gone to the mines. Seamans wages are one hundred & twenty five dollars a month and we have to beg them to go at this price. It will cost a fortune to get a crew and we are obliged to make an agreement to bring them back or they will not Ship.

─Cleveland Forbes [6]

More than 700 ships ended up abandoned in San Francisco Bay. [7] These photographs, taken by William Shew and collected by Barnes, are from the winter of 1852-1853. The view shows San Francisco’s harbor with countless ships anchored. Also noted on the back of the images: “harbor is filled with rotting sailing vessels, crew having deserted to gold fields.”

Buried Ships in San Francisco Harbor

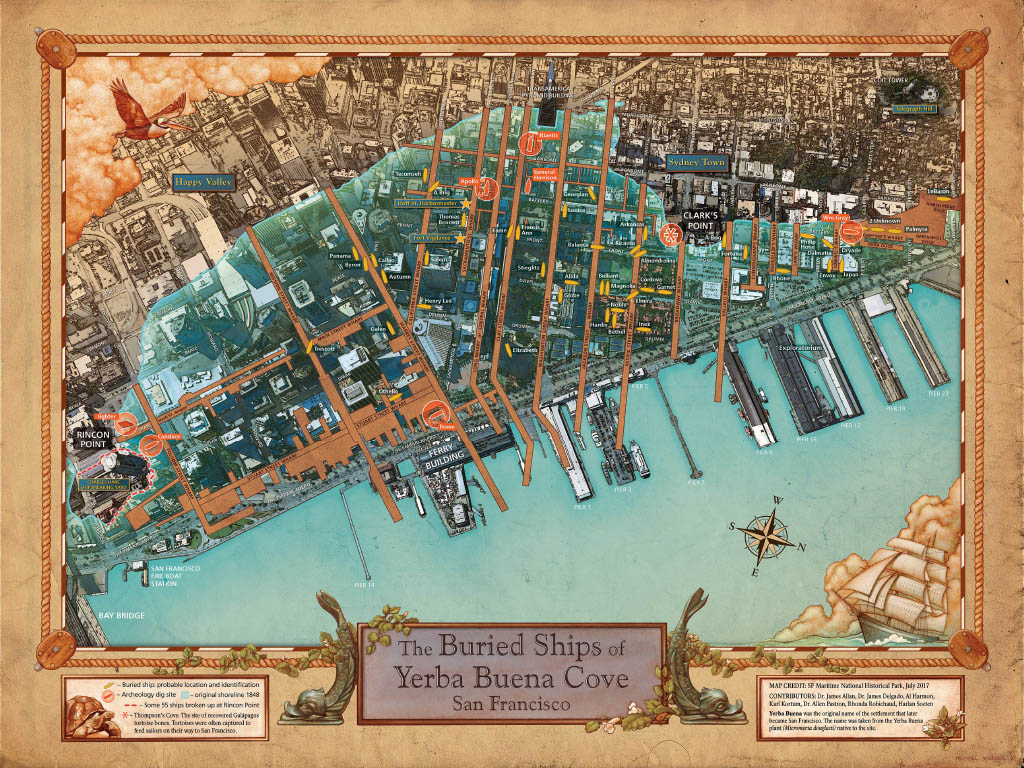

When I lived in San Francisco, I heard about new construction being halted due to archaeology. Thanks to the San Francisco Maritime Historical Society, I’ve learned more about these rotting ships. This map indicates the location of 47 ships that have been located and identified. The City’s shoreline in the 1850s and today is also outlined.

In 1849, San Francisco’s shoreline was called Yerba Buena Cove, “a shallow crescent-shaped bay with exposed tidal mudflats.” Most of the ships eventually sank in the mudflats, but a few were put to use as storeships, hotels or a prison. [7]

In conclusion, whales were saved as a result of gold fever, but only for a few years. The California Gold-Rush played a part in saving the whales, but it had more to do with timing. The chief factor in the decline of whale fishery was oil drilling and processing, initially into kerosene. (8) Today, whaling is prohibited by most countries around the world, and the North Pacific right whale and North Atlantic right whale are endangered species. Established in 1946, the International Whaling Commission works to conserve whales and monitors the regulation of whaling.

Sources:

1. Dolin, Eric Jay (2007). “Leviathan: The History of Whaling in America,” New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co.

2. McNamara, Robert. Accessed June 29, 2022, https://www.thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070

3. Delgado, James P. (1996). “To California by Sea: A Maritime History of the California Gold Rush,” Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

4. American Offshore Whaling Voyages: A Database, https://whalinghistory.org/av/, Mystic Seaport Museum, Inc. and New Bedford Whaling Museum.

5. Brewster-Walker, Sandi. Accessed December 14, 2024, https://www.massapequapost.com/articles/the-gold-rush-of-1849-whaling-captains-as-gold-miners/

6. Pomfret, John E. (1954). “California Gold Rush Voyages, 1848-1849: Three Original Narratives,” San Marino, CA: Huntington Library.

7. Olmsted, Nancy. “Gold Rush Ships Under San Francisco Streets.” Latitude 38, July 1987, https://www.latitude38.com/magazine/archive/

8. Purrington, Philip (1968). “Whale Fishery of New England,” New Bedford, MA: Reynolds-DeWalt Printing, Inc.

*Special thanks to Gina Bardi, Research Librarian at San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park Research Center

The post Gold Rush Saves Whales appeared first on The Mariners' Museum and Park.

The River, The Reverend, and The Revival 31 Jan 2025, 7:38 pm

The Mariners’ Museum and Park Collection is pretty vast! There are approximately 32,000 objects, equally divided between paintings, prints, ship models, and three-dimensional objects. Not to mention nearly 110,000 books, 800,000 photographs, films, and negatives, and over 1 million pieces of archival material in our library and archives.

Can you imagine how many different stories that can be researched and told?

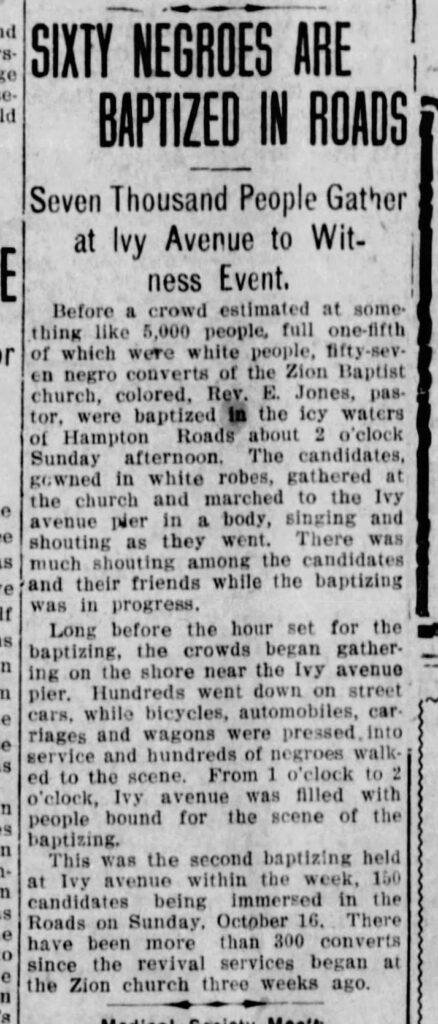

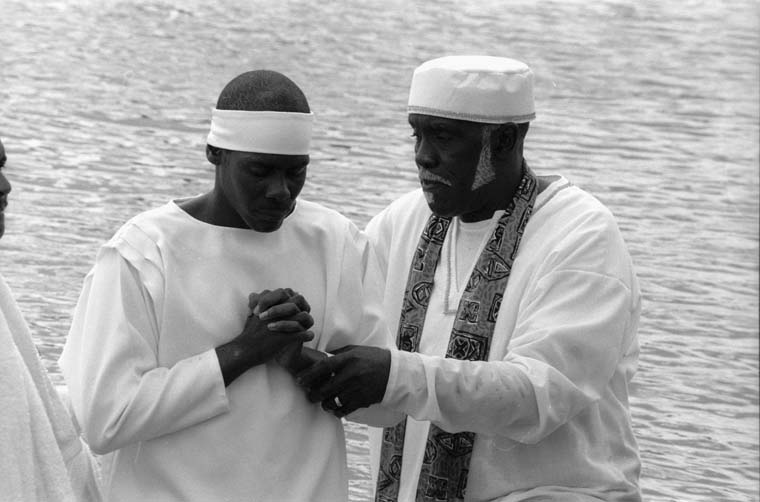

While searching through the Collection, Curator of Photography Sarah Puckitt came across a fascinating image of a baptism photo from 1914.

As we began our research, we looked at the photo to see what clues the photo gives to aid us in our research.

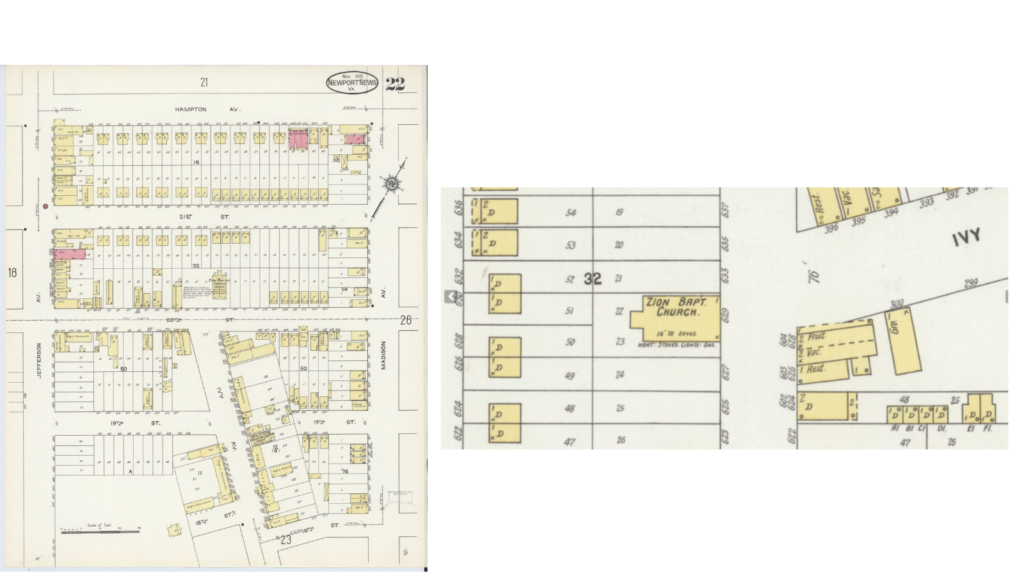

The photograph found in our Collection shows a baptism on November 8, 1914, along the James River in downtown Newport News, Virginia. Reverend Charles Edward Jones was pastor of Zion Baptist Church where he led the congregation for 39 years, beginning in 1902 until his untimely death in 1941. Zion Baptist Church was organized in 1896 under a cherry tree by a group of 13 like-minded individuals who had migrated to Newport News from other areas of Virginia and the Carolinas. During Rev. Jones’ leadership, Zion held worship services next to its current location at the intersection of 20th Street and Ivy Avenue in downtown Newport News, Virginia.

Finding an image of this baptism in the James River is amazing on many levels! To begin with, the image itself is very compelling. The central subject, people dressed in white waiting to be baptized, stands in front of a huge crowd on the shoreline. In the foreground waters, the event is framed by rowboats with men in them. All the people are dressed up, as if for church on Sunday.

Here’s another amazing thing about this photograph! Locals knew Elder Solomon Michaex of Gospel Spreading Church and The United House of Prayer had water baptisms. For many, baptisms during Easter were a community event. This image predates the establishment of both churches and is a jewel indeed.

