Or try one of the following: Afterdawn, Ajaxian, Andy Budd, Ask a Ninja, BBC News, BBC China, Brent Simmons, CNN, Digg, Flickr, Google News, Harvard Law, iTunes, Japanese Language, Newspond, OK/Cancel, OS News, Phil Ringnalda, reddit, Romanian Language, Ryan Parman, Technorati, Engadget, Web 2.0 Show, XKCD, Yahoo! News, Zeldman

Pacific Yachting

West Coast Power & Sail Magazine Since 1968Logs in the Water 27 Mar 2025, 4:35 pm

BC’s coastal forest industry harvests more than 565 million cubic feet (16 million cubic metres) of softwood annually, down from 20 million in 2013. Most of this material is shipped on the water, and most of it shipped in log booms. Lumber prices have declined and fewer trees cut down mean fewer logs lost. But lower prices mean salvors get less for their recovered logs and are less likely to round them up. The salvage business, which has always been tough, dangerous and spasmodic, is now almost entirely gone. Lost large cedars used to be worth good money but today it’s mostly softwood for pulping and chips. Despite many efforts to better organize it, salvors are usually single, independent operators working when they can and always at the mercy of the wood buyers in the large lumber companies. Today, it is a business run by people who love the water, usually have other sources of income or salvage because they have always done it. In other words, it is not a viable business that is worthy of investment and scaling up. So, barring some environmental lobbying force and action by the provincial government to force lumber companies to be responsible for their debris, the problem of logs on the water is not going away.

On a clear and calm sunny day, floating logs can usually be seen a mile away. No problem so long as the helmsman is constantly on the lookout. On a grey, wet day, with windshield misted over and a good chop, every wave can look like a log and every log can look like a wave. Constant and studied vigilance is essential and the person at the wheel has to be ready to change course in an instant. When visual conditions are difficult, it is always best to slow down to five knots or less. A boat travelling at 10 knots seeing a log 200 feet (60 metres) away has one second to avoid a hit, at five knots the skipper has two seconds to abruptly change course. It can make all the difference between a miss, a direct hit or a glancing blow.

So now what? Obviously first take the boat out of gear or let the sails fly and come to a stop. Immediately check all bilges for water ingress. Depending on the severity, ensure everyone is wearing a life jacket. Act as necessary to stem the flow of water, if required. Take note of your surroundings and any nearby threats. If there is no water ingress then put the engine back in gear and listen carefully to the rotation of the prop checking for vibration as you slowly increase speed. Even a minor vibration can cause wear to the shaft and bearings over time. Then check the steering for stiffness and effectiveness through a full rotation. If all is well, you have probably escaped unscathed. Proceed cautiously to port but when there, check everything again when you are calm and collected. If all is good, thank your lucky stars.

Tips to Avoid Collision

1. Look Out Make sure you have a clear view of the water ahead of you. In poor light, fog, or rain, reduce or eliminate all onboard illumination from screens and instruments. Clean the windshield. If your wheel is astern, post a lookout up at the dodger where a better view can be had in driving rain, or open the dodger for an even clearer sighting. Better yet, if you are desperate to maintain speed post a lookout at the bow—if you can find one! Either way, never take your eyes off the water.

In bright sun, the glare is intense coming from direct sunlight bouncing off the water and off anything white and reflective on the boat. This will reduce visual acuity and your ability to see logs. It is also damaging to your eyes. Wear polarizing sunglasses that both reduce the light by 90 percent and cut the glare. Cover white fibereglass in your line of sight with dark cloth.

If you think you have seen a log, you probably have. And if you have seen one, there are usually others around, so be particularly vigilant. If you spot a big deadhead, call it into the coast guard, they may flag it as a hazard.

2. Slow Down Reducing speed will give you more distance and time to avoid a log spotted at the last second. Equally important, it will reduce the impact force. This can mean the difference between a log rolling under your boat to hit the prop or steering gear, or being nosed to the side. Also, eliminate distractions from music and chatter that cut into your ability to concentrate.

3. Plan you Avoidance Tactic If sailing, it’s best to turn to windward which will slow you down and avoid a broach, which could happen if you sailed to leeward. Best not to sail wing on wing in difficult conditions if you want to avoid the chaos of a rapid avoidance maneuver. If motoring, plan a move that will take you away from traffic, shallow water, or obstructions. Don’t forget to take your autopilot off before hauling on the wheel or you won’t be turning as fast as you think.

If you are towing a dinghy remember it may not follow your dodging maneuver and may hit the log you just cleverly avoided.

Post Collision Checklist

A small hole in a boat can let an enormous amount of water into the hull in a short period of time, so as soon as it’s safe to do so you should:

- Make sure all guests have their lifejackets on.

- Search the lockers and bilges for water.

- If you find water locate the source as quickly as possible.

- Stop the leak or reduce the flow.

- Empty the boat of water using hand bailers, pumps and electric bilge pumps.

- If you can’t stop the flow or reduce it enough to safely get underway contact the coast guard.

- If all seems well and you get back underway recheck your lockers and bilges periodically until you are able to check your hull for damage.

The post Logs in the Water appeared first on Pacific Yachting.

Shoulder Season Adventure 23 Mar 2025, 4:30 pm

It started as a dream to combine sailing and snowboarding. I spent hours researching sailing/skiing expeditions in Norway but I just couldn’t justify spending the money to fly across the world when I have my own boat. Plus, British Columbia’s geography seems so similar to those Scandinavian fjords, so shouldn’t it be possible to combine the two activities here in our own backyard?

Maybe I was overconfident in my ability to pull this off, or perhaps just a little naive. Regardless, I couldn’t get this idea out of my head and soon this multi-sport concept consumed me. I found four other women to join me, all snowboarders and all just as crazy as me. We weren’t best friends and one I hadn’t even met before, but that changed quickly after being in close confinement for seven days together on my 35-foot sailboat—a 1976 Jason 35. We all brought different skills to the expedition, but ultimately, it was our love for snow that shaped our commonalities. Abby Cooper brought her expertise as snow-nerd and photographer, Gillian Andrewshenko enlightened us with her ability to speak the truth, Caley Vanular graced us with her calm demeanor, Kate Ediger brought her big heart, and then there was me, who somehow convinced four others to trust me to guide them up the winding fjords of British Columbia’s intricate coastline.

The northwest wind pushed us south wing-on-wing from Campbell River across the Strait of Georgia. Our end goal was Princess Louisa Inlet. The mission didn’t seem to matter the moment we saw the orca’s sleek dorsal fin cut through the water in front of us. I turned the engine off and we floated beside the pod, feeling honoured to share the water with such powerful creatures. After a leisurely sail, we eventually made it to our anchorage at Goliath Bay where I taught my green crewmember, Gill, how to lower the anchor. We holed up for the night and watched the sparkle of the stars above us and the phosphorescence below us.

Darkness surrounded us in all directions as we left in the morning to try and reach Malibu Rapids for slack tide at noon. The cloud cover slowly dissipated as we neared Princess Louisa. The sun’s strong rays hit us and we quickly shed layers; the Sechelt (shíshálh) Nation’s original name Suivoolot (sunny and warm), seemed like a more fitting name. Abby pulled out the binoculars and was analyzing the terrain for signs of recent avalanches. We switched Navionics over to topo mode so we could compare what we were seeing to where we were in Princess Royal Channel. The hundreds of feet under my keel felt comforting as we zig-zagged up the channel; the mountains seemed to grow taller. As we rounded each corner, we became increasingly distracted by the new peaks that revealed themselves, luring us in with their promise of sweet turns.

I nosed Spray into Malibu Rapids just before noon, the currents were minimal and the tide was high. We were almost at our destination and anxious to start planning the next stage of our adventure. I could see why Captain Vancouver bypassed this entrance when searching for the Northwest Passage; I started out cautiously. With growing confidence, I pushed the throttle forward to give myself more steerage as I approached the next corner. I glanced down at Navionics and noticed the chart was still in black and white topo mode, but did not want to take my eyes away from the entrance ahead of me to switch it back. Moments later the boat lurched in a way that I had only imagined in my nightmares. The sudden movement threw Kate to the deck and the others grabbed on to the nearest shroud beside them. Instantly, I realized my error and threw back the throttle, yet the rock didn’t seem to pity my naivete. Spray bounced over the mass three times before twisting to one side and freeing herself. I glanced at the chart again and made the decision to keep moving forward, as I was almost at the actual passage. I thought back to my decision on purchasing a boat with an encapsulated keel and knew that even if I never took Spray offshore, the extra cost was worth every penny. My steerage seemed fine and I quickly instructed my crew on how to check the bilge. As the depth reading under my keel grew, a wave of relief flooded over me.

We tied up at the dock at the head of Princess Louisa and I collapsed on the dock in need of a stiff drink. I inspected the hull with my GoPro and was satisfied to leave repairs for another day. It was only then that I was able to take a breath and look up. The surrounding snow-covered peaks reached into the sky as if born by the ocean’s depths. With our gear strewn all around us we packed our bags and switched gears to mountain mode. A deep growler let loose somewhere above us and we knew it was the mountains warning us of what they are capable of.

The skills that my crew lacked on board the boat, they made up for by their enthusiasm to learn and by their wealth of knowledge in the mountains. It was my turn to step back as captain and let the others lead. Abby charged forward and we followed eagerly. It didn’t take long to realize that the hardest part of this uphill climb was route finding through the downed trees and an ironically low snow line. Our splitboards (a snowboard that splits down the middle making two skis with skins for climbing and touring) were strapped to our loaded packs as we crawled under and over trees plugging our way up. The trail we were following is commonly known to cruisers as the Trappers Cabin trail. I had last been here when I was eight years old on my family’s 28-foot Tollycraft. I don’t remember much from that trip, but I recall making it to the cabin. Easy right? As we postholed through the slushy snow trying to find the next little piece of flagging tape that led us forward, things slowed down substantially. There was enough snow to make the trail slow and slippery, but not enough to put our splitboards on. We finally made it past the remnants of the cabin and the partially frozen waterfall that marked our one third distance. It was already 14:00 and we knew that we had to make a decision based on all the factors that were stacking up against us.

It’s not an easy conversation to have, but egos must be put aside and the safety of the group must be the top priority. It was later in the day than we were hoping, the snowline was lower than expected, and there were limited resources for help. I swallowed my pride and piped up, agreeing that this was not our time. After months of planning, was this really how we were going to leave it? It took us four hours to descend as we carried our 60-pound bags and snowboards back down to sea level. Acceptance slowly surged over the group as we all fought to keep our spirits high.

Spray welcomed our tired bodies home as the sun set over the pristine inlet. I lit the diesel stove and we piled back aboard. We slid our snowboards back into the hold and it didn’t take long before the group was playing a game of dice and starting to plan next year’s attempt.

So, maybe British Columbia’s coast isn’t exactly the same as Norway’s. But I’m still convinced our mission of combining snow and sail is possible. Perhaps it just takes a little more effort along the way to really earn those turns? I just hope that next year there are no rocks in the way.

The post Shoulder Season Adventure appeared first on Pacific Yachting.

Do you have expired marine flares? 12 Mar 2025, 4:21 pm

Flares manufactured in 2021 or earlier expire this year, as Transport Canada approves them for four years. They should be replaced every third or fourth boating season.

To dispose of expired flares, do not light them, throw them overboard, or add them to household garbage.

CanBoat / NautiSavoir volunteers and select CIL Dealers are hosting Safety Equipment Education and Flare Disposal Days (see below) to collect expired marine flares for neutralization and safe disposal.

Dates and locations are subject to change. Check the CanBoat.ca site before you attend an event or lookup additional collection dates.

2025 Dates

March 29 The Harbour Chandler

52 Esplanade, Nanaimo

April 4-5 Trotac Marine Ltd

370 Gorge Road East, Victoria

April 26 Steveston Marine and Hardware

1667 West 5th Ave, Vancouver

May 17 Bitter End Boaters Exchange

1044 Seamount Way, Gibsons

May 24 Lake’s Marine Supplies

5968 Trans-Canada Highway, Duncan

June 7 Alberni Industrial Marine Supply

3149 Kingsway Ave, Port Alberni

The post Do you have expired marine flares? appeared first on Pacific Yachting.

Sailing Back to Haida Gwaii 11 Mar 2025, 8:04 pm

During our 25 years of sailing in waters far away from the BC coast we always wondered how Haida Gwaii—and the Gwaii Haanas area in particular—might be changing. If we returned would we feel the same “magic” we so much enjoyed in years past? This past summer we had the opportunity to find out.

We first sailed among “The Misty Isles” in 1980. Then they were still named the Queen Charlotte Islands, affectionately referred to as “the Galapagos of the Pacific Northwest.” This was a wild, remote and challenging environment where boaters had to arrive prepared, both mentally and physically. One had to be self-sufficient, ready to cope with often harsh, rapidly changing conditions, and equipped to make repairs without assistance. It helped to have a positive attitude, to quickly adapt to the vagaries of weather, to consider inconveniences as adventures, to anticipate adversity and to embrace serendipity.

We—among others—pioneered sailboat-based eco-adventures in the area. While each summer season started and ended with an exploration of the mainland coast, the four or five months in between were spent in Haida Gwaii. During a dozen full seasons we gained an intimate understanding of the place. Our trips were eight to 10-day adventures either along the east coast between Sandspit and Cape St James, or through Skidegate Narrows and down the west coast. A few times we circumnavigated Graham Island. We engaged enthusiastic people to share their knowledge of nature or culture. In turn, these specialists attracted guests who were keen to learn and hungry for experiences in the wilderness.

In the early years we explored dozens of sites with huge midden mounds but scant cedar remains—as well as the more obvious villages like Skedans, Tanuu, and Ninstints—which showed the greatness that once was. Ninstints on SGgang Gwaay was then a restricted Class A Provincial Park (not yet a UN World Heritage site), and was a silent, haunting village with more poles and house remains than any of the others.

In the 1980s there were few visitors. At most we would see some commercial fishermen (both Haida and otherwise), and several residents at the abandoned whaling station of Rose Harbour. Among the Haida some individuals stood out for us. Wanagan was actively pushing for preservation and spent summers camped on SGgang Gwaay, Bill Reid was as passionate about stopping the destruction of the land as he was about art, and his young friend and student Guujaaw, was a carver, hunter, drummer and singer, who became an active voice for the Haida. Guujaaw was later elected President of the Haida Nation, and recently named Gidansda, hereditary chief of Skedans.

THE HAIDA HAVE always attributed their cultural uniqueness and strength to natural abundance in the seas and on the land, but large clear-cuts were rapidly transforming the unique old growth forests. Telunkwan Island, which had been devastated by logging, became the focus for an international campaign to protect the wilderness. John Broadhead of the Island’s Protection Society, Thom Henley, who ran the Rediscovery Program on Graham Island, Paul George of the Western Canada Wilderness Committee, and Guujaaw—along with an increasing number of Haida people—began to stand up to the big logging companies, and to a very complicit provincial government. CBC’s “The Nature of Things” did a feature called “Which Way Windy Bay” which helped to elevate South Moresby from a provincial concern to a national issue. Walking in old growth forests fuelled in visitors an overwhelming sense of urgency to stand with the environmentalists and the Haida in support of preservation. After seeing the extent of the clear-cuts many of our guests became actively involved in the politics of preservation. Later, the Haida organized blockades and protests, which included the arrests of several elders. This in turn brought federal government pressure on the province to end the logging. In 1988 Parks Canada entered into a partnership with the Haida to create the Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve and Haida Heritage Site.

The visitor today reaps the benefit of the efforts of many to preserve a special part of nature. That fight is well documented in: Ian Gill’s: All That We Say Is Ours, or Elizabeth May’s: Paradise Won, the Struggle for South Moresby.

By 1991 we were confident in the conservation of Gwaii Haanas, soon to be the first co-managed national park in Canada, and we set sail for distant shore. We continued to guide adventures using the same format in coastal environments around the world and many of our past guests joined us along the way. Haida Gwaii was inevitably part of our conversations.

The next 10 years went in a flash. We eventually sold our Ocean 71 Darwin Sound and bought a Dufour 45, which we also named Darwin Sound. Another 15 years flashed by and it was not until last year—after crossing the Atlantic once again—that we sold our Dufour and returned home, boat-less.