The James River is known by locals as a major waterway in the Hampton Roads region for transportation, industry, recreation, and commerce. On the shores of the James, like many other rivers throughout the South, were common settings for baptisms up until the late 20th Century.

Baptisms were huge community events, drawing crowds of hundreds who gathered in boats and on the shore to witness this celebration of forgiveness and new life through the waters. According to a paper discovered at the Newsome House in Newport News and written by a former pastor of Zion Baptist Church, Reverend Jones would go into the bars, shot houses, and other places to bring people into a weekend revival, with the culmination being a Sunday baptism in the James River.

Based on several of the buildings that could be identified, some still-standing locations in the photograph are probably off the area known as Pinkett’s Beach in downtown Newport News.

Several department members had an opportunity to travel to the southeast area of Newport News to try and find the exact location where the photograph was taken. We found ourselves standing on a stretch of King-Lincoln Park, also known as Pinkett’s Beach in the downtown area.

While there, we met up with the current Senior Pastor of Zion Baptist Church, Reverend Dr. Tremayne M. Johnson. As we stood on the beach looking out to the water, one could visually recreate the action that took place there a little over 111 years ago. Rev. Dr. Johnson mentioned that baptism could likely be seen as an outward expression of inner grace with one’s self, your community, and beliefs.

Sadly, this is all we know about this historic image so far. However, the search continues for more!

Water has always been a part of African American history and culture. It has been symbolic in so many ways. The waters captured in the photo are the same waters in which hundreds found spiritual sustenance and renewed connection to their community. That very beach was a place of celebration. Celebration of new life, new beginnings, and a community brought together on and by the waters.

Water is and has been the gateway, connecting us to our heritage from the continent of Africa to where we are today. Water brings us life. It is a place to celebrate, to reflect, and to connect. Connecting, especially to our community, through our shared maritime heritage is what allows us to come together just like people did more than 100 years ago.

Sources:

- Zion Baptist Church. Accessed 1/22/2022, https://www.thezionbaptistchurch.com/about/our-story

- Dr. Susan Roach. Accessed on January 28, 2022, https://www.louisianafolklife.org/LT/Articles_Essays/creole_art_river_baptism.html

- Langston Hughes. Accessed February 17, 2022, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44428/the-negro-speaks-of-rivers#

- 1913 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, page 22. Courtesy The Martha Woodroof Hiden Memorial Virginiana Room at the Newport News Public Library, Newport News, Virginia.

- Daily Press 25 Oct 1910. (Newspapers.com). Accessed April 21, 2022.

The post The River, The Reverend, and The Revival appeared first on The Mariners' Museum and Park.

The Battle of Drewry’s Bluff 22 Jan 2025, 8:51 pm

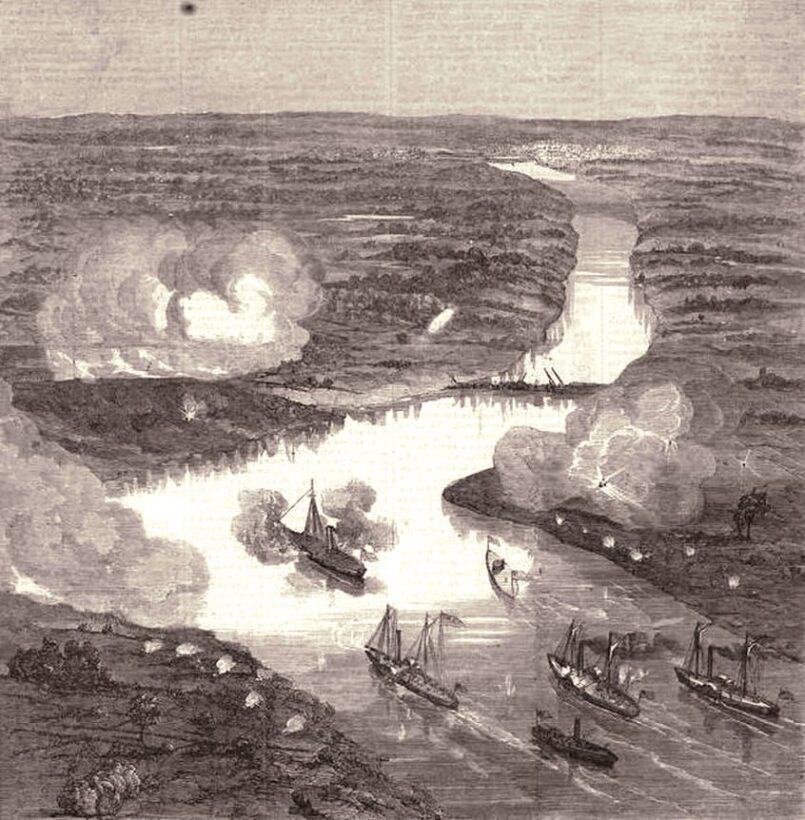

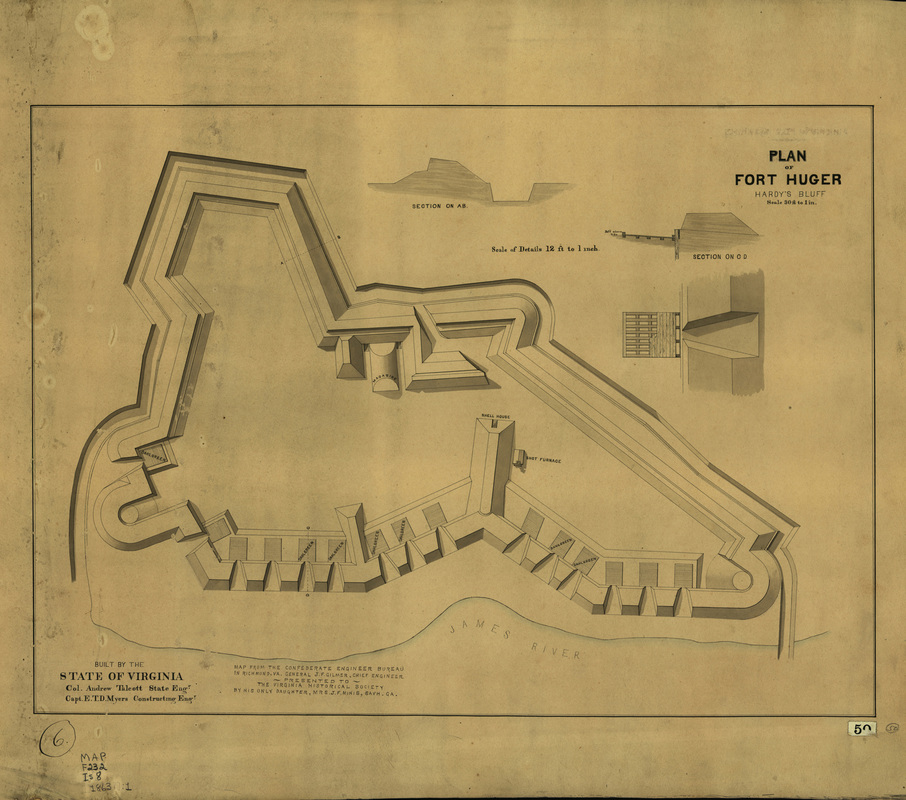

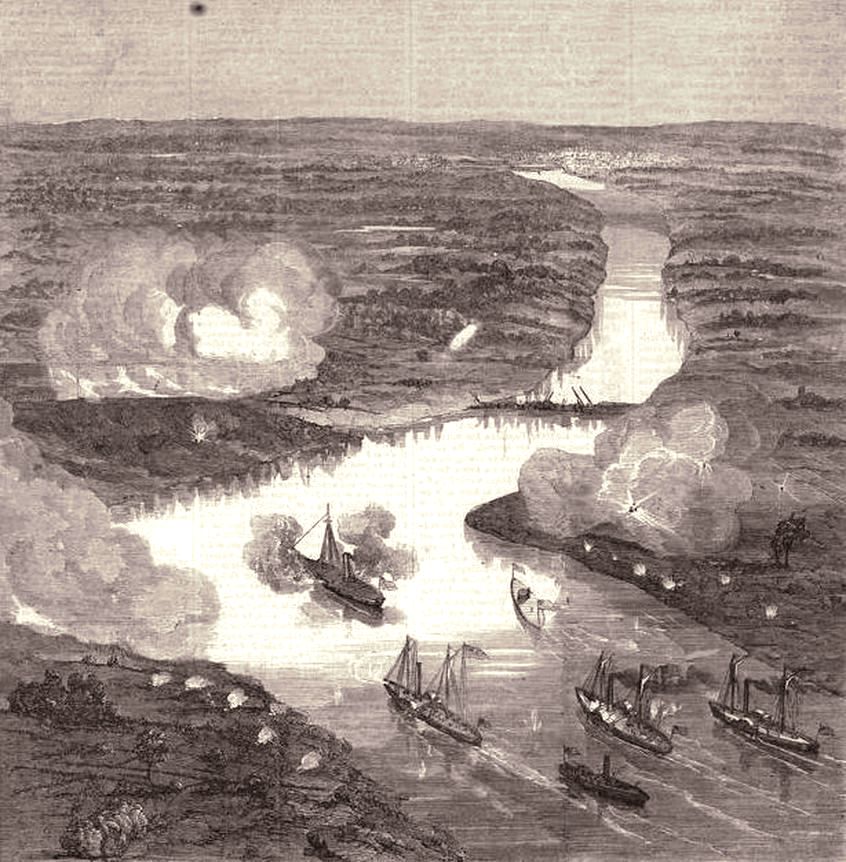

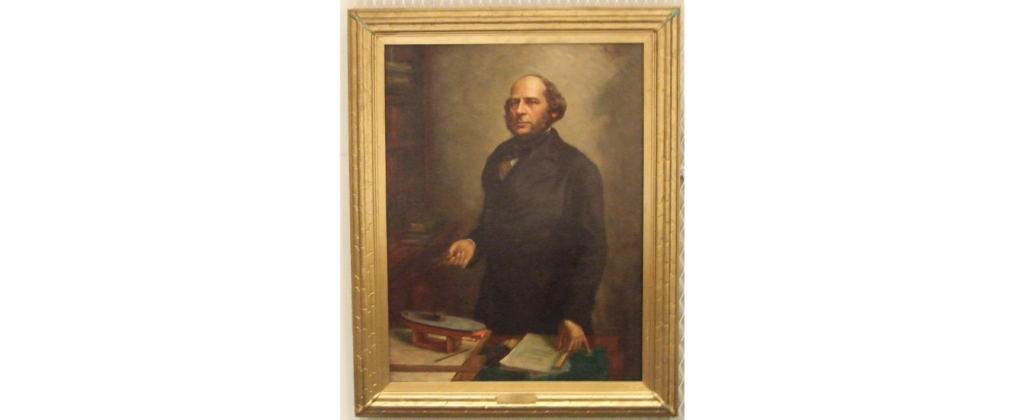

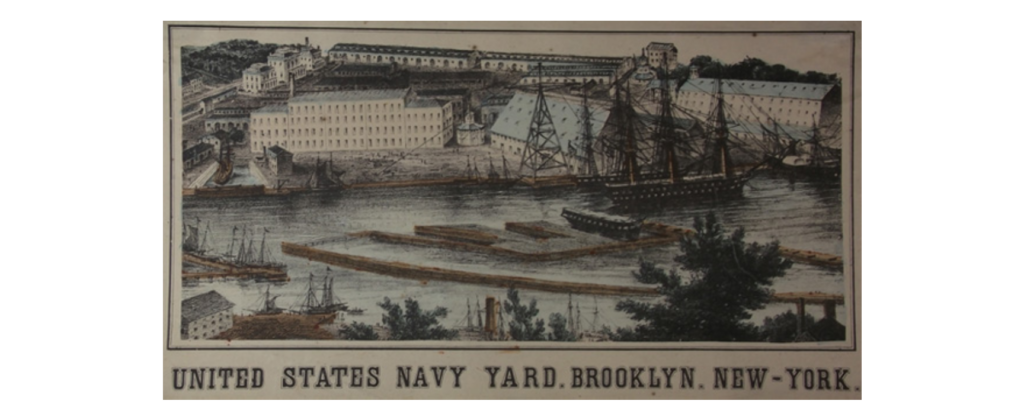

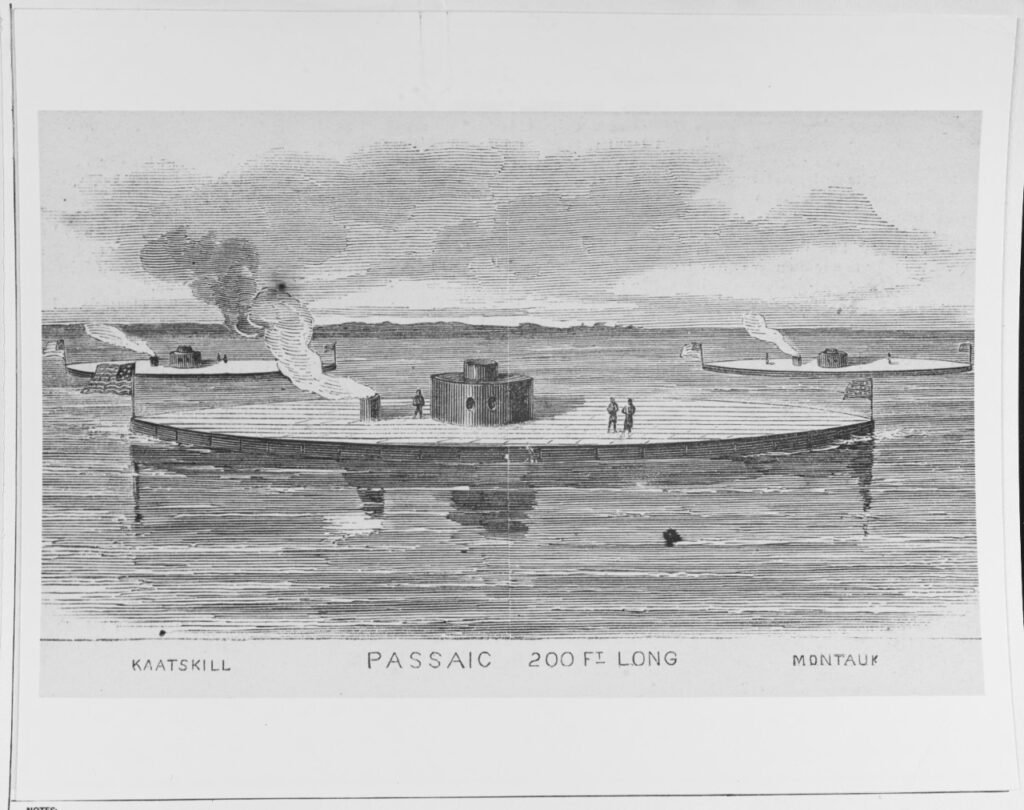

The destruction of CSS Virginia opened the James River pathway to Richmond. President Abraham Lincoln recognized that the Confederate capital was within the grasp of the Union Navy. He wanted to strike quickly into the heart of Confederate Virginia with the hopes that when Monitor and other Union ships attacked Sewells Point on May 8, 1862, USS Galena, captained by Commander John Rodgers, with several other ships, would engage and silence southside Confederate defenses, including Fort Boykins and Fort Huger. These forts were designed to fight wooden ships, not ironclads, and were abandoned. Richmond was only one day’s sail away, and once past Jamestown Island, there was nothing to stop the Union advance upriver.

The Union Flotilla

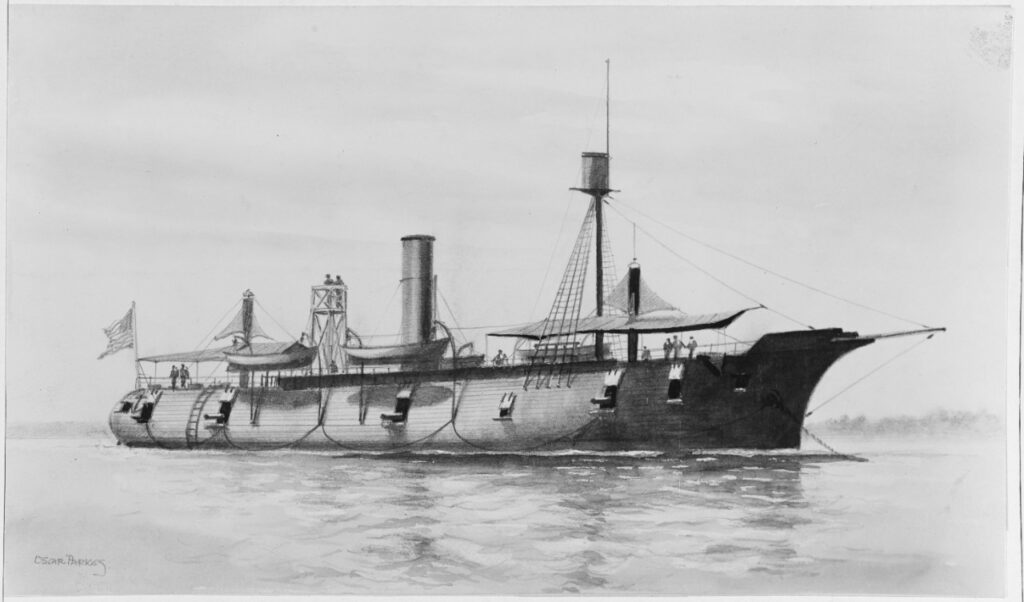

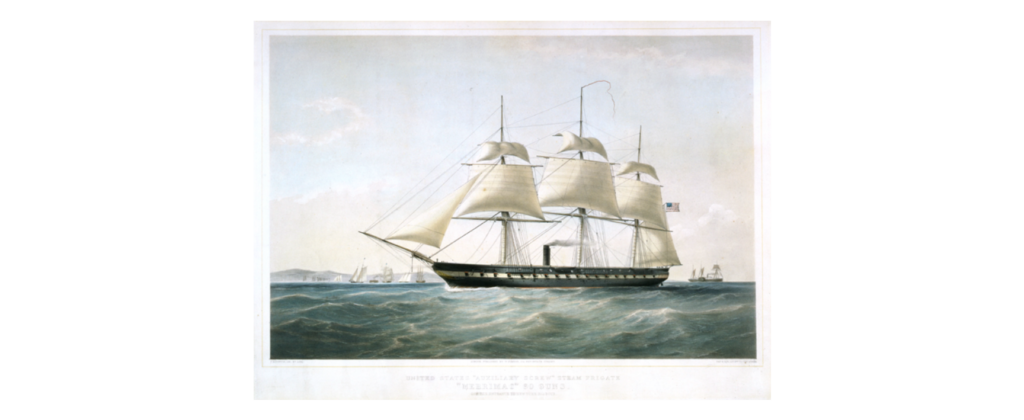

The flotilla was commanded by John Rodgers and would eventually include the ironclads USS Monitor, Galena, and Naugatuck. Galena was one of the three original ironclads and was poorly armored. This ironclad mounted six guns: two 100-pounder Parrott rifles and four XI-inch Dahlgren shell guns.

Naugatuck was an experimental ironclad originally conceived by Robert Stevens; however, technology changed before the ship neared completion. The Stevens family completed a smaller version in 1862; however, the US Navy refused to accept it, and Naugatuck joined the US Revenue Cutter Service.

The ironclad was armed with one 100-pounder Parrott. The wooden ships assigned to the expedition were the 90-day gunboat USS Port Royal and the side-wheel double-ender Aroostook.Port Royal was armed with one 100-pounder Parrott rifle, one X-inch Dahlgren shell gun, and six 24-pounder howitzers. The double-ender’s armament included one XI-inch Dahlgren, one 24-pounder Parrott rifle, and two 24-pounder howitzers. [1] Despite the rush to reach Richmond, the squadron had to stop and disarm every Confederate position below City Point. The Union ships reached the confluence of the James and Appomattox rivers by May 13.

Meanwhile, the Confederate capital was in an uproar over the approach of the Union fleet. The Confederate government began preparations to abandon the capital, and the city’s administration vowed to burn Richmond rather than see it fall into Union hands. Richmond’s lack of river defenses had been an issue for several months. Heretofore, the city had felt secure with Virginia serving as the river’s gatekeeper. Now that the ironclad was gone and the fortifications on the lower James powerless to stop the Federal ironclads, all appeared lost. General Robert E. Lee, however, was determined that Richmond “shall not be given up” and turned his attention to Drewry’s Bluff. He sent his son, Colonel George Washington Custis Lee, there to rush forward the earthwork construction.

Fortifying the Bluff

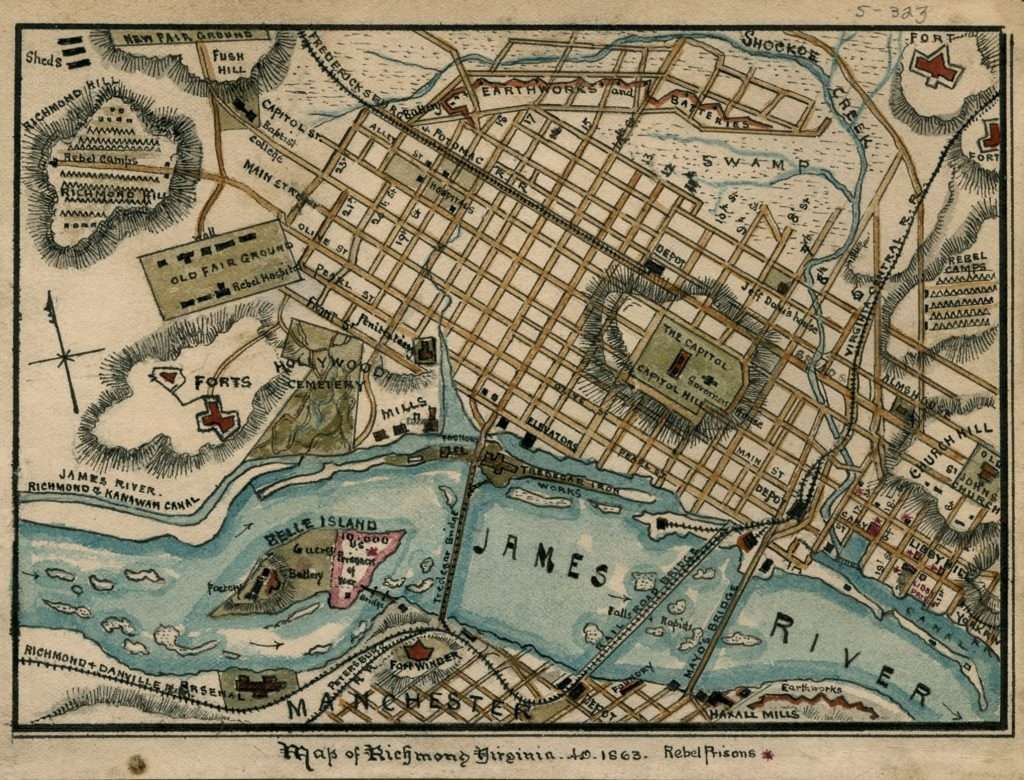

Drewry’s Bluff was a natural defensive position on the south side of the James River, located eight miles below Richmond. The bluff, rising almost 100 feet above the river, commanded a sharp bend in the river and was the last place to effectively mount a defense before reaching Richmond. Capt. Alfred L. Rives of the Confederate Engineers Bureau had surveyed the James River defenses in March 1862. Rives and fellow engineer Lt. Charles Mason studied the river with Capt. Augustus Hermann Drewry, commander of the Southside Heavy Artillery, to identify a suitable location to fortify and obstruct the river. Property owned by Drewry himself was selected. Lt. Mason designed the fort and Capt. Drewry’s command was assigned to build and defend it. As the earthwork known as Ft. Darling began to take shape, three heavy guns, two XIII-inch and one X-inch Columbiads, were placed in battery. Little had been accomplished when Commander John Randolph Tucker’s James River Squadron steamed upriver on May 9, 1862. When Tucker passed the bluff, he noticed the unpreparedness of the defenses. He immediately wrote to Commander Ebenezer Farrand, CSN, the recently appointed commander of Ft. Darling: “I feel very anxious for the fate of Richmond and would be happy to see you about the obstructive placed there–I think no time should be lost in making this point impassable.” [2]