AFTER 26 YEARS—and thanks to friends who kindly loaned us their boat—we sailed back to Haida Gwaii last summer. Any time you re-visit a place there is some trepidation. We wondered if the islands would still be the magical place we loved and remembered. Would our experience be hampered by park restrictions, by too many other visitors, or perhaps by development? Sailing into Skidegate Inlet we were excited to see new poles had been raised in front of Skidegate village, and yet more on the beach in front of the museum, which had also changed to include multiple buildings plus a carving shed humming with activity. Skidegate now clearly illustrates the success of the Haida resurgence.

After provisioning, catching up with friends, and visiting the much-expanded museum (and art galleries too) we set sail from Sandspit to Skedans, south toward the wilderness we so fondly remembered. It wasn’t high season yet we saw no other boats during our sail that first day, and very few in the days to come. Even with growing popularity, a limited daily quota for park visitors serves to ensure the area will not feel crowded. We met more kayakers than sailors and saw only a couple of charter vessels.

MOST VISITORS TO Gwaii Haanas restrict their journey to the east coast, where myriad inlets and bays allow for relatively calm sea conditions and protection can be found in any weather. However, during a high-pressure system with steady northwest winds sailors can enjoy excellent blue water sailing along the west coast (in depths of 1000 to 2000 metres) and many secure anchorages. There are still very few navigation aides in the islands, but in our experience the paper charts are accurate. The same water hole off Darwin Sound still offers a good source of clean drinking water, but with an improved dock. The cumbersome Fisheries and Oceans mooring buoys are gone, but some sites now offer visitor buoys for short stays. A couple of National Parks cabins have been built, and old squatters’ huts have been removed. In the south, Rose Harbour has not changed much, and is still a bit of a social centre, offering simple accommodation and meals for visitors. SGgang Gwaay was busy, but Watchmen ensured our visit would be tranquil by limiting the number of visitors on shore at the same time.

During many of our shore walks we relied on our memories and instincts to guide us. Our hike up into the San Cristobal Mountains was just as tough and rewarding as ever, and still without established trails. The underlying policy is to make it possible for a person to feel that they are among the few to have walked there.

The old village sites felt just as powerful to us as before. The carved poles and cedar planks have aged as they continue to serve as nurse wood for new growth, but a strong sense of place remains. Ninstints is still haunting, as well an outstanding exemplar of Haida wealth. Haida Gwaii Watchmen now preside over half a dozen of the main sites. They are the next generation, picking up Haida language, learning songs and dances, proud to be Haida and sharing their stories. We found them to be welcoming and friendly, engaging and well informed.

THE FORESTS THANKFULLY remain untouched. For many this brings an awareness that they have never seen an intact old growth rainforest. Most visit Windy Bay on Lyell Island, where David Suzuki filmed “Which Way Windy Bay” in 1984. A longhouse was built in Windy Bay during the fight to stop logging on Lyell Island, and a pole was raised in 2013 to commemorate the cooperation and co-management of Gwaii Haanas. Once onshore, visitors are greeted by resident Watchmen, then take the same quiet walk through the open forest floor which we so enjoyed during the 1980s. The giant Sitka spruce, so large that it takes a dozen people arm in arm to surround it, is still standing, and admired. Windy Bay is just one of many old growth forests in Gwaii Haanas. You could anchor in Poole Inlet on Burnaby Island or in Bag Harbour or Carpenter Bay, and feel the magic of equally magnificent old growth.

If you heard about the 2012 earthquake that disrupted the flow of hot water at Hot Springs Island don’t be dismayed. The hot pools are in better shape than ever. Watchmen look after this site too, offering hot showers to aid in keeping the various rock pools clean.

WE USED TO explore Burnaby Narrows at low tide, the rich inter-tidal area Bill Reid called the world’s longest sushi bar. Thanks to Gwaii Haanas management, visitors must now float over at high tide, and can no longer compromise the organisms by walking on them, or by collecting them. There are restrictions on transiting the narrows too. These positive changes and others can hopefully protect the rich abundance in this unique ecosystem.

This year we saw cetaceans, including humpbacks, greys, orcas and large pods of Dall’s porpoises and Pacific white-sided dolphins—frequently.

HAIDA GWAII WAS was and is known for its huge sea bird colonies: Ancient murrelets, storm petrels, auklets, puffins, and shearwaters, are among the many species that come to nest on these off-shore islands. Seabirds too are threatened by over-harvesting too far up the food chain, and since many are ground nesters, by rats, and raccoons. Avid birdwatchers are advised to visit from March to June, during the nesting season.

A trip around Cape St James will bring the hardy yachts-person by the largest sea lion colony on our coast, and just possibly to the group of resident orca whales that feed on seals and sea lions. The boisterous waters around the cape support puffins, murres and other sea birds, and is a place where one can often see black footed albatross. After the rather rough ride we recommend a stop at the long sandy beach at Woodruff Bay, a place we used to call Hawaii Beach.

WITHOUT A DOUBT our re-discovery of Haida Gwaii was positive in every way, and reassuring. We could still wander freely among ancient cedars, listen to Raven calling, sit quietly on a mossy hummock below a carved cedar, clamber ashore on a deserted beach, and anchor alone surrounded by nature.

Culture, song and dance honour the old ways, and encourage fresh creativity among younger Haida. There is a renewed sense of pride in their communities. Our first journey to Haida Gwaii in 1980 inspired us, but also ignited some concern about how something might be lost through increased impact and exploitation. Now, over 35 years later, it still is a wild, remote and challenging environment. We are confident that with continued vigilance the magic and sense of wonder will endure.

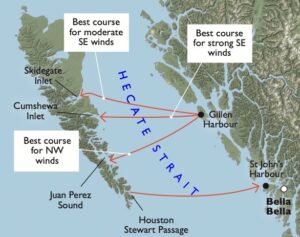

Hecate Strait is considered to be one of the most dangerous bodies of water in the world. The strait is relatively shallow, with reefs extending off much of the mainland coast, and Rose Spit is no place to have on your lee so wait for settled conditions before crossing. We prefer to sail across in moderate winds and we plan for a daylight passage. Although we have crossed between the northern tip of Vancouver Island and the southern tip of Haida Gwaii, we do not recommend this longer passage. We suggest the shorter distance between the mid-coast (north of Bella Bella) and the central part of Gwaii Haanas (Juan Perez Sound). Our favourite route is to cross from Gillen Harbour and return to St John’s Harbour. A return trip in strong northwest winds can be pure magic.

The Gwaii Haanas trip planner has a list of charter companies that can take you through the islands by sailboat, motor vessel or kayak.

The post Sailing Back to Haida Gwaii appeared first on Pacific Yachting.

TARPING GUIDE 11 Mar 2025, 7:43 pm

The environmental impact of bottom sanding and painting demands a careful approach to the task—and for good reason. Antifouling paints may contain elemental copper, cuprous oxide (a copper compound) or tinoxide compounds and some combine all three. They kill organisms attempting to attach to a painted surface. By design, most antifouling paints are toxic to marine life and can be absorbed by edible fish and shellfish. Toxins enter the environment through spillage, sanding, sand blasting or scraping. Residue on the ground or pavement can be transported into the water by stormwater runoff. And these toxicants can be passed up the food chain from mussels and worms to fish, birds and humans.

Under the Fisheries Act, releasing these wastes to fish-bearing waters is illegal. It states, “No person shall deposit or permit the deposit of a deleterious substance of any type in water frequented by fish or in any place under any conditions where the deleterious substance may enter any such water… and upon conviction in a court of law every person who contravenes this provision is guilty of a criminal offence. Maximum penalties are a fine up to $1 million or up to three years in prison, or both.” Yikes! Pretty serious stuff. Well worth the little bit of work that will keep you on the right side of the law and your conscience.

Starting at the bow, tape the 6 mil plastic to the hull to begin creating the skirt.

Starting at the bow, tape the 6 mil plastic to the hull to begin creating the skirt.

Staple the plastic to the wood stringers.

Staple the plastic to the wood stringers.