Farrand was ordered to “lose not a moment in adopting and perfecting measures to prevent the enemy’s vessels from passing the river.”[3] Rodgers, investigating each rebel fort below City Point, gave the Confederates precious time to enhance their defenses. Reinforcements sent to the bluff included the Bedford Artillery, some infantry from Brig. Gen. William Mahone’s brigade, and the crew of CSS Virginia. Catesby Jones and his shipmates arrived at Drewry’s Bluff on the morning of May 13. He understood that “the enemy is in the river, and extraordinary exertions must be made to reply to him.” [4]

Jones organized his crew members into work parties, assisting Commander John Randolph Tucker’s sailors in constructing new gun emplacements. The men worked diligently, in the rain and mud, for the next two days. By the morning of May 15, the seamen had mounted several heavy guns taken from CSS Patrick Henry and Jamestown. Tucker’s men mounted a seven-inch rifle in an earth-covered log casemate located near the entrance to Fort Darling.

The Confederates made other arrangements to block the Union ship’s ability to pass the bluff. Jamestown was sunk, along with several other stone-laden vessels, like the schooner John W. Roach, approximately 300 yards in front of Fort Darling. This effectively closed the river to the federal vessels. Tucker held above the obstructions the remaining James River Squadron gunboats: CSS Patrick Henry, Teaser, and Beaufort. These ships were ready to engage any Union warship that might make its way past the defenses. Capt. John D. Simms and his detachment of Marines dug rifle pits below the bluff. Lt. John Taylor Wood deployed sailors as sharpshooters on the opposite bank of the river to harass the Union ships as they neared Drewry’s Bluff.

The Battle Begins

At about 6:30 am on May 15, Rodgers’s command got underway from its anchorage and steamed around the bend at Chaffin’s Bluff, with Rodgers in Galena taking the lead. The ironclad’s commander decided that Galena should be tested under fire.”I was convinced as soon as I came aboard that she would be riddled with shot,” Rodgers later wrote, “but the public thought differently, and I resolved to give the matter a fair trial.” [5] Galena had an experimental hull design, utilizing three overlapped one-inch plates for protection. The ironclad’s sides curved from the waterline to the top deck to give protection from opposing ships. However, this armor-clapboard design would provide inadequate protection against plunging shot, since the deck was built solely of wood.

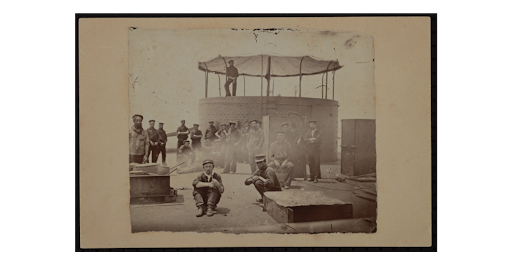

Despite these weaknesses, Galena headed the squadron followed by Monitor, Aroostook, Port Royal, and Naugatuck. As the flotilla passed Chaffin’s Bluff Confederate, riflemen began to pepper the Union warships. One sharpshooter picked off the leadsman on Galena. His replacement was also wounded. Assistant Paymaster William Keeler of Monitor noted that one ball “passed between my legs & another just over Lieutenant Greene’s head.”[6] Monitor’s crew stayed within their ironclad, despite the heat, throughout the engagement, while the wooden gunboats had to contend with the constant sniping, which they countered with their 24-pounders.

Rodgers maneuvered his ironclad into position 600 yards from the shore. The river was very narrow at this point, but Rodgers gracefully swung into action. Virginia’s former boatswain Charles H. Hasker was amazed by how Rodgers placed Galena into action with such “neatness and precision.” Hasker, who had previously served in the Royal Navy, called the maneuver “one of the most masterful pieces of seamanship of the whole war.” [7]

Rodgers knew that he must reduce the batteries on the bluff and then disperse with the rebel sharpshooters before he could open the door to Richmond through the obstructions. The federal fleet was immediately at a disadvantage. The obstructions blocked any opportunity to run past the batteries toward Richmond. Monitor was anchored astern of Galena. The other gunboats anchored about a half mile downriver off the mouth of Cornelius Creek. These vessels had to use their howitzers to contend with snipers as well as their heavy guns to shell the bluff. After 17 rounds, Naugatuck’s 100-pounder Parrott rifle burst. Thereafter the experimental ironclad could only shell the shoreline with its 24-pounders. Port Royal was also damaged during the fight as one shot crashed through the port bow of the gunboat and had to break off action for repairs. Once the gunboat came back into action, Port Royal was struck again by a heavy shot amidships causing minor damage. Nevertheless, the ship remained in action.

Galena was the primary target for the Confederate gunners. The ironclad had anchored “within point-blank range” of Fort Darling’s batteries, and the cannonade began to take effect. Ebenezer Farrand noted: “Nearly every one of our shots telling upon her iron surfaces.” [8] Seeing that Galena was being pounded by shot, Lt. William Jeffers moved Monitor virtually abreast of the larger ironclad in an effort to draw some of the Confederate shot away from Galena. Monitor’s new position and the dimensions of the turret’s gun ports did not allow the ironclad to elevate its two powerful XI-inch shell guns enough to hit the rebel gun positions. The Drewry’s Bluff cannoneers, knowing about Monitor’s shot-proof qualities, wasted little ammunition on the ironclad. “Three shot struck us,” Paymaster Keeler noted, “making deep indentations but doing us no real harm.”[9] Eventually, Monitor backed downstream and continued a deliberate fire from its final position.

Monitor’s crew was safe from the sharpshooter’s fire and shot from the batteries; however, “all suffered terribly for the want of fresh air. It was one of those warm, muggy days with a very rare atmosphere which, shut up closely like we were, made ventilation very difficult. At times we were filled with powder smoke below threatening suffocation to us all.”[10] The outside humidity, coupled with the heat from the engines, led Jeffers to estimate that it was 140 degrees within the turret. The hell-like qualities of a mixture of coal fumes, smoke, as well as powder smoke and sulfuric smells, made it unbearable within Monitor. Some of the men had to be taken out of the turret or engine room in order to breathe less infected air.

When the Union ships first steamed into sight on May 15, Farrand readied his command. As Galena maneuvered into position, the three guns in the main battery opened fire. Captain Drewry fired the first shot, which passed over the ironclad into the east side of the river. Even though the Confederates appeared to have the advantage with their defensive position atop the bluff and their use of plunging shot, they still encountered numerous problems. The X-inch Columbiad manned by the Bedford Artillery was loaded with a double charge of powder. Consequently, when the Columbiad was fired, it recoiled off its truck.

This heavy gun was not brought back into action until near the end of the engagement. Also, the recent heavy rains caused the casemate protecting the seven-inch Brooke gun to collapse, burying the sailors manning the gun after firing just a few shots. The crew dug themselves out and somehow was able to bring the Brooke gun back into action just before the battle concluded.

Commander Tucker commanded the five naval guns manned by sailors from CSS Virginia and Patrick Henry, while Catesby Jones was stationed at the Southside Artillery’s position to assist the volunteer artillerists in managing their guns. Jones was so exhausted by his efforts of the past five days that he actually dozed off on a shell box during the engagement. The naval battle, despite mounting very powerful ordnance, did not play as major a role as the seaman wished. Positioned to the left of the fort on the bluff’s brow, the sailors continued to bang away at the Union vessels throughout the battle and often needlessly exposed themselves to enemy fire.

Union cannon fire was rather effective early in the battle and inflicted 13 casualties. Several men were killed by fragments from a 100-pounder shell from Galena. Thomas Mann of the Southside Artillery remembered:

Shells from the Galena passed just over the crest of our parapets and

Exploded in our rear, scattering their fragments in every direction, together

With the sounds of the shells from the others, which flew wide of the mark,

Mingled with the roar of our guns, was the most startling, terrifying, diabolical

Sound which I had every heard or ever expected to hear again.[11]

“We could see large clouds of dirt & sand fly as shell after shell from our guns exploded in the rebel works,” Keeler remembered, “& no sooner was a gun silenced apparently in one portion of the batteries than they opened from some other part or from some new & heretofore unseen battery.” [12] One way the Confederates avoided casualties was that the men retreated into bomb proofs during periods of heavy Union shelling. When federal fire slackened, the defenders would rush back to their guns to return fire. This action also helped to conserve the Confederates’ limited ammunition supply. Despite the Union flotilla sending “their iron messengers with remarkable accuracy,” the “batteries on the Rebel side were beautifully served,” noted John Rodgers, “and put shot through our sides with great precision.”[13]

Galena Under Fire

As the duel between the batteries and warships continued through the morning, Farrand noticed he was running low on ammunition, so he let the Southside Heavy Artillery soldiers take a half-hour break. When the Confederate gunfire slackened, Rodgers thought his squadron was about to silence the Confederate guns; however, he also learned that Galena was running out of ammunition for its XI-inch Dahlgrens. Rodgers had to switch from explosive shells to solid shot, which had little effect on the rebel works. Farrand ordered Drewry’s men back to their Columbiads, and they reopened their cannonade of Galena with terrible effect. Every shot from the Confederate cannons seemed to strike the Union ironclad. Galena’s armor was broken, bent, and pierced in many places.

Despite the advantages of the Southerners’ position, some of the defenders, like Thomas Mann, thought that the federals “would finally overcome us.”[14] Nevertheless, the battle was decided in the Confederates’ favor with their heavy ordnance, constantly sending shot and shell into the Union vessels. They almost never missed their targets. Galena was struck by 43 projectiles. Its weak iron plating was penetrated thirteen times during the engagement. At about 11:05 a.m., the telling shot struck the ironclad. A shell from one of Patrick Henry’s guns, manned by former Virginia crew members, crashed through Galena’s bow and exploded. The shell ignited a cartridge, then being handled by a powder monkey, killing three men and wounding several others. The explosion sent “volumes of smoke,” according to Paymaster Keeler, “…issuing from the Galena’s ports & hatches & the cry went through us that she was on fire, or a shot had penetrated her boilers—her men poured out of her open ports on the side opposite the batteries, clinging to the anchor, to loose ropes…We at once raised our anchor to go to her assistance but found that she did not need it.”[15]

When the Confederates saw the smoke and flames rise from Galena, the gunners on the bluff “gave her three hearty cheers as she slipped her cables and moved downriver.” [16]

It appeared to the Confederates that Galena was retreating because of the explosion. Rodgers, who had barely escaped injury when the final shell exploded on his ironclad’s gun deck, had already decided to hoist the signal to break off action. Rodgers knew that his ship was running low on ammunition and had barely survived a damaging hail of Confederate fire. The entire squadron retreated down the river toward City Point. As he watched his enemy steam away from Drewry’s Bluff, Lt. John Taylor Wood, formerly of CSS Virginia, hailed Monitor’s pilothouse from the riverbank shouting, “Tell Captain Jeffers that is not the right way to Richmond.”[17]

Rodgers’s squadron endured “a perfect tempest of iron raining down and around us.” Galena suffered the greatest damage: its railings were shot away, the smokestack was riddled, and 24 crew members were listed as casualties. The battle demonstrated that the ironclad was “not shot-proof.” [18]

William Keeler of USS Monitor commented that Galena’s iron sides were pierced through and through by the heavy shot, apparently offering no more resistance than an eggshell,” verifying the opinion that “she was beneath naval criticism.” When the paymaster went aboard Galena, he thought that the ship:

Looked like a slaughterhouse..of human beings. Here was a body with the

hand, one arm & part of the breast torn off by a bursting shell–another

With the top of his head taken off the brains still steaming on the deck,

Partly across him lay one with both legs taken off at the hips & at

a little distance was another completely disembowel. The sides & ceiling

, overhead, the ropes & guns were spattered with blood & brains & lumps

of flesh while the decks were covered with large parts of half coagulated

Blood & strewn with portions of skulls, fragments of shells, arms, legs,

Hands, pieces of flesh & iron, splinters of wood & broken weapons were

Mixed in one confused, horrible mass. [19 ]

Rodgers knew that Drewry’s Bluff could be taken with a joint army-navy assault. Unfortunately, Major General George McClellan advised Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough that he had no troops to spare for such an attack. The federal navy was just eight miles from Richmond and would not reach that close to Richmond until April 1865.

A Win for the Confederates

The Battle of Drewry’s Bluff was a dramatic Confederate victory. Richmond was under immediate threat of being captured or at least shelled and destroyed by the Union flotilla. Yet, the cannoneers at Drewry’s Bluff had saved the capital. Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis had both ridden to Drewry’s Bluff when they heard the sound of heavy artillery. They arrived near the battle’s conclusion and “seemed well pleased with the results of the engagement.” [20] Commander Ebenezer Farrand was even more exuberant: “There is no doubt we struck them a hard blow.” Farrand concluded his battle report, stating, “The last was seen of them they were steaming down river.”

One Southern patriot celebrated the Union repulse with a short poem:

The Monitor was astonished,

And the Galena admonished,

And their efforts to ascend the stream

We’re mocked at.

While the dreaded Naugatuck

With the hardest kind of luck,

Was very nearly knocked

Into a cocked-hat.[21]

“The people of Richmond seemed to realize that we had saved the city from capture.” Midshipman Hardin Littlpage remembered, “and early in the after-noon wagon-loads of good things came down–cakes and pies, and confections of all sorts accompanied by a delegation of Richmond ladies.” [22] Midshipman William F. Clayton recalled, “Surely, from the quantity and quality, the markets must have been raked clean and the dear girls sat up all night cooking.” [23]

While the battle saved Richmond from capture by the US Navy, Keeler considered:

We do not regard the matter in the light of a defeat as we accomplished

Our purpose, which was to make a reconnaissance [sic}, ascertain the nature

& extent of the obstructions, the position & strength of the batteries. We

found them of such a nature that it was an impossibility to force them with

the means at our command & the river so narrow it is equally impossible

to bring a much larger force to bear. [24]

It was indeed a major Union defeat, as Fireman George Geer wrote his wife: “We have been fighting all day and have come off 2nd best.”[25]

Drewry’s Bluff remained the sole gatekeeping blocking the James River approach to the Confederate capital until the commissioning of the ironclad ram CSS Richmond. The days immediately before and after this May 15 engagement should have been utilized by the Union for a more concentrated Army-Navy assault on Richmond. Once past Drewry’s Bluff, Richmond would have surrendered and, perhaps, the war might have been over.

Endnotes

1. Paul Silverston,Civil War Navies 1854-1882, Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute press, 2001,

2.John M, Coski, Capital Navy: The Men, Ship’s, and Operations of the James River Squadron, Campbell, CA: Savas Woodbury Publishers, 1996, p.41

3. U.S, Department of the Navy, Official Records of the Union and Confederate in the War of the Rebellion, (hereinafter referred to as ORN), Washington, D.C.: U, S. Government Printing Office, 1894, Ser. 1, vol. 7, p. 636.

4. _____ Ser. 1, vol. 7, 799.

5. James Russell Soley, “The Navy in the Peninsular Campaign,” In Battle and Leaders of the Civil War, vol 2, edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, New York: Century Co., 1887, p.229-270

6. Robert W. Daley, How the Merrimac Won: The Strategic Story of the CSS Virginia, New York: Crowell Inc., 1957, p126’.

7, Soley, “The Navy in the Peninsular Campaign,” p.270.

8.ORN, ser. 1, vol.7,. 369.

9. Daley, Aboard the USS Monitor, p.126

10, IBID, p. 126.(

11. Samuel A. Mann, “New Light on the Great Drewry’s Bluff Fight,” SouthernHistorical Society Papers 34, p.92-93,

12. Daly, Aboard the USS Monitor, 128.

13. ORN, ser. I, vol. 7, p. 370.

14. Mann. “New Light on the Great Drewry’s Bluff Fight, p. 92.

15. Daly, Aboard the USS Monitor,” p. 128.

16. ORN, ser. 1, vol.7, 370.

17. Thomas J. Scharf, History of the Confederate States Navy from IT’S Organization to the Surrender of Its Last Vessel, New York: Rogers & Sherwood, 1887; reprint, New York; Grameray Books, Random House publishing, Inc., 1996, p.764.

18. ORN, I, 7, 357.

19. Daly, Aboard the USS Monitor, pp. 129-30.

20. Mann, “New Light on the Great Drewry’s Bluff Fight,’ p. 95.

21. IBID.

22. Hardin Beverly Littlepage, “With the Crew of the Virginia,” Civil War Times Illustrated (May 1974): p.42.

23. Coski, Capital Navy, p.47.

24. Daly, Aboard the USS Monitor, p.129.

25. Marvel, The Monitor Chronicles, p.72.

The post The Battle of Drewry’s Bluff appeared first on The Mariners' Museum and Park.

Little Mariners, Big Potential: Fostering Growth in Early Childhood Education 10 Jan 2025, 7:47 pm

One of the most repeated tenets around The Mariners’ is, “The school-aged child is the most important segment of our community.” This concept is core to our mission, and we’ve sought out many opportunities over the past several years to increase the number of students in our galleries. So when we learned there was a demand for more interactive learning experiences for local PreK students, we gladly dove in to help meet that need. In the fall of 2023, we added a new position to our team to lead program initiatives geared toward our youngest mariners: Early Childhood Educator.

Amanda Abrill stepped into the role and hit the ground running, leveraging her eight years of public school experience to inform our Early Childhood Education (ECE) strategy and launching new enrichment programs that have brought scores of PreK students onto The Mariners’ campus. Here’s an overview of how our ECE efforts are going and what we’ve learned so far from our intentional investment in early childhood programming.

Why Early Childhood?

According to data compiled by the Virginia Kindergarten Readiness Program, 40 percent of students entering kindergarten in Virginia are below benchmark standards in both reading and math. That means almost half of Virginia kindergartners begin grade school lacking the crucial academic skills they need to succeed. The Mariners’ is partnering with educators to help supplement in-class learning by designing programs specifically for Pre-K students.

Our goal is to provide our community’s Early Childhood Centers with free and meaningful enrichment experiences that are also engaging. We developed four new EEPs (Educational Enrichment Programs) that align with both the Virginia Department of Education’s Early Learning and Development Standards (ELDS) and the STREAMin3 curriculum, which combines interactive academic and social-emotional learning for children from birth to five years.

The Mariners’ had over 500 student engagements across seven ECE centers in 2024. Some of the programs occurred in person, and some were off-site.

Our 2024 early childhood programs included:

- Math at the Museum (in-house)

- Wild About Pollinators (in-house)

- What Floats Your Boat? (outreach)

- Our Five Senses (in-house)

These programs target PreK learning standards and are designed specifically for the classes that are visiting. 100 percent of students receive these valuable experiences at no cost.

Learning and Pivoting

In 2024, we learned a great deal about what works and what doesn’t, and we’re taking that information to heart as we strategize how to build on our early childhood accomplishments:

Transportation

Many ECE centers in the community do not have access to transportation. We’ve found that, although many educators are eager to take advantage of The Mariners’ ECE programs, these centers often don’t have vehicles or drivers that can get them to the Museum and back. Our two outreach programs, “What Floats Your Boat?” and “Our Five Senses” were developed with these centers in mind.

Age-based Learning

While it may not seem like there’s a significant difference between ages 3 and 4, the abilities and challenges between these two ages are vastly different. In an effort to ensure our programming is customized to the corresponding development level of the kids we serve, we’re considering ways to tweak our programs so that they’re slightly different between 3- and 4-year-olds to maximize effectiveness.

Redefining “Field Trip”

Here at The Mariners’, we are redefining what the term “field trip” means. Our approach involves multiple points of engagement over the course of a child’s academic career and provides high-quality enrichment experiences to multiple grade levels. This strategy now includes early childhood, which is often overlooked. An ECE center in our community can now book up to four PreK programs in one school year, giving young students multiple opportunities to feel a part of the Mariners’ community. However, many centers in our area are not yet used to this holistic approach. Our goal in 2025 is to get word out that The Mariners’ early childhood programs are here to stay, and creating meaningful partnerships with our community is our top priority.

Wonder Wednesdays

In the summer of 2024, The Mariners’ introduced Wonder Wednesdays, a free public program for kids ages two to four and their families/caregivers. For 10 weeks, the community flocked to the Bumblebee Learning Garden in Mariners’ Park for songs, games, and storytime centered around a different learning concept each week. The program was a huge success, serving about 450 guests in its inaugural year.

By making early childhood education a top priority, The Mariners’ is meeting kids where they are, helping them find their connection to the water from an early age. We hope this programming sets a firm foundation for young learners, encouraging them to become the next generation of mariners!

The post Little Mariners, Big Potential: Fostering Growth in Early Childhood Education appeared first on The Mariners' Museum and Park.

The Pontoon–Hydroplane Boat: A Motor Boat Built on Airplane Principles 30 Dec 2024, 6:21 pm

Is it a boat? Or an airplane? Perhaps both. Where would we be without those among us who put forth an improvement of an existing item or imagine something completely new? The creator of this vessel, Thomas Alva Edison Lake, was born into a family of inventors, and, having been named after the famous American inventor, his destiny seemed pre-set.