A doorway can be sealed closed by overlap the plastic and use nails to hold it together.

A doorway can be sealed closed by overlap the plastic and use nails to hold it together.The solution is simple. A tarp is put in place, under the cradle, before the boat is lowered into it. Then a sealed plastic skirt is taped onto the hull before sanding or grinding begins. This effectively contains all the toxic mess and allows for an easy and complete cleanup. Tarping will also prevent your grindings from blowing onto a neighbour’s boat—important for keeping the peace in an often-busy boatyard.

BEGIN BY PLACING, strong tarp on the ground where the cradle will be placed. Then, be sure to centre the cradle on the tarp before your boat is lowered into place. Use a big enough tarp to allow the skirt to remain within the confines of the ground tarp after you’ve made a tent of it.

You’ll need a sheet of six-mil plastic for the skirt and some tape to hold it to the hull. There are two schools of thought on which type of tape to use. Two-inch masking tape or duct tape.

Use weights to hold down the edges of the skirt.

Use weights to hold down the edges of the skirt.In duct tape’s favour is its strength. But, as anyone who’s used duct tape knows, it’s easy to apply, but difficult to get off. And once you do, there’s often glue residue left behind. As long as all the duct tape is removed within two to three days, glue residue shouldn’t be a huge problem, but if it is, you can easily clean it off with lacquer thinner.

Though masking tape is not as strong as duct tape, unless you leave it on the hull in the sun for three weeks, its easy to remove. If you’re expecting a monsoon, duct tape is the answer, but otherwise masking tape should do the trick.

Attaching the plastic skirt is definitely a two-person job, especially on a windy day.

Cut the plastic sheeting to size and begin taping at the bow of the boat. Be sure you’ve left the sheeting long enough; it should be able to reach the ground with enough slack to tent it out (so you’ll have enough room to work under the boat) and to allow you to weigh down the edges. Also be sure to have enough material so that you are able to overlap and seal the ends.

Once the plastic skirt is in position, place wood stringers—think of them as tent poles—inside the skirt that run from where you’ve taped the skirt onto the hull to the ground, leaving enough length to create a tent where you can easily work. Staple the plastic to the wood stringers from the outside. You’ll probably need to add a bit of additional support.

For a doorway you can overlap the plastic and use nails or pins to hold it together. By closing off the ends this way, you can easily open and re-close your tent.

Once everything is in place, use weights to hold down the edges of the skirt and get to work!

Don’t forget to wear protective clothing and a proper mask.

AT THE END of the exercise, when your boat has been lifted off the cradle, all you’ll need to do is carefully fold up the tarp and hand it off to whoever runs the boatyard for proper disposal. If you’re doing the work in your back yard, or in the driveway, take your mess to the recycling yard and they’ll (safely) deal with it.

TARPING TOOL BOX & TIPS

Ground Tarp

Be sure it’s large enough to allow you to “tent out” the plastic sheeting (to form the skirt) and that there’s enough extra width for weighting down the edges.

6-Mil Plastic Sheeting

Available in rolls.

Utility Knife

For cutting the plastic sheeting.

Nails

You’ll only need about a half dozen nails to pin the doorway at the bow.

Tape

Duct or masking tape for securing the tarps and sheeting.

A Proper Mask

You’re going to be sanding toxic bottom paint inside a sealed tent. Think about it—then go out and buy the best mask you can find. I recommend a respirator.

Protective Clothing

All around you is a swirling cloud of dust. You’ll need to do a lot better than an old T-shirt and ripped jeans. A full coverall is the only answer, and don’t forget a hat and safety glasses.

A Helper!

Preferably, a volunteer anxious to learn about boating. Promise a boat trip as soon as she’s back in the water. Beer and sandwiches always help. Popcorn and prizes. Anything!

The post TARPING GUIDE appeared first on Pacific Yachting.

The Graham Clarke Group Has Acquired the Oak Bay Marine Group’s Four Marinas 19 Feb 2025, 10:27 pm

Vancouverite Graham Clarke, 81, grew up Oak Bay and says he’s always hankered to return to his roots. He has now achieved that desire by buying the Oak Bay Marine Group (OBMG), thevenerable marine and hospitality company founded by Bob Wright 62 years ago. Wright was an ardent sport fisherman who wished to introduce boaters to the beauties of the BC coast while also catching fish. He began fulfilling his wish by building the Oak Bay Marina for pleasure craft on Turkey Point. Over the years, the company added sportfishing resorts and tourism and bought floating fishing lodges and three hotels, which have since been sold. Wright died in 2013 at age 82.

Graham Clarke with Brook Castelsky. Photo courtesy: Oak Bay Marine Group

Graham Clarke with Brook Castelsky. Photo courtesy: Oak Bay Marine GroupThe Graham Clarke Group’s recent purchase of OBMG’s properties includes not only Oak BayMarina, but also three other Vancouver Island marinas: Pedder Bay, North Saanich and Ladysmith. OBMG’s boathouse building company, the Marina Dockside Eatery, the Cape Santa Maria Beach Resort in the Bahamas, and Ripley’s Believe It or Not in Newport, Oregon are also part if the acquisition. The purchase price has not been disclosed. For continuity, the Oak Bay staff, including CEO Brook Castelsky, are expected to remain at their posts.

The Graham Clarke Group already owns Coal Harbour Marina and the Vancouver Harbour Flight Centre. In addition, the Group operates the three vessels of its 113-year-old Harbour Cruises in Vancouver, and Western Pacific Marine, which operates ferries in B.C.’s interior and the Lasqueti Island ferry. This latest acquisition reinforces its position as a premier marine and tourism operator in British Columbia.

Plans will be developed to revitalize Oak Bay Marina, including the installation of high-tech floats, after discussions with the Municipality of Oak Bay and local First Nations.

The post The Graham Clarke Group Has Acquired the Oak Bay Marine Group’s Four Marinas appeared first on Pacific Yachting.

Ghost Town of Anyox 12 Feb 2025, 5:33 pm

Located in northern British Columbia, on the shores of Granby Bay in Observatory Inlet, lies Canada’s largest ghost town—Anyox. This remote area is about 130 miles north of Prince Rupert and is only approachable by boat, float plane or helicopter.

Located in northern British Columbia, on the shores of Granby Bay in Observatory Inlet, lies Canada’s largest ghost town—Anyox. This remote area is about 130 miles north of Prince Rupert and is only approachable by boat, float plane or helicopter.

The story goes, that around 1910, Granby Consolidated Mining, Smelting and Power Company (known as Granby Consolidated) started buying up land in this area and began constructing the town in 1912. Anyox was a booming town until 1936, best known for its mining operations of copper and other precious metals. The town was built to accommodate mine workers and their families and the town’s population reached over 2,500 at its peak.

There were no roads or railways linking Anyox to the rest of BC, and all connections were made by ocean steamers travelling to Prince Rupert or Vancouver. This lack of connection to the outside world meant Anyox was self-sufficient and the town boasted amenities such as machine shops, a curling rink, a tennis court, a golf course and a hospital. In 1918, an incoming ship brought the Spanish flu to Anyox and dozens of residents died in the epidemic. In the early 1920s, John Eastwood, a dam engineer, designed a hydroelectric dam for the area. Once constructed, it reached 156 feet high and was the tallest dam in Canada at the time.

The fate of the small town began to turn. The Great Depression brought hard times and the beginning of the end for Anyox, when the demand for copper went down. The mine shut down in 1935 and the town was eventually abandoned. Salvage operations in the 1940s removed most of the machinery and steel from the town and then two forest fires, in 1942 and 1943, wiped out most of the wooden structures. What are still visible are the remains of the Anyox Auxiliary Secondary Steam Plant, Hydroelectric Power Plant, a cemetery and other abandoned structures and machinery, which have been recaptured by nature and overgrown with foliage.

The closest marina is in Prince Rupert. To get to the shores of Anyox, travel to west side of Observatory Inlet at Granby Bay, At the Mouth of Hidden Creek, in Cassiar Land District at 55°25’00”N, 129°49’00”W.

Main hydroelectric power plant in Anyox, British Columbia, Canada. This photograph shows the main power plant for the mine. with Falls Creek and Granby Bay in the background.