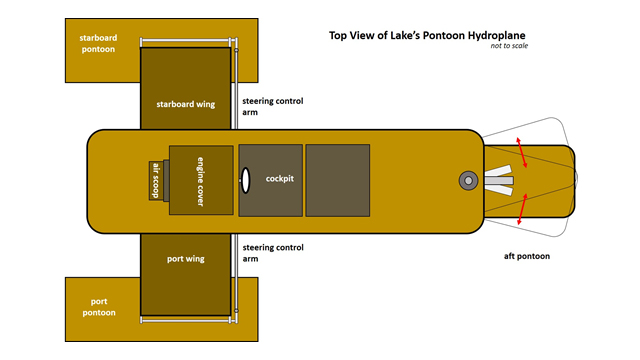

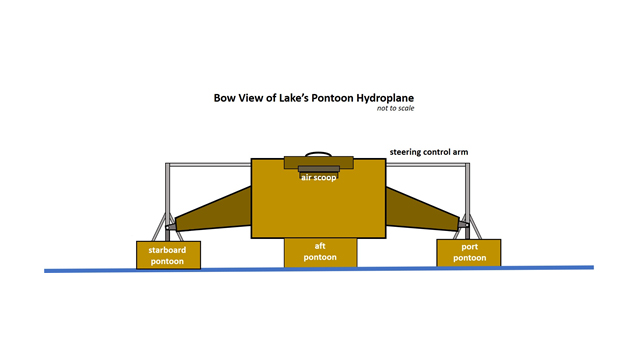

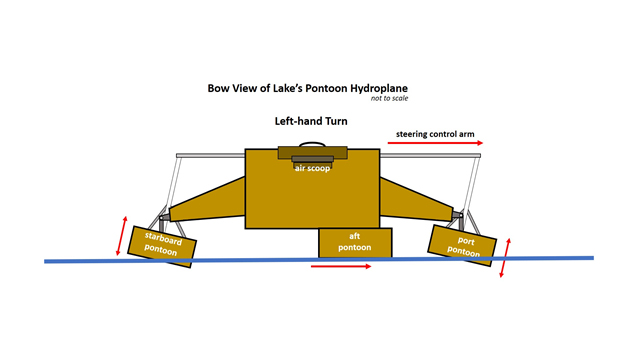

The year is 1932. Thomas Lake receives a patent for this experimental craft and on this day, he is about to test it in Milford, Connecticut. His patent application describes “a type of boat capable of skimming over the surface of the water at high speed and be able to make small radius turns at high speed without ‘skidding’ and maintain its stability at all times.” [1]

A clever combination of plane and watercraft, the boat is supported by a hydroplane float on each side, similar to the wings on an airplane. A third float sits at the rear of the craft and acts as a rudder. This three-point contact with the water allows for improved stability and maneuverability. The cushioning effect of the pontoons eliminates all shock, vibration or pounding due to rough water or when cutting across another boat’s wake.

Positioned in front of the driver’s seat is an Elto outboard motor “to exert a lifting as well as a forward propelling force. By tilting or ‘banking’ the forward set of pontoon-hydroplanes and steering with the rear one, turns can be made at high speed without ‘skidding’ or side-slipping.” [1] Extending through the bottom of the central body, the Elto’s propeller becomes the actual turning point of the whole craft, causing the rear of the craft to swing around the forward end. [2]

The photographs in this blog are part of the Robert G. Skerrett Collection. Skerrett was an engineer and prolific author of scientific papers and articles, including many for the Department of the Navy. The collection reveals his curiosity for a variety of subjects, including advancements in diving, salvage operations, and aeronautics. His personal photographs and sketches often illustrated his articles.

Skerrett was already acquainted with Thomas Edison Lake from articles he had previously written about Thomas’s father, Simon Lake, who is often credited as the inventor of the modern submarine. In 1932 Thomas Lake invited Skerrett to visit him in Connecticut and see his new invention, the pontoon-hydroplane boat. Correspondence between the two men indicates that Skerrett did pay Lake a visit and was impressed with the design, so much so that Skerrett offered to assist by publishing articles in New York newspapers. Lake was also seeking financial backing and hoped that his design would be of interest to the United States government, as well as commercial industry.

Check out this vintage newsreel footage of Thomas Lake testing out his invention.

Speed racing was becoming more and more popular in 1932. Designers Gar Wood and John Hacker were both pushing the speed record for boat racing that same year. However, their boats could not make sharp turns without skidding and capsizing. Had Lake’s craft been pitted against these boats, his would have won handily due to his vessel’s lack of wetted hull surface (creating less friction) and its ability to maintain speed in a tight turn. Lake filed several patents, including one for a “flying machine,” and another for what may have been the first automobile jack for changing a tire.

There is no record that Thomas Edison Lake’s pontoon-hydroplane boat went beyond the patent state. Such is the case with so many great ideas. Nevertheless, Lake’s concepts for increased stability and the ability to make turns at high speeds were realized in future racing boats.

Originally published in Sea History, Autumn 2023.

SOURCES

[1] Lake, Thomas A. Edison. 1932. Pontoon-Hydroplane Boat. US Patent 1,846,602, filed March 13, 1931, and issued February 23, 1932.

[2] New Haven Sunday Register, May 22, 1932.

The post The Pontoon–Hydroplane Boat: A Motor Boat Built on Airplane Principles appeared first on The Mariners' Museum and Park.

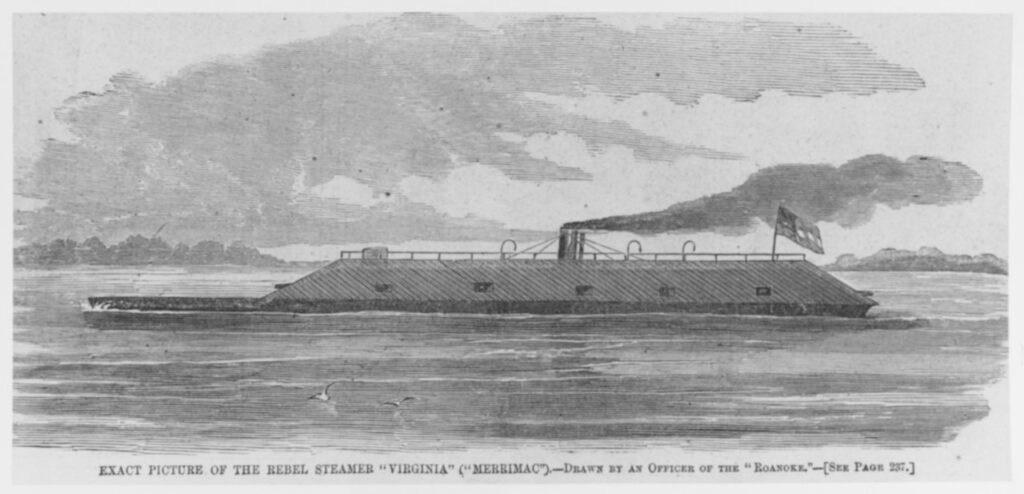

You Say Merrimack, I say Virginia 13 Dec 2024, 8:03 pm

The March 9, 1862 Battle of Hampton Roads. Similar to many other Civil War engagements, it has often been called numerous other frequently used titles. The Battle of the Ironclads and Monitor-Merrimac Battle are just two of the frequently used titles. This confusing nomenclature begs another question: What is the proper name of the Confederate ironclad? Is it Merrimac, Merrimack, or Virginia?

Monitor does not suffer from this type of identity crisis. The Union ironclad’s inventor, John Ericsson, was asked by the Assistant Secretary of the Navy to give the new ironclad, then referred to as “Ericsson’s Battery,” a proper name.

Since Ericsson believed that his innovative warship’s “impregnable and aggressive character…will admonish the leaders of the Southern Rebellion,” as well as prove to be a monitor to the Royal Navy’s ironclad frigate construction program, he proposed “to name the new battery Monitor.” The ironclad was such a success that “Monitor” became the name of an entire class and type of warship. [1]

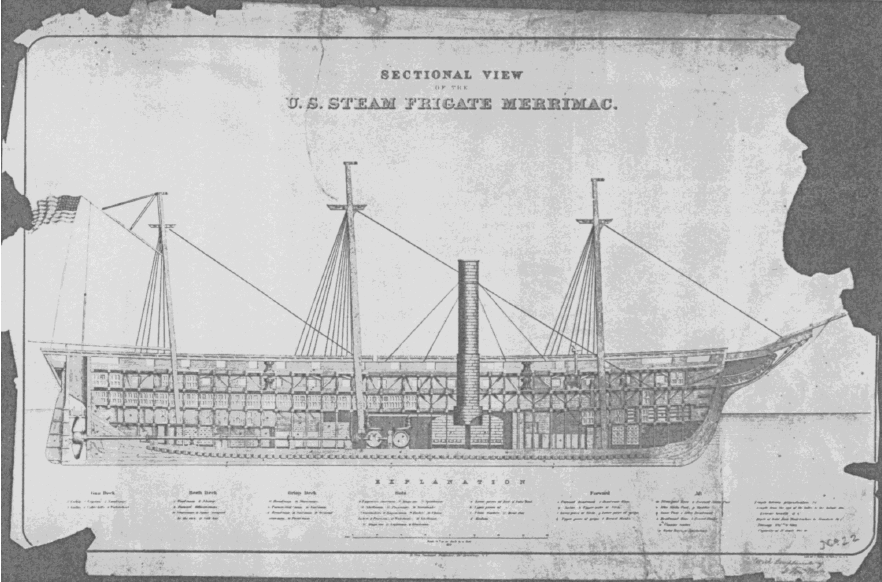

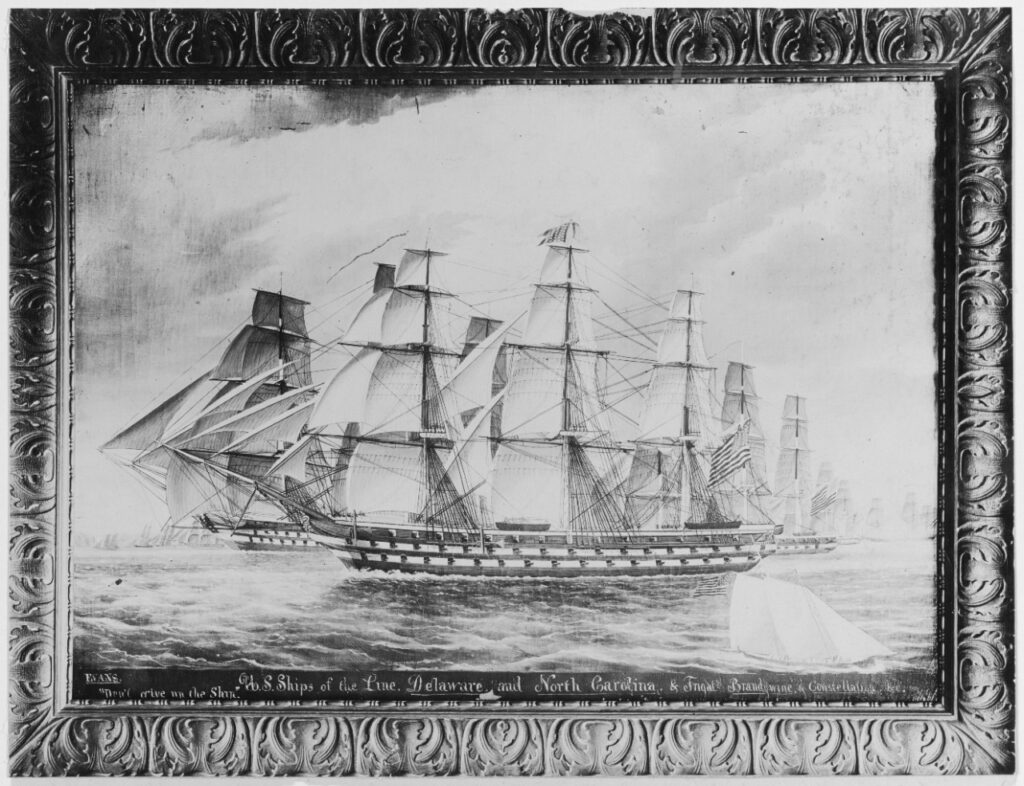

The Confederate ironclad’s name, however, is consistently inaccurate. The most common usage, used alike by Civil War participants and historians, is incorrect. The steam-powered, 40-gun frigate with a screw propeller built at Charlestown Navy Yard, Boston, was named USS Merrimack by John Lenthall, chief of the U.S. Bureau of Naval Construction, on September 25, 1854.