Main hydroelectric power plant in Anyox, British Columbia, Canada. This photograph shows the main power plant for the mine. with Falls Creek and Granby Bay in the background.The post Ghost Town of Anyox appeared first on Pacific Yachting.

When the Anchor Drags 12 Feb 2025, 12:40 am

We all dream of placid waters when at anchor.

We all dream of placid waters when at anchor.If you cruise long enough, the day (or night) will come when you will have to deal with your anchor dragging. It may be just a minor inconvenience or an embarrassing situation witnessed by amused fellow boaters, but it could also be something far more serious: the loss of your boat or even a life. The causes for this potentially dangerous scenario are threefold: inadequate ground tackle improperly deployed; a poor holding bottom or unsuitable anchorage; or deteriorating weather conditions.

Let us examine each in turn so we will be better prepared when, not if, the anchor drags.

Proper Ground Tackle Unfortunately, many cruising folk, be they sailors or powerboaters, are not properly equipped for the conditions they are likely to encounter on an extended cruise. The excuses vary: “I don’t want excessive weight in the bows.” “I’m not strong enough to handle a big anchor.” “This is what the boat came with.” Or, “I can’t afford anything else.” Yes, anchors and anchor cable can be costly but they are one of the best investments you can make as a boater.

There are a lot of options available in the anchor marketplace so be careful when choosing yours. It is best to buy only bona fide products (not imitations) and ask fellow boaters what their experience has been with the type of anchor you’re interested in.

Anchor Types There are the old standbys like the C.Q.R. (plough) anchor, the Danforth and the Fisherman’s. Then there are the newer options like the Bruce, Delta and Rocna anchors. There are a few others which are essentially developments on the original plough anchor.

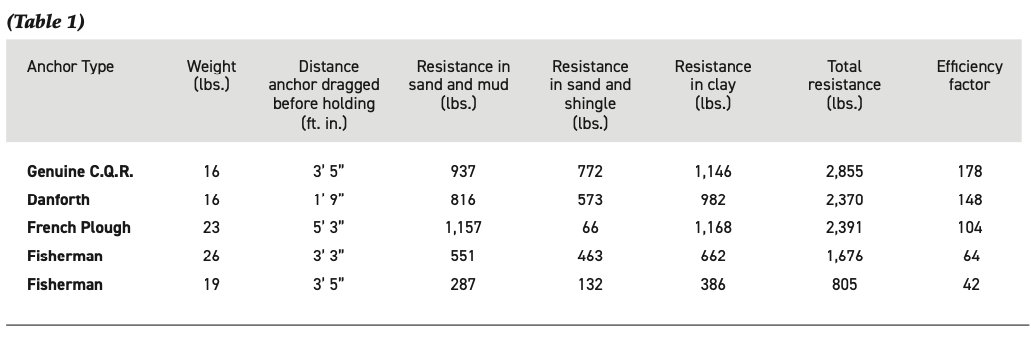

After the end of the Second World War, yachting took off and became the universal pastime we know it as today. It is instructive that during that time a French magazine undertook a test on the holding power of anchors available at the time in three types of bottom (Table 1). The efficiency factor of each anchor (shown in the right-hand column) was arrived at by dividing the total resistance in pounds by the weight of the anchor in pounds. It makes for an interesting comparison.

Anchors

CQR.

CQR.C.Q.R. The genuine C.Q.R. (secure) was invented by professor, later Sir, Geoffrey Taylor, and consists of a single fluke in the form of two ploughshares back to back. Itwas originally made by Simpson-Lawrence and is now available from Lewmar.

Danforth.

Danforth.Danforth The American-designed Danforth anchor has two pivoting flukes placed close together with the shank between them and the stock across the crown.

Fisherman.

Fisherman.Fisherman The Fisherman-style anchor was so popular with early yachtsmen that it is also called a yachtsman’s anchor. It is no longer as widely used as it once was and has the disadvantage of potentially fouling the anchor line on the exposed fluke if the wind or tide changes.

Delta.

Delta.

Rocna.

Rocna.

Bruce.

Bruce.Variants It seems that every year, someone invents a new anchor but the modern “plough” variants, like the Delta (also available from Lewmar), the Rocna and the Bruce (also called a “claw” anchor) have earned good reputations to rival that of their progenitor, the original C.Q.R. The important thing, as the table illustrates, is that you choose a proven design and that different anchors perform differently in varying types of bottoms.

A Poor Holding Bottom It is significant that, when tested, the French Plough had a resistance of 1,157 pounds in a bottom of sand and mud and only 66 pounds in a sand and shingle bottom. (Clay is an excellent bottom whereas fine, light sand is not.) Since we can’t always choose an ideal bottom it is best to carry two or three anchors of radically different types: a bower which is the main anchor, and a kedge about 2/3 the weight of the bower and, ideally, a second bower in case of an emergency. A light anchor, which can perform admirably in a mud bottom, may not be heavy enough to work down through a bed of eelgrass, for example, so what may be a poor holding bottom for one anchor may be fine for another.

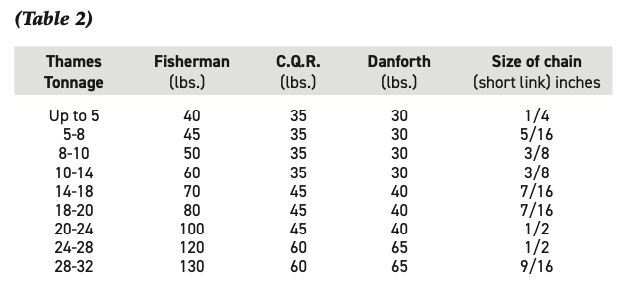

Anchor Weights The following table gives the approximate weights of bower anchors and sizes for chain for boats of different tonnages, and was developed by the late Eric Hiscock, who did a great deal to make boating a popular and practical pastime for the average person (Table 2). There is a lot of confusion about tonnage so be aware that Hiscock is applying Thames tonnage here which is not registered tonnage (such as appears on your vessel’s Certificate of Registry) or displacement tonnage (which is your vessel’s weight if put on a scale). Thames tonnage can be computed as follows:

(L.B.P. – Beam) x Beam x 1/2 Beam (all in feet)

94

L.B.P. is the Length Between Perpendiculars measured on deck from the fore side of the stem to the after side of the stern-post (on which the rudder is hung), and does not include a counter or canoe stern. It follows, for example, that a little traditional yacht like the Contessa 26 will come in at just under 6 tons TM, a Catalina 30 at 10 tons TM and a 39-foot Nordic Tug at 25 tons TM, approximately.

Hiscock was also of the opinion that it was unwise to use any type of patent anchor weighing less than 30 pounds, for although it may well have sufficient holding power when dug in, it may not be heavy enough to force its way through a layer of weeds. Since the C.Q.R. is not made in a 30-pound model this will explain the discrepancy between it and the Danforth in the table.

Deteriorating Weather Conditions If we have chosen our anchorage wisely (not too deep and well protected from wind and waves), paid out at least seven times the depth at high tide in chain and employed an adequately sized anchor, properly set in good holding, then we have taken reasonable precautions against dragging. Unfortunately, if it really starts to blow we might still get into trouble.