Naval Constructor E. H. Delano, who designed the frigate, noted the ship’s name as Merrimack on all of his plans for the frigate.[2] The warship was the first of a class of five frigates built during the 1850s. Each of the ships was named for an American river: Roanoke, Wabash, Colorado, Minnesota, and Merrimack.

This class of steam screw frigates was named Merrimack-class. President Franklin Pierce was a native of Concord, New Hampshire, the county seat of Merrimack County, located on the Merrimack River. He signed the act approving the appropriation and warship names on April 6, 1854. The frigate to be built at the Charlestown Navy Yard in Boston was spelled Merrimack. [3]

This evidence clearly documents that the frigate’s name should always be spelled with a “k” at the end of the word. Furthermore, the ship was named in honor of the Merrimack River, although confusion concerning the river’s spelling is commonplace. The first written reference to the river dates to 1691 in the grant by the joint regents of England, King William and Queen Mary, noting the northern boundary of Massachusetts as the Merrimack River.

Other references to the Merrimack spelling include Governor Thomas Hutchinson’s 1764 History of the Province of Massachusetts Bay. The name “Merrimack” is a Native American word said to mean “swift water.” By the mid-19th century, many writers, Henry David Thoreau excepted, had begun to drop the “k.” It appears that the spelling Merrimack is more often used at places along the river above Haverhill, New Hampshire. Haverhill is located at the head of navigation. Merrimac without the “k” is the popular spelling below Haverhill. The river formed the Merrimack Valley, which is also referred to as Merrimac Valley. This region was a major textile manufacturing area. One town in the valley is named Merrimac, but it was not established until 1876. This circumstance and the fact that it is easier to spell Merrimack with just a “c” rather than “k” is perhaps why so many Civil War contemporaries use the term Merrimac when writing about the frigate as well as the ironclad. [4] The Boston Evening Transcript on June 15, 1855, referred to the frigate as the Merrimac.

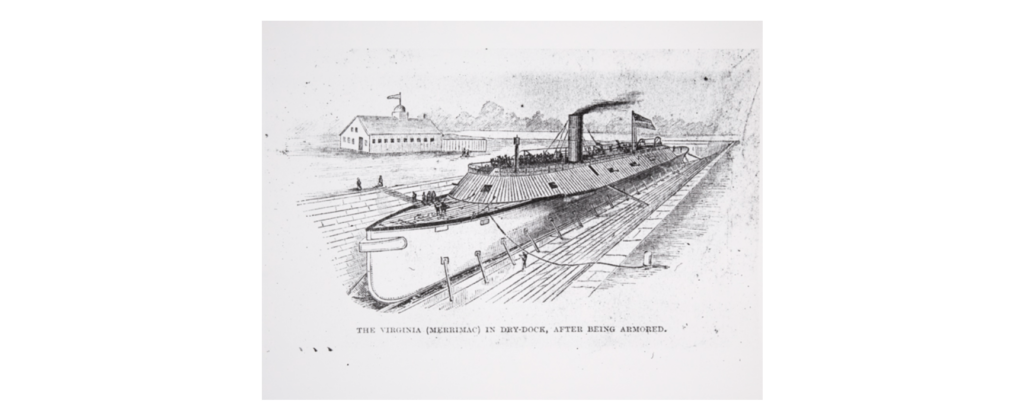

Once the Confederates raised the burnt hull of the frigate at Gosport Navy Yard, it was reconfigured into an ironclad and christened on February 17, 1862, as CSS Virginia. Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Russell Mallory and Flag Officer Franklin Buchanan, the ship’s commander, both refer to the ironclad after this date as Virginia.

Consequently, from February 1862, the ironclad should always be called Virginia. Unfortunately, not every Southerner recognized this technicality. Even the ironclad’s executive officer, Lieutenant Catesby ap Roger Jones, and chief engineer, H. Ashton Ramsay, often called the vessel Merrimac. Both of these men had served on the frigate prior to the war which may be the cause of their usage of both names in their wartime correspondence and post-war writings. The Southern newspapers usually refer to the vessel by its rechristened name, CSS Virginia; however Northern publications constantly used the name Merrimac without the “k.”

William Norris perhaps expressed the best summation clarifying the ironclad’s proper name when he wrote:

And Virginia was her name, not Merrimac, which has a nasal twang

equally abhorrent to sentiment and to melody, and meanly compares with

the sonorous sweetness of Virginia . She fought under Confederate colors,

And her fame belongs to all of use; but there was a peculiar fitness in the

we gave her. In Virginia, of Virginian iron and wood, and by Virginians

she was built, and in Virginia’s waters, now made classic by her exploits,

she made a record that shall live forever.[5]

The Confederate ironclad CSS Virginia will forevermore be indiscriminately called Merrimac, Merrimack, and Virginia. Accordingly, the battle, too, will be known by several different titles, but CSS Virginia should always be remembered as the vessel that proved once and for all the power of iron over wood.

Endnotes

- U.S. Department of the Navy, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of Rebellion, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1894, Ser. 1, vol. 2, p.148.

- John V. Quarstein, CSS Virginia: Sink Before Surrender, Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2012, pp.20-22.

- Paul H. Silverstone, Civil War Navies 1855-1883, Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2001, pp.15-17.

- Edward E. Barthell, Jr., The Mystery of the Merrimack, Muskegon, Michigan: Dana Printing Company, 1959, pp. 11-13.

- William Norris, The Story of the Confederate States’ Ship “Virginia’ (Once Merrimac): Her Victory Over the Monitor; Born March 7th, Died May 10th, 1862, Baltimore, MD: John B. Piet, 1879. Reprint, Southern Historical Society Papers 41 (September 1916), p. 234.

The post You Say Merrimack, I say Virginia appeared first on The Mariners' Museum and Park.

The Congress of Vienna and British Offshore Balancing Strategy 9 Dec 2024, 2:35 pm

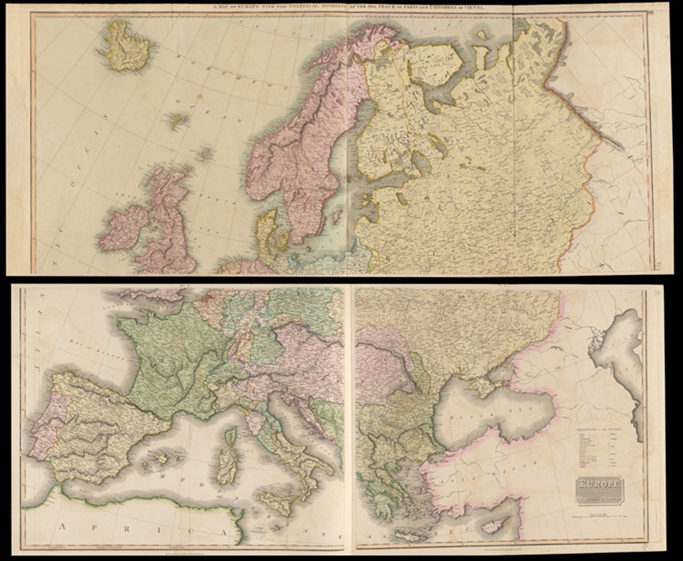

Should the US Grand Strategy continue its commitment to European security, or should it be focused elsewhere? Foreign policy and national security experts have debated that question since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. Foreign policy thinkers like Christopher Layne, John Mearsheimer, and Stephen Walt recently proposed a new US Grand Strategy based on Offshore balancing. Offshore balancing is a realist approach by which a great power retains its security and superpower position by using allied regional powers to balance against a potential competitor.1 In essence, this means that a global power has the capability to defend itself and extend its influence to support a coalition of regional powers against another global power. Scholars like Mearsheimer and Walt argue that the US is uniquely positioned to adopt offshore balancing as its national security strategy. They propose that the US should concentrate on maintaining its dominance in the Western Hemisphere while encouraging other nations to take the lead in containing emerging powers, intervening only when necessary.2 National security scholars point to 19th-century Great Britain as a model for what offshore balancing would look like.

This blog will highlight an 1815 Map of Europe to examine Great Britain’s grand offshore balancing strategy during the 19th century and will discuss:

- the international relations theories of Realism and its sub-theory of balance of power, explaining what each is and means;

- the Congress of Vienna and establishing the European balance of power;

- how the European balance of power from the Congress of Vienna settlement allowed Great Britain to implement its offshore balancing strategy; and

- if offshore balancing is possible in the 21st century.

The Theory of Realism and Balance of Power

Before discussing the Congress of Vienna, it’s essential to understand the theoretical framework by which International Relations scholars (and this blog) analyze it: Realism. Realism is the most dominant and oldest of the international relations theories. Realism says a country’s foreign policy should prioritize its national interests. Realists focus on competition between states and are generally uninterested in a state’s internal affairs.3

The basis of Realism is four assumptions about the international system:

- The international system is anarchic. In other words, no supreme power exists to resolve issues between nation-states.

- The nation-state is the principal actor in the international system.

- The nation-state is a singular, unitary actor.

- The decision-makers within the nation-states are rational actors who make decisions based on national interests.4

In essence, Realism is about self-preservation through the competition for power. Realism views international politics as a competition between nations, where each vies for power without any referee to regulate any nation’s actions. For those who want to read more about Realism, read articles and books by scholars Hans Morgenthau, John Mearsheimer, and Kenneth Waltz.

Within the theory of Realism is a concept called “balance of power.” The balance of power theory says peace is the outcome of preventing one state, faction, or figure from gaining enough power to dominate the others. If one state becomes too powerful, it will seek to take over its weaker neighbors, which leads its neighbors to unite in a defensive coalition. States can balance against each other through their internal policies by increasing their economic capabilities and military strength or developing clever strategies. States can also balance against each other externally by forming allies.5 To read more about the balance of power theory, read Kenneth Waltz’s Theory of International Politics.

The Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna was an 1815 conference created by and for the four allied powers of Russia, Austria, Great Britain, and Prussia to decide what Europe would look like in a post-Napoleonic War Europe. As the Napoleonic Wars ended, the four allied powers saw the need for a conference to (1) keep France from determining the fate of territories outside its borders, (2) improve their position through territory, and (3) determine the fate of lesser European powers.6 Additionally, the powers were concerned with two issues. The first issue was the ideas associated with the French Revolution. The second (and most important) issue was to prevent France (or any other European state) from starting a war as devastating as the Napoleonic Wars.7 The system the powers agreed was the best to stop another devastating war was the balance of power idea. The basis of the concept was that peace would be preserved if each of the five great powers (Russia, Austria, Great Britain, Prussia, and France) was militarily strong enough to defend against an attack of another power. The idea originated with British representative Viscount Castlereagh and Austrian representative Clemons von Metternich.8 From the negotiations before, during, and after the Congress of Vienna, Europe emerged with a balance of power system that resulted in relative peace until the outbreak of World War I.9

Congress of Vienna Settlements and European Balance of Power

The Congress of Vienna also established a territorial settlement agreement that created a balance of power system in Europe. This system was based on three zones: the West, Center, and East. Each zone consisted of territory that met the strategic needs of the powers, did not provoke jealousy from other powers, and did not antagonize France.10 The western zone consisted of numerous buffer states that aimed to prevent France from expanding beyond its borders. The center zone consisted of a power vacuum with a patchwork of German states ensuring Germany remained weak. In addition, the southern center zone also had a power vacuum of small states in which Austria could dominate within its sphere of influence. The most contentious part of the Congress of Vienna occurred during the Eastern Zone settlement negotiations. The settlement granted Russia most of Poland and Prussia half of Saxony.11

The territorial settlements of Austria, Prussia, and Russia mimicked each other because they divided the former European territories beyond France’s traditional borders amongst each of the mainland European great powers. All the great powers received territories except for Great Britain. Britain refused territory in continental Europe. The refusal of mainland European territory was by design. Britain wanted to remain free of European commitments and avoid being drawn into future continental wars or alliances. By not being drawn into any alliances, Britain was free to act or not act during any future European wars.12 Although Great Britain did not receive any territory on the European mainland, it did receive a favorable settlement from the Congress of Vienna. Britain negotiated for and ensured that an independent Belgian nation was established. Great Britain received territory in the form of colonies. The colonies were essential to Britain because they gave Britain a supplier of raw materials, a market for its goods, and naval bases for its ships protecting sea lanes. Additionally, Britain negotiated a favorable settlement about the rights to seas and rivers, including opening the Baltic Sea (formally controlled by Denmark) for access to the ports of Danzig and Riga.13

British Offshore Balancing

The Congress of Vienna settlement established a balance of power between the four great powers of mainland Europe. This balance created political conditions that allowed Great Britain, which had no territory on the European mainland, to implement its offshore balancing grand strategy. This strategy, coined “Splendid Isolation” by British statesman Lord Salisbury, was based on three main things: (1) geographical location, (2) control of the maritime domain, and (3) no near peer challenger.14

Geographical Location

As an island nation, Britain is separated from mainland Europe by the English Channel to the south (at its closest point, 21 miles separate Britain and mainland Europe), and the North Sea separates Britain from Norway to the east.15 Britain’s geographical separation from mainland Europe gave it a natural distance that no European power had experienced. The English Channel and North Sea act as natural protectors, making it difficult for land forces to invade the British Isle. Britain’s natural strategic Depth gives its homeland a defense few countries enjoy.

Strategic Depth refers to the distance between a state’s potential or actual enemies and its economic, political, and demographic heartland.16 This distance allows a defending state army more time to create defensive positions and opportunities to engage the invading state army at the time and place of the defending army’s choosing. It also causes the invading state army to travel longer distances, thus stretching logistical supply lines, which allows the defending state army to disrupt.17

Britain’s natural Strategic Depth from mainland Europe and its Navy gave the British Isles a well-defended homeland from potential invasions. The water is a natural protector, making it difficult for invading armies to traverse. The British Navy adds protection by engaging any possible land invasion force during transport to Britain’s borders. Additionally, strategic Depth allows Great Britain to establish defensive positions if its Navy cannot stop the landing force during transport.

Therefore, Britain’s Strategic Depth from mainland Europe (and not having any land from the Congress of Vienna settlement) separated it from the other four powers, allowing it to implement offshore balancing. Britain could observe what was happening on mainland Europe while keeping its distance and not getting involved unless one of the four powers had hegemonic desires. With an invasion unlikely, Britain could concentrate on its economic well-being and empire while sitting on the sidelines of Europe as a passive observer who participates when participation is advantageous for Britain.

Unrivaled Naval Superiority

During the 19th century, British interests revolved around protecting the homeland from invasion and imperial assets and projecting power beyond the English littoral waters. To accomplish this, the British government invested in its Navy. These investments enhanced Britain’s Naval capabilities, allowing it to enjoy unrivaled superiority amongst the other great European powers.18

One investment the British made to maintain a superior navy was its ship construction process. British warships were the strongest and had the longest service time due to construction improvements in traditional wooden ships. Older ships, especially ships of the line and frigates, were reinforced and strengthened with better-seasoned timber. The British built ships slowly in enclosed facilities protected from the weather, placing them on an improved overhaul schedule. With studier ships, the British could outfit the boat with larger guns, such as shell-firing guns, which offered greater explosive power per shot.19

Another investment the British made to maintain a superior navy was in the number of ships and sailors. In 1840, the British Navy had a battleship force of 77 ships, a difference of 54 battleships compared to France (23) and 44 battleships compared to Russia (33). By 1841, the British had 73 ships of the line afloat, 14 under construction, and five on order.20 The number of British ships increased because the British Parliament invested in expanding the number of sailors. In 1832, Parliament invested in 27,000 sailors and increased their investment to 43,000 in 1841.21

Arguably, the most important investment was in a new type of naval propulsion: steam. The British Navy pioneered steam propulsion, with eleven steam warships in service by 1835 and fifty-three in service by 1845.22 Steamships were vital in littoral operations. They could tow ships to their optimal position on the line, move inside the range of fixed guns designed to defend the coast against a ship with sails and carry out an offensive operation rather than a defensive operation waiting for a nation to attack.23

The investments in the British Navy allowed Britain to project power beyond the English Channel during the Crimean War in the Baltic Sea theatre. Sir Charles Napier, Commander-in-chief for the Baltic theatre, led a force of 18 ships with 1160 guns for a naval blockade around the Baltic Sea. This blockade kept five-eighths of the Russian naval strength and half of the Russian land forces tied up in the Baltic, unable to get to the Crimean theatre. Further, Napier’s naval forces destroyed the Bomarsund fortress and prevented Russia from establishing a naval base in the Aland islands.24

The Royal Navy’s supremacy gave Britain a protective feeling. They knew their Navy could defend the homeland and the empire because of robust ship construction, vast number of ships, and superior naval propulsion. These factors allowed the British Navy to deter any potential invader and serve as a balancer against any mainland European power-seeking hegemony.

Control of the Maritime Domain

The Congress of Vienna settlement left Europe with a balance of power system among the great European powers. However, the balance of power was among the four continental powers of France, Prussia, Austria, and Russia. On the sea, no one balanced Great Britain, who reigned supreme.

Britain gained control of the maritime domain (which, per NATO, “encompasses the oceans and seas-including everything on, above, and below the surface, in all direction”s) during the Napoleonic Wars.25 During the Napoleonic Wars, the British Navy defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Trafalgar. This battle thwarted Napoleon’s plans to invade the British Isles. With Napoleon’s defeat, the British Navy controlled the maritime domain.26

The British Empire derived its power and wealth from its colonial possessions in America and the Indian subcontinent, with India being the most important.27 The British relied on their Indian colony for the commodities it provided, such as cotton, silk, porcelain, spices, tea, and coffee. The commodities were then extracted in their raw form in India and shipped to Britain, where the raw commodity was made into a finished product. The finished product was then sent back to India, where it was sold or transited through India to places like China.28 With its colonies being the economic engine for the empire, Great Britain’s unrivaled control of the maritime domain allowed it to protect its colonies, making it difficult for a mainland European power to disrupt Britain’s economy.

In addition to being the economic engine for Great Britain, the strategic positioning of its colonies allowed the British Navy to project power. Many colonies Britain received through the Congress of Vienna settlement were strategically located islands and ports with good harbors. The strategic positions allowed the British Navy to protect the sea lanes, which the raw goods and finished products traversed to and from Great Britain. For example, the colony of Malta helped support the British Mediterranean fleet. With British control of Malta, Gibraltar, the Ionian Islands, and the Suez Canal, the Mediterranean was effectively a British lake.29 Because these colonies could be used as bases, the British could use the seas to facilitate their trade while blockading and denying another access to the sea trade routes.30

Can Offshore Balancing Work in the 21st Century?

Offshore balancing was a good idea for 19th-century Great Britain, but could it work in the 21st century? The answer is no. Implementing offshore balancing is a 19th-century answer to 21st-century problems. The main reason is that the 21st-century world is too integrated economically, politically, and militarily for a nation, especially a superpower, to implement offshore balancing.

Offshore balancing is based on selective restraint. While selective restraint was feasible for 19th-century Great Britain for reasons previously mentioned, the world’s interconnectedness economically, politically, and militarily creates limits that would make it difficult for a 21st-century nation to implement offshore balancing. Economically, nations are too integrated with each other’s economies, including nations with tense diplomatic relationships. Further, supply lines are such that goods manufactured in one nation depend on parts manufactured in another.

Politically, many nations are members of various supranational organizations. One of the keys to Great Britain implementing its offshore balancing strategy was staying out of alliances with mainland European powers. Not aligning with a mainland European power allowed Britain to pick and choose when and how it would become involved in a mainland European conflict. 21st-century nations are in a different situation than Great Britain. The nations are members of the United Nations and can partner with UN missions to keep the peace worldwide. In addition, the UN has five permanent members of the Security Council that can veto any United Nations resolution they object to.

Militarily, 21st-century nations have alliances with countries in North America, South America, Asia, Europe, and Africa. One example of a military alliance is the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). This alliance allows its member nations to respond to potential and actual conflicts. However, NATO membership does not give its member nations the same freedom Great Britain had to pick and choose its military involvements. If one NATO member is attacked, all NATO members are required to respond.

Conclusion

The Congress of Vienna settlement offered Great Britain an international climate to implement offshore balancing successfully. Britain’s geographical location, insulated economy, and unrivaled navy power that controlled the seas enabled Britain to adopt an isolationist grand strategy that prioritized its national interests and engaged with mainland European affairs only when Britain’s interests were threatened. Although political scientists advocate that this strategy can work today, the modern geopolitical environment makes implementing offshore balancing unfeasible. The integration of the world’s economies and the political and military alliances renders the isolationist principles of offshore balancing impractical. While learning about offshore balancing as a concept is needed, implementing it as a practical grand strategy in the 21st century is not advised nor encouraged.

End Notes

1. Major John Pendergrass, “Contemporary Lessons from British Offshore Balancing Strategy in the Napoleonic Wars,” Wild Blue Yonder Online Journal, Air University, December 7th, 2023. Access September 15, 2024. https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Wild-Blue-Yonder/Articles/Article-Display/Article/3607766/contemporary-lessons-from-british-offshore-balancing-strategy-in-the-napoleonic/

2. John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt, “The Case for Offshore Balancing: A Superior U.S. Grand Strategy,” Foreign Affairs 95, no. 4 (2016) pg. 71

3. “The A to Z of international relations,” The Economist, accessed September 5, 2024, https://www.economist.com/international-relations-a-to-z#R.

4. Sandra Antunes and Isabel Camisao “Introducing Realism in International Theory” in International Relations Theory, ed. Stephen McGlinchey, Christian Scheinpflug, and Rosie Walters (E-International Relations Publishing, 2017) pg. 15

e-ir.info/publication/international-relations-theory

5. “Los Dialogos Panamericanos: Balance of Power,” George Washington University, accessed September 22nd, 2024, blogs.gwu.edu/ccas-panamericanos/peace-studies-wiki/peace-studies-wiki/approaches-to-peace/balance-of-power/

6. Mark Jarrett, The Congress of Vienna and its Legacy: War and Great Power Diplomacy after Napoleon (London: I.B. Tauris & Company, limited 2013), Pg 69-70 ProQuest Ebook Central

7. Tim Chapman, The Congress of Vienna: Origins, Processes and Results (Taylor & Francis Group, 1998), pg. 1-2 ProQuest Ebook Central

8. Jarrett, The Congress of Vienna and its Legacy: War and Great Power Diplomacy after Napoleon. Pg 85-86

9. Tsira Shvandgiradze, “What was the Concert of Europe?” The Collector May 1, 2023. Thecollector.com/what-was-the-concert-of-europe/. Accessed September 30th, 2024. Chapman, The Congress of Vienna: Origins, Processes and Results pg. 33

10. Chapman, The Congress of Vienna: Origins, Processes and Results pg. 41-42

11. Ibid, 41-42

12. Ibid 20

13. Ibid, 50-52

14. Alexander Gale. “British Grand Strategy and the European Balance of Power: 1815-1914” The Collector June 2, 2024. Accessed September 30th, 2024. https://www.thecollector.com/british-grand-strategy-european-balance-power/