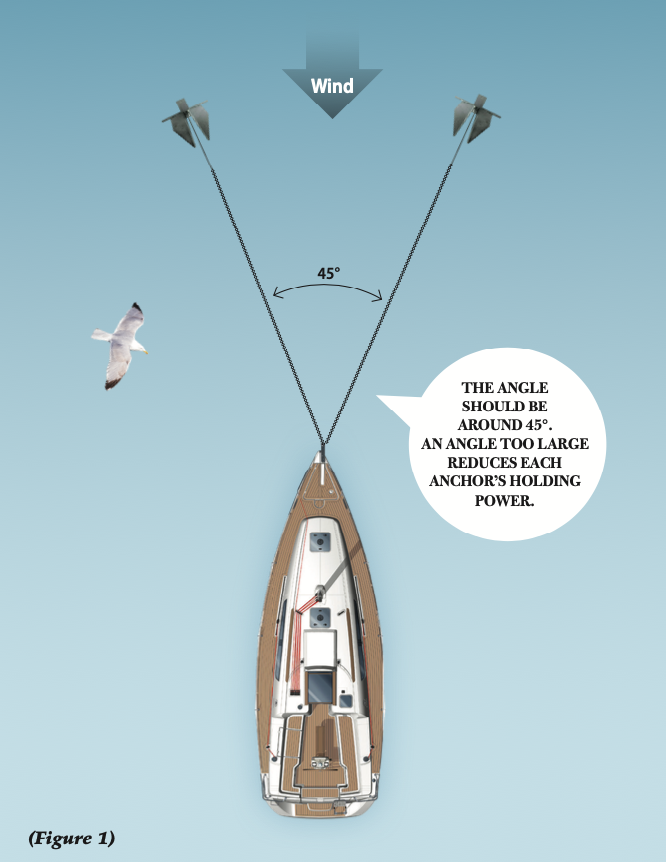

Given sufficient room in an anchorage, the first and simplest answer to severe weather is to veer more anchor rode. This not only keeps the chain as horizontal as possible but also reduces the stress caused by jerking on the anchor as the yacht sheers about in the squalls. Unfortunately, most anchorages, especially the good ones, are a little too crowded to permit you to pay out as much rode as you would like. Now is the time to deploy the second bower (Figure 1) or the kedge, but this takes a lot more work and careful judgement than simply letting out more line. The trick is not to make the angle formed by the two anchors and the bow of your boat too large; if it is, you effectively reduce the holding power of each anchor. Old sailors knew this as the “swigging effect” and it is what allowed them to crank a heavy sail up the last few inches to get a taut luff. The halyard would be belayed and then a couple of deckhands would pull out and down to sweat up the sail. It is similar to pulling the string when notching an arrow on a powerful bow. When deploying the second anchor, therefore, motor up until you are abreast and to one side of where you lowered the first anchor. Ideally you should drop the second anchor so that the angle at the bows between both cables is not more than 45 degrees when the yacht settles back on them. Easier said than done in a strong wind, but if the angle is too great you exert more force on your anchors than you should.Another weapon in the anchor-dragging arsenal is a “messenger” or “killick.” This is a weight which can be added to an anchor line some distance behind the anchor to keep the pull on the line as horizontal as possible. Almost anything will do if it’s heavy enough—a sash weight, a big trolling lead, a piece of trim ballast—but this ruse is pulled off far more easily in a yacht of modest size.

The Last Resort Still dragging? Start the engine and put it in gear ahead. I once rode out a notorious “Papagayo” wind in an anchorage in Costa Rica aboard the training schooner Pacific Swift with two large anchors (500 pounds and 350 pounds) deployed, 150 feet of heavy chain on each and the engine roaring almost full speed ahead. I had a third anchor ready to swing out from a tackle attached to the end of the lower yard (so as not to foul the other two) when dawn broke with sufficient light to pick my way out among the reefs.

“Never again,” I muttered, not for the last time!

The post When the Anchor Drags appeared first on Pacific Yachting.

Tumbo Island 28 Jan 2025, 12:09 am

At the southern tip of the Gulf Islands, overlooking the American border, lays Tumbo and Cabbage islands. The two islands attract all kinds of boaters due to the protected anchorage that lays between them, the backcountry camping sites and their proximity to Vancouver, Sidney and the American San Juans.

We approached Tumbo from the south. Our Tartan 42 barrelled down Boundary Pass under sail on a close reach in the localised thermal winds that were accentuated by the topography of Saturna Island’s rocky cliffs. We tacked between the freighters anchored in Boundary Pass, being careful to avoid the vessel no go zone to port. An orca sanctuary zone lies off the southern side of Saturna Island, off East Point and Narvaez Bay. We overheard the monitoring boat on channel 16 hailing another vessel that had entered this area meant to help protect the Southern Resident orcas. This was the first time I had navigated these waters since this no go zone had been enforced in 2019 and although we were keen to stay away from the area for the sake of the whales, in a poor attempt to reef sails with the quickly building wind, we danced closer to the edge of the line than I would have liked and it wasn’t long until I saw the monitoring vessel mirroring our every move. We reduced sail area and fell off the wind once more, thankfully avoiding the scolding of the monitor boat.

The afternoon winds were building and the tide was about to switch to a flood, so we were anxious to cross the bar that lies to the south of Tumbo Island—known to create some messy chop when wind and current are opposed. Summer in the Gulf Islands can be busy, channels and sounds becoming highways to tourists and locals alike, both enjoying some of the best cruising grounds on the British Columbia coastline. In an attempt to find our own bit of solitude after the previous night’s hectic (albeit enjoyable) stay in Montague Harbour, we decided to drop our hook on the northeast side of Tumbo—an open anchorage that is noted as a day use anchorage in Navionics and most guidebooks, as it is exposed to summer winds and freighter wake. The summer high pressure system had been consistent and the forecast didn’t indicate anything different. We decided to take our chances for the night and dropped our hook in about 40 feet in shingle bottom.

Another sailboat shared the large anchorage with us, but by late afternoon they had pulled up anchor, leaving us to swing on the hook by ourselves. A slight swell had us bobbing in the bay and the wind went light by mid-afternoon. With the weather settled and the anchor hooked, we hopped in the dinghy and headed to the rocky shoreline to explore and stretch our sailor legs. A rope swing lured us toward the trailhead and we plodded along the north side of the island, enjoying the scenes. Three small wood buildings, with windows boarded, gave us an insight into the rich history of the island. Now owned and managed by Parks Canada as part of the Gulf Islands National Park Reserve, Tumbo was once a homestead, a coal mine, and even a mink farm in the 1920s.

Wafts of rosemary filled our noses and long golden grass tickled our ankles as we continued through the old orchard. From a previous visit in October, I recognized the orchard trees to be Quince, which provide plenty of golden fruit come autumn. A wetland runs through the centre of the island where dozens of Canadian Geese had made themselves at home. We reached the west side of the island overlooking the protected anchorage, Reef Harbour, and found shade under a beautiful Garry oak tree. The anchorage was a joyous sight, full of people enjoying the summer afternoon. Reef Harbour is a great option for visiting boaters, with 10 moorings that get snagged quickly on weekends in summer months. It’s easy to see why as there is a beautiful sandy beach that welcomes kayakers, campers and picnickers. Moorings are $14 a night (self-pay) during the summer and there is plenty of room for anchoring in good holding, too. The harbour is well protected from the southeast winds, but open to the northwest. The activity at Cabbage Island looked like fun, but we were happy to remain onlookers and we retreated back to our peaceful bay after a short rest.

The barbecue was calling and our stomachs were rumbling, so we wandered off in the direction of the boat. Footloose sat calmly at anchor; picturesque Mount Baker looming in the background. Evening fell upon us and the Olympic Mountains seemed to be getting closer as the light faded. The sunset was just as impressive that calm summer evening. The colours came in seemingly never-ending cycles, finally fading from a deep orangey brown to the inky sky that was soon to be full of stars, blanketing us for the night. A slight roll from the exposed strait had us drifting off to sleep and an occasional freighter passing during the night reminded us of our exposed location. But the next morning dawned to a beautiful Gulf Island sunrise and we were grateful to have gotten to spend a night at this special spot.

When You Go

Coordinates: 48 47.751’N, 123 03.671’W

Nearest Marina: Port Browning, 250-629-3493

Cabbage Island Campground Info:

Accessible by water only

Five primitive campsites

No designated tent pads, please setup your camp in a low impact area. Practice leave no trace principles

Compost toilets

No potable water

Food cache

Orca Sanctuary Zones

Southern Resident killer whales have been considered endangered species since 2005 and it is vital they are protected for their long-term survival to be ensured. In an effort to help protect these whales from accidental collisions and to allow them access to their favourite feeding grounds, orca sanctuaries, officially called Interim Sanctuary Zones (ISZ), were established in 2019. These ISZs are in effect from June 1 to November 30. No vessels are allowed inside these areas during that time period.

For more information, visit pac.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/fm-gp/mammals-mammiferes/whales-baleines/srkw-measures-mesures-ers-eng.html

The post Tumbo Island appeared first on Pacific Yachting.

Deck Repairs 27 Jan 2025, 12:15 pm

When we joined the Barnet Sailing Co-op last year we were thrilled with the idea of going from one couple owning one boat, to being part of a team of 70ish people who share the upkeep of a matched set of six Catalina 27s. Many hands make for light work as they say. Though I’m pretty sure the person who said that never took part in late winter haulout… Still, the benefit of taking care of a fleet is that if one boat has a maintenance issue, chances are the other boats do too. And by the time you’ve made the same repair two or three times, you’re practically an expert.

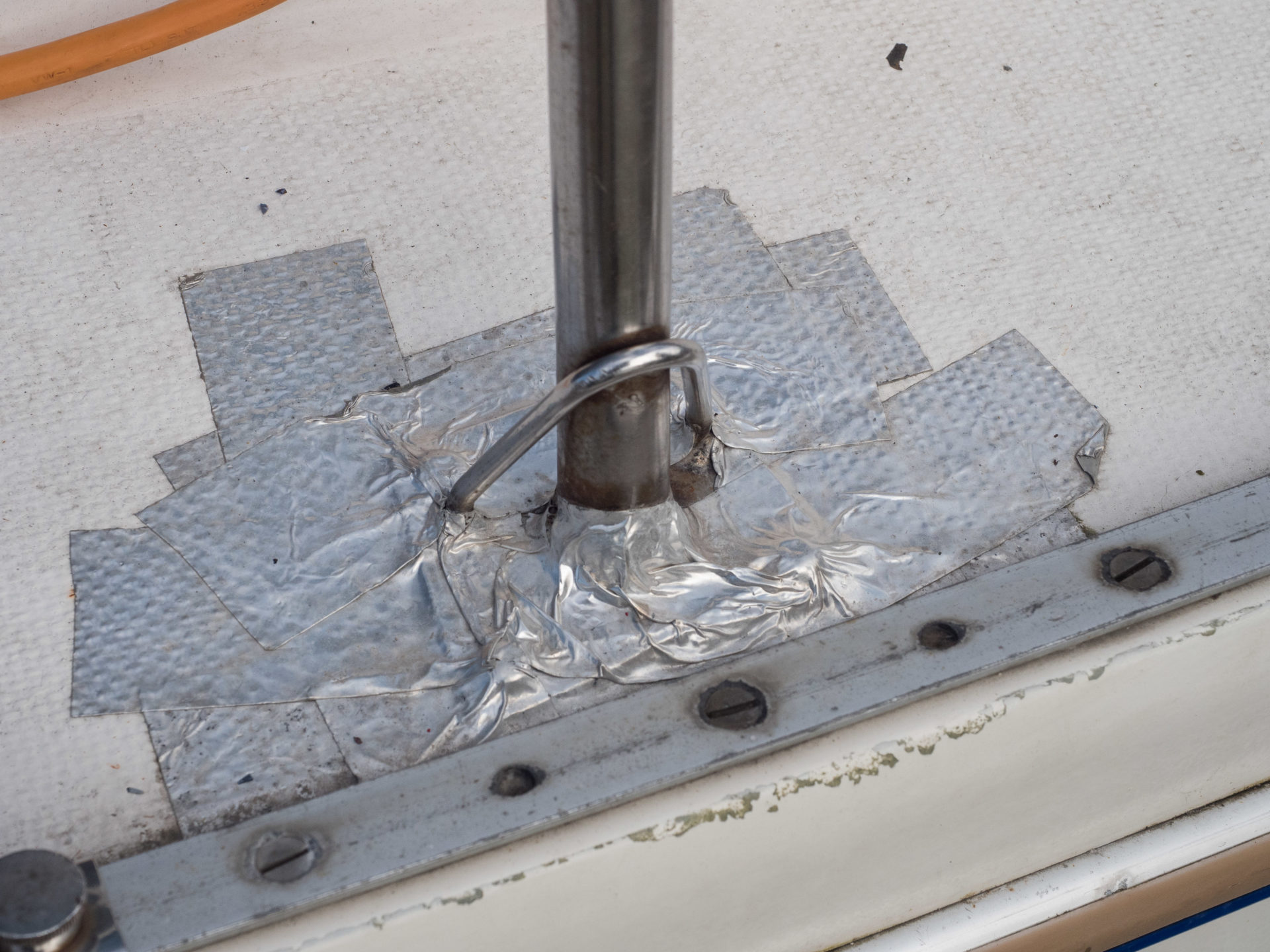

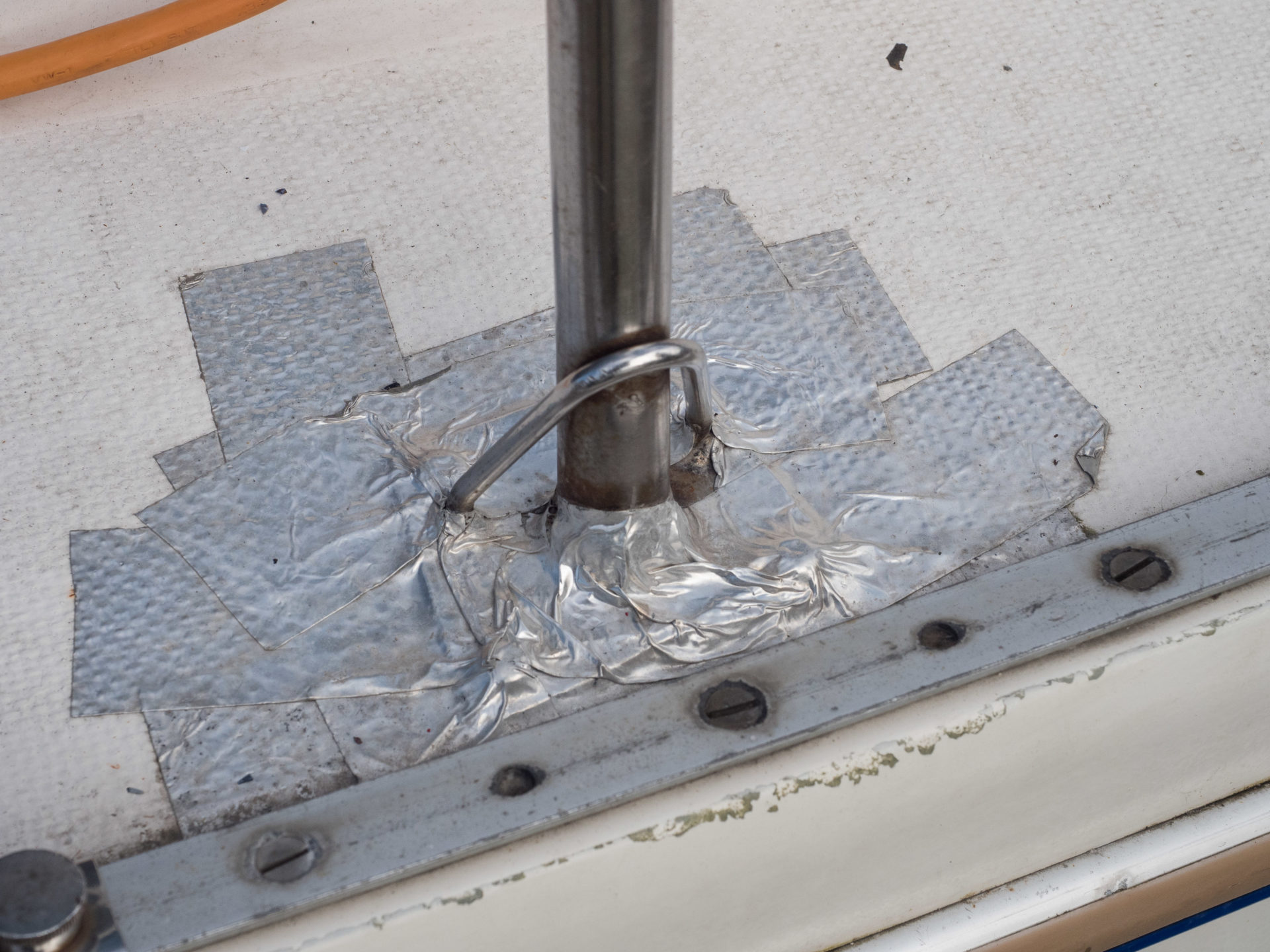

This is why I wasn’t worried when I saw the aluminum foil tape on the base of one of SV Honeybee’s stanchions. Although the “water leak” note (written inside, beneath the stanchion) seemed to concern one of our newbie co-owners, we were able to reassure him that deck repairs are typically quite straightforward.

The thing is: boats leak. They are large, flexible structures that experience considerable stresses and loads. Most of these loads occur at the points where hardware is attached to the deck. As time goes on, the sealant compound used to bed the hardware loses flexibility and breaks down, then the deck flexes just enough to break the seal and one day you may find yourself pulling out a roll of tape just to keep things dry until you can make the fix.

Stopping the water quickly, even if it means you’re stuck with cleaning up tape residue (duct, gorilla or foil tape will all work), helps keep the water from breaching the top skin of the fibreglass. Once this happens, it travels the path of least resistance. In some cases this means it goes straight through, but with improperly prepared holes the water can travel along the core (turning it into a soggy mess), then it take a detour through the interior liner before it makes a random appearance inside the cabin.

The leaking stanchion on Honeybee was discovered after a heavy winter rain. The leak isn’t a cause for concern—it’s easily repaired.

The leaking stanchion on Honeybee was discovered after a heavy winter rain. The leak isn’t a cause for concern—it’s easily repaired.

As we cleaned up the area we discovered old holes which had never been properly repaired. Also the new holes that were drilled through the deck left the core exposed.

As we cleaned up the area we discovered old holes which had never been properly repaired. Also the new holes that were drilled through the deck left the core exposed.

Make sure the bolt threads are well covered.

Make sure the bolt threads are well covered.

Keep in mind that when you tighten the bolts you don’t want to squeeze out all the sealant. Instead tighten until just snug. When the sealant cures you can give the bolts another quarter turn to compress the sealant and make a better seal.

Keep in mind that when you tighten the bolts you don’t want to squeeze out all the sealant. Instead tighten until just snug. When the sealant cures you can give the bolts another quarter turn to compress the sealant and make a better seal.Read on for common deck issues and their fixes.

Stanchion bases and Deck Hardware

Every time a guest heaves himself up onto your deck using your stanchion for leverage, he’s increasing the possibility that the deck where it is attached will spring a leak. Stanchions and pulpits bases are often undersized or have inadequate backing plates for the work we ask them to do. But even cleats, sail tracks and dodger bases may start to leak over time as the caulking deteriorates.

The Fix

If you’re lucky, your boat was constructed so that the deck hardware was attached to solid fiberglass and not a cored deck. If this is the case, you’ll just need to clean out the old bedding compound and redo it with fresh sealant. To help make fasteners more leak proof, you can countersink the holes. This leaves space for some additional caulking to form an O-ring of sealant around the fastener that won’t be squeezed out when you bolt down the hardware.

An important additional step is to include a backing plate if there isn’t one. The backing plate helps distribute the forces. Plates can easily be made of aluminum, stainless steel or fibreglass, but avoid plywood because it can compress or rot.

Pre-existing Holes

Many boats have holes that someone drilled in the deck for one purpose or another and never repaired properly. Often they are filled with putty or caulking, which over time cracks and loosens. These holes may be quite obvious or they might be hidden under deck hardware. Either way they can start leaking over time.

The Fix

The first step is again to dig out all the old caulking. If the deck is cored you need to redrill a slightly larger hole to expose new deck material. Check the core to make sure it is dry. If there is dampness, dig out that core material from between the upper and lower fiberglass skins until you reach dry material. Clean the area with acetone then tape off the bottom of the hole. Slowly fill the hole with epoxy thickened with colloidal silica. Apply a dot of paint on the cured resin to match the gelcoat colour as best you can. Keep in mind those gelcoat repair kits aren’t much good for this application; gelcoat doesn’t stick well to cured epoxy.

A leaking vent fitting turned out to have exposed core. Before resealing it we dug out the core and sealed it with epoxy. Don’t skip a step and set your fitting into this uncured epoxy: if it ends up leaking, or if the fitting needs replacing it will be almost impossible to remove. Instead let the epoxy cure and then reinstall the fitting with sealant.

A leaking vent fitting turned out to have exposed core. Before resealing it we dug out the core and sealed it with epoxy. Don’t skip a step and set your fitting into this uncured epoxy: if it ends up leaking, or if the fitting needs replacing it will be almost impossible to remove. Instead let the epoxy cure and then reinstall the fitting with sealant.Hatches, Windows and Ports

Hatches, windows and ports often begin to leak over time. Before you look for other causes of leaks, first check the gasket. If the gasket is old or damaged it won’t compress and seal and you may have found the leak source. Also check any hatch dogs or hinges that go through the lens. Some dogs have O-rings that allow the dog to rotate and these O-rings need regular lubricating with silicone grease.

If once you’ve serviced the gasket and O-rings, you still have a leak; it’s probably safe to assume the caulking/bedding is too old and it’s time to rebed the hatch. The least likely reason for a leak is the caulking that holds the hatch pane in place has failed. This is usually an obvious leak to find.

The Fix

If water is leaking in from around the hatch or window frame, you’ll need to unbolt the entire assembly. Next, scrape off the old caulking from the deck and frame. Use an oversized drill and drill out the fastener holes. Make sure the core has been sealed with thickened epoxy. If unsealed core is visible, dig it out to a depth of 10mm and fill the space with thickened epoxy. Be sure to fill the bolt or screw holes with epoxy too. When the epoxy is set, set the hatch or port in place and drill for the fasteners.

Caulk the hatch and deck with a generous amount of caulking after taping off the surrounding deck. Set the hatch or port in place and bolt it down without fully tightening the bolts. Only after the caulking has set and formed a waterproof gasket, should you tighten the bolts fully.

How quickly you need to find and fix a leak is a matter that is up for debate. Some boaters claim that boats leak and that you can never get ahead of the problem. In contrast, some surveyors tend to treat each leak as a catastrophe in the making. The truth probably lies between these two scenarios. With both of our boats we quickly tired of leaks and now with our club boats we believe in methodically working our way through all the deck hardware, hatches and ports—drilling, filling and rebedding. It takes time and effort but it doesn’t take long to become an expert. And by lessening the stream of water that invades your boat’s interior you’ll make boating more fun.

TIPS

-Don’t apply new caulking around a leaking fitting. It seldom works. Remove the fitting, and use new caulking.

-When possible use nuts and bolts and not screws. Screws are more difficult to get a good leak proof seal with and are not as strong as nuts and bolts for holding down hardware.

Caulking

Silicones Many people avoid silicone because it can contaminate future paint jobs. But it’s a good choice for plastics that are not compatible with other caulkings. Dow Corning 795 is a high strength adhesive silicone that should only be used to bond on plastic windows.

Polysulphide One of the most versatile and longest lasting of the caulkings. It can be sanded and painted after it is cured, but don’t use it with plastics. 3M 101 or “Lifecaulk” are common brands.

Polyurethane Avoid use on plastics because it will melt ABS and Lexan. 3M makes a few well known types such as 5200. It forms a very tenacious bond and is used by boat builders to attach the deck to the hull. The strength of the bond means it should be avoided for most deck hardware because when it begins to leak it will be very difficult to remove the hardware. 4200 is more caulking than adhesive and is a better choice for most hardware. Both of these come in normal cure and “fast cure” varieties. The fast cure has a shorter life after opening but cures much faster.

Sikaflex

291 is an adhesive / caulking similar in strength and use to 3M 4200. 292 is a much higher strength adhesive like 5200 that can also be used as a caulking. Use it to attach something you never want to remove without lots of effort.

295 is the special purpose Sikaflex caulking used to bond plastic windows in place. It needs a special primer. Sikaflex 296 is similar in use to 295 but should only be used for mineral glass windows.

Polyether These newer sealants are weaker than polyurethanes but are very resistant to exposure. West Marine “Multi Caulk” or 3M 4000 UV Polyether sealant are representative brands of this type.

Butyl tape comes in a roll and never really cures, staying flexible and soft for years. It doesn’t have any strength so only use it on fittings where fasteners are doing all the work.

The post Deck Repairs appeared first on Pacific Yachting